Memory of Flying Tigers honored

Updated: 2015-04-20 09:50

By Li Yang(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

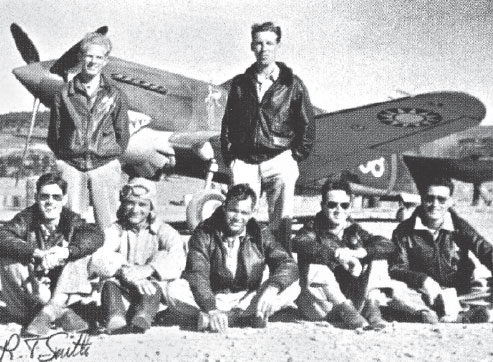

Members of the 1st American Volunteer Group, better known as the Flying Tigers, gather for a group photo at Zhijiang airport in Hunan province during World War II. [XINHUA] |

Thanks from far away

When he was 9, Long Fenggao, an 80-something retired policeman who attended the opening ceremony, spotted an injured US pilot in a rice paddy, and acted as a guide for villagers to carry the pilot to the cave command post at Yangtang airport. Whenever Flying Tiger pilots and families visit Guilin, Long always appears and greets them emotionally like old friends, often with tears in his eyes.

"All my family died in the Japanese bombings. The Flying Tigers helped me to take revenge. I regard their families as my own family," Long said. "I am honored to have helped save that injured US pilot, even though I don't know his name."

In the early 1950s, Long volunteered to fight in the Korean War but the cease-fire was signed before he was sent to the front. When asked about the difference between the US soldiers he greets so effusively in Guilin and the ones he would have fought on the Korean Peninsula, he responded seriously: "The US soldiers under President Roosevelt were good, the soldiers under President Truman were bad."

Another local resident, a reserved villager called Jiang Jun who lives deep in the mountains, was unable to attend the opening ceremony, but in 1996, he and his brother-in-law Pan Qibing discovered a crashed WWII-era B-24 bomber in the mountains that had been the Flying Tigers' home in China. The bomber, which had a crew of 10, hit the 2,000-meter-high Mao'er Mountain on the night of Aug 31, 1944, after bombing the Japanese fleet at Kaoshiung port in Taiwan.

Pan traveled to the US after the two men received a thank-you letter from then-President Bill Clinton for rescuing a US reporter who fell down a cliff while covering the retrieval operation. Jiang applied for the visa too. But he was turned down, and a US visa official told him: "What you have done is already history." Instead of traveling, Jiang stayed home to care for his sick, elderly mother.

In 2005, however, he was invited to a reception for the children of Flying Tiger pilots organized by the local government in his hometown. "I didn't know the old US pilot who embraced me so tightly, but we both shed tears. He said 'thank you' again and again," Jiang recalled. "I just smiled in return. I think that old man's hug was much better than the US president's thank you letter."

With the help of the FTHO and the local government, the project to build the museum started in 2007, but the complexity of receiving donations from overseas resulted in the construction work progressing intermittently for eight years.

The Chinese people's fight against the Japanese army and their sacrifices in WWII are largely unknown in the Western world. "Were it not for the Chinese battlefield, Japan would have sent more troops to fight the US in the Pacific," said Tom Palmer, a retired US Air Force pilot from Auburn, California, who was visiting the heritage park. "It is meaningful to have the park to tell young Americans and Chinese about the mutual assistance of the Chinese and American peoples."

As an 8-year-old, Herman Leong, a Hawaiian-born Chinese-American who is also known as Liang Riming, witnessed the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. He later served as a navigator in the US Air Force from 1956 to 1968.

"Although I am third-generation US-born, I am always concerned about the development of China," said Leong, who gave stirring renditions of the Chinese and US national anthems at the park's opening ceremony. "The Flying Tigers were my childhood heroes. Their experiences in China tell us that the two peoples share the same belief in peace. And we have so many common interests today. There is no reason for China and the US not to become good partners to safeguard world peace."

While visiting the newly opened museum, Jay Vinyard, a 93-year-old retired pilot who regularly flew the dangerous Hump route in the 1940s to deliver goods to occupied China, was asked about the lessons he had learned during the war. The elderly man looked thoughtful for a while, and then replied: "In war, luck is your best asset."

Today's Top News

Britain celebrates Queen Elizabeth II 's 89th birthday

Cuban FM visits France over relations

Auschwitz bookkeeper goes on trial in Germany

Russia willing to restore relations with Kiev: Putin

Asian markets jumpstart UK car industry

Smog magnifies staffing woes for EU firms

Silk Road initiatives to connect people's hearts

AIIB to operate in 'transparent way'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|