Culture vultures swoop across the plateau

Updated: 2014-06-27 08:09

By Hu Yongqi and Da Qiong

|

|||||||||||

|

Young people perform the ralpa dance in Qamdo prefecture in the Tibet autonomous region. The dance is one of eight national-level intangible heritage items in the region. Provided to china Daily |

Central and local governments are pouring money and expertise into the protection and preservation of traditional art forms in the Tibet autonomous region, as Hu Yongqi reports from Qamdo, and Da Qiong from Lhasa.

Even though night had already descended on Beijing, at 9 pm on a summer evening the sun was still shining over the plateau of the Tibet autonomous region. In Qamdo prefecture, the largest city in the east of the region, a huge screen in Liberation Square played traditional music to more than 1,000 people who formed a number of concentric circles and began a traditional dance.

As the dance, known as the gordro, progressed, some people left the circle, only to be replaced by others. Age was irrelevant, young and old enjoyed the simple pleasure of dancing together. Tourists took photos to record this distinctive local custom, which the locals perform every day, even during rainstorms. Nothing dampens their enthusiasm.

However, for many years, people in overcrowded Qamdo were unable to find an open space to practice the dance, so they crowded around the fire pits to entertain themselves by having a few drinks and singing.

Then, in 2012, the prefectural government built a 1-hectare square to accommodate the dancers, and this simple art form was revived with increasing vitality among the locals and tourists.

Gordro dancer Nyima Tsering walked among the crowd, ready to provide guidance to anyone in need. When the city began a reconstruction project two years ago, Nyima Tsering and his troupe took turns leading the dancing in the square every night, which contributed greatly to the popularity of the traditional art form.

"The dance is easy to learn and doesn't really matter where it's performed. It won't die as long as we can maintain the very essence of grassroots art, which is to get people involved," said the 36-year-old.

Last year, the central government added eight of Qamdo's local art forms, including the gordro dance, performances on a six-stringed lute-like instrument called a biwang, which is also the name of a local dance, and specialized techniques such as those used in the extraction of salt, to a list of programs to protect "intangible culture" - expressions of culture passed down from generation to generation. The regional government listed a further 15.

In the past five years, the prefecture has spent 2.6 million yuan ($418,000) promoting the local cultural heritage, according to the Qamdo Administration of Culture.

In Tibet, more than 1,000 forms of intangible culture now receive dedicated support from the local and central governments, and local authorities have conducted a comprehensive survey to record many aspects of the local culture, some of which have almost disappeared. The regional government also took a range of measures, such as increasing the subsidies paid to "inheritors" - people whose family members have passed down their knowledge, and are paid to maintain the traditional arts - to encourage a revival of indigenous culture among the younger generation.

Growing popularity

Gordro, which originated among farmers and herders, consists of two parts, the song and the dance itself, and its form differs from place to place. For example, in the herdsmen-dominated Nagchu prefecture, one sees a different style, more relaxed, yet wilder.

The dancers hold hands and form a circle. The music begins slowly, but the tempo increases and the dancers gather speed until they end the song with a frenzied shout of "Ya!" The dance doesn't require much technical ability and the moves are easy, factors that have greatly increased its popularity.

Two other local dances, including the biwang, which originated in Mangkam county, have also been taken under the wing of the national intangible culture protection system.

Yang Pei, who has a Han father and a Tibetan mother, learned the biwang from his grandfather. He often visits Liberation Square to help newcomers, gently correcting the movements of the uninitiated, especially tourists.

When Yang was a child, his family danced at home or in the cowshed. They only ventured into the fields to dance during the autumn harvest season. During one of these harvests, Yang began to imitate his grandfather's steps and learned the dance.

"At that time, kids could learn the moves, but weren't allowed to join the circle. However, Tibetans are born to dance and sing, unlike many people in China who work really hard but rarely have time to entertain themselves," Yang said with a giggle. "Later, we kids organized our own circle to 'compete' with the grownups."

When Yang was 18, he decided to become a professional dancer, but six years spent wandering around Lhasa, the capital of the autonomous region, wore away his ambitions and his desire to live in the city. So he returned to Qamdo in 2000, and became the lead performer of the 24-member Sanjiang Tea and Horse Arts Troupe, which performs at schools and in villages.

Nyima Tsering also takes his troupe to remote villages. "Our show targets farmers who rarely come to the town for entertainment because of their heavy workload," he said.

Visiting remote villages can be an arduous task because the winding mountain roads make travel laborious. However, sometimes there are no roads at all, so the performers walk, laden with their stage props, costumes and food. Despite this, they always remember to smile during their shows. Some of the more-outgoing farmers join in with the dances, even though their moves rarely match those of the professionals. Nyima Tsering said the ultimate purpose is to make people happy: "It doesn't matter how well people dance. It means a lot that they enjoy our show."

