More than just a vase

Updated: 2011-10-23 08:04

By Zhang Kun (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Quality blue-and-white porcelain is much sought-after at art auctions, and it can bring in exorbitant bids. Zhang Kun looks at the appeal of the qinghua ci.

Apiece of Ming porcelain broke a world auction record on Oct 5 when the blue-and-white vase was sold for HK$168.7 million ($21.7 million) at Sotheby's Hong Kong.

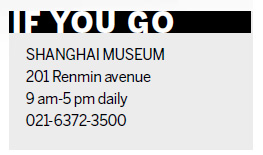

Fine imperial porcelain have long been among the most sought-after antiques, and the Shanghai Museum has placed priority on the collection of blue-and-white porcelain since day one. After decades of effort, a very systematic and credible collection can now be found at the museum.

One of its finest pieces, a flat jar decorated with camellias, dates back to the same period of the auctioned piece in Hong Kong. Both were made in the reign of the Emperor Yongle (1403-1424) of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

He was the third emperor of the dynasty and also the one who moved his capital from Nanjing to Beijing. Among his many achievements, he had the Forbidden City built within 14 years, and commissioned an encyclopedia which was named after him. Yongle was also the emperor who commissioned the eunuch admiral Zheng He on his voyages.

Thus, porcelain from the Yongle period are often larger pieces that show the influences of foreign culture. Dragons on the patterns are typically fierce-looking, reflecting the pioneering spirit of the time, according to Ma Weidu, antique collector, critic and owner of the private Guanfu Museum.

The camellia jar from the Shanghai Museum stands 25 cm high and 10 cm wide at the bottom. These jars, commonly known as baoyue ping, or moon-embracing jars, were not products of the pottery hub of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi or indeed of any other kiln in China.

"It is a foreign format, in Islamic style from West Asia. A small number has survived and is collected by the Percival and David Foundation, a few museums in Japan as well as the Palace museums in Beijing and Taipei," says Lu Minghua, a researcher with the Shanghai Museum.

The foreign element probably entered China with admiral Zheng He's voyages, a total of seven expeditions. These started in the third year of Yongle's reign and Zheng and his fleet went as far as the coasts of Africa.

"He could have brought back large collections of Persian patterns to the palace, which then had them made into porcelain," Ma has written in his series of books on antique ceramics.

Much trade was conducted between China and Middle-Eastern countries in the Yongle period, which largely enriched the creative pool of patterns for the blue-and-white porcelain.

"The flat jar at first sight, is not something commonly seen among Chinese porcelain, but shows the influence of Persian culture," Ma writes. Many were later shipped back to Southwest Asian markets by Muslim traders based in Guangzhou.

The blue of Yongle period porcelain is a lot brighter than blues of previous periods, and the underglaze is also much finer, Lu had written in Imperial Porcelain from the Ming Dynasty.

"People regard the reigns of Yongle and Xuande (1426-1435) as the golden age of Chinese blue-and-white porcelain. Pick up any piece from these periods at the Shanghai Museum and you are looking at a masterpiece," Lu says.

The blue in the best porcelain from these periods is a shade of sapphire, thanks to cobalt pigment imported from Persia since the 13th century. Cobalt was a precious commodity that was worth twice its weight in gold. Later, potters in Jingdezhen began to develop their own sources of cobalt.

Chinese collectors now have a keen interest in the imperial qinghua ci, and they are constantly breaking records at international art auctions. One reason is the quality of the genuine wares.

"Imperial porcelain from the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties were made under strict supervision," says Nicholas Chow, deputy chairman in Asia, and international head of Chinese ceramics and works of art at Sotheby's.

The record-breaking vase with fruit sprays that was recently sold was named meiping, or plum vase, mainly because of its tiny neck, making it impossible to hold anything else but a single stalk of plum blossoms.

You can contact the writer at zhangkun@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 10/23/2011 page15)