Facilities nowadays are far better than before. "Tibetans are known for their piercing voices, so we didn't use microphones because the quality was poor. Now, though, the audio systems and mics are much better, and our job is to compose and record new melodies for the gordro," he said.

The biwang dance encompasses 131 melodies, which the performers learn by heart, but because only a few of them are able to read sheet music, most find it impossible to compose new tunes.

That difficulty was underscored by Sonam Drolma, an inheritor of the ralpa dance which is also native to Qamdo. She said the dance has been boosted by a 1,000-capacity performing arts center built in the prefecture last year, but the difficulty in finding new material has affected her too.

"The dance can relieve pressure and stress. It won't be difficult to keep this art form alive, but the cultural atmosphere seems to be losing power because an increasing number of young people have moved away to study and don't have time to learn. The government should be doing more," she said.

Recording history

On June 1, as a way of strengthening the protection of indigenous cultures, the regional government implemented a version of the Law on Intangible Cultural Heritages, which has been tailored to suit conditions on the plateau.

The regulation stipulates that governments at prefecture and county levels must cultivate young talent and provide adequate financial support to preserve traditional art forms, especially those listed as intangible cultural heritages.

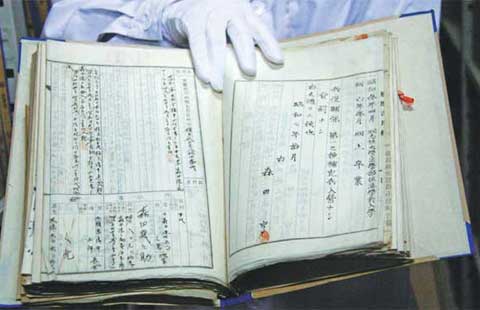

Since 2006, more than 3,000 officials in the region have been collecting information about all the listed intangible heritages. To date, they have collected about 100,000 transcripts and made 2,000 recordings of traditional music, dances and techniques, said Ren Shuqiong, deputy director of the Department of Culture of Tibet.

By the end of May, 120 million yuan had been spent on the protection of intangible culture, with the central government providing 90 million yuan of the total, she said.

Last week, 123 people were accredited as inheritors of intangible cultures at the Norbulingka Palace in Lhasa. Pema Dawa, a 40-something painter, was endorsed as an inheritor of Chentse-style Thangka, paintings on cotton or silk with a Buddhist theme. He said he was delighted to see the government paying more attention to the preservation of traditional art forms such as his, which dates back to the mid-15th century.

"Chentse-style Thangka has been influenced by both Nepali and Han culture," he said. "It means a lot for ethnic unity nationwide, and artists from both groups can interact to discuss techniques and artistic connections."

According to Ji Ji, director of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office of the culture department, the annual subsidy available to a national-level inheritor was raised to 10,000 yuan from 8,000 yuan in 2012, and the subsidy for local-level inheritors rose by 60 percent to 5,000 yuan per annum.

Opera 'rock stars'

In 2009, Tibetan opera, an ancient art form that developed over many centuries, was added to UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Performances combine folk dancing, singing and vocal dynamics. Hailed by cultural experts as a "living example of traditional Tibetan culture", the opera boasts a history of more than 600 years - about 400 years longer than China's national treasure, the Peking Opera.

In the past five years, the regional government has subsidized about 120 Tibetan opera troupes. Annual opera competitions are held to counter the decline in popularity of the form among young people, many of whom are losing touch with traditional culture because they live and work in other parts of China.

"Our department publishes the rankings, and the county officials see it as a way of enriching the local people's lives. County governments are encouraged to help the performers by providing funds to buy costumes and pay for rehearsal spaces. Hopefully, that will result in Tibetan opera attracting more local support," said Ji.

The department has also decreed that one-third of each troupe must be composed of performers younger than 40, according to Ji. "If not, we don't allow the troupe to participate in the contest. In this way, we hope young people will learn, and take leading roles in the future," she said, adding that the department has sponsored 32 training centers for local art forms and has provided a fund of 2 million yuan to refurbish living quarters and rehearsal facilities.

Ngawang Tenzin, deputy chief of the Center for the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Lhasa, said traditional art forms are being preserved to allow the younger generation to understand more about the cultures their ancestors created and preserved for hundreds of years.

He said the center hosts cultural exhibitions, featuring ethnic costumes, makeup and dancing, every day. In addition, the center arranges performances at schools, and selects talented students to study opera, dance and other local art forms.

Fans of the form treat the performers like rock stars. On May 21, Yang and his troupe visited Qamdo No 1 Middle School. The male dancers accessorized their costumes with knives, while the women wore elaborate jewelry. After carefully applying their makeup for two hours, the dancers appeared on a makeshift stage erected on the school's soccer field.

More than 600 students sat on the lawn and cheered. About 15 minutes after the performance began, classes ended and even more students rushed to the field.

No one spoke. Everyone watched Yang and his colleagues patiently. Some of the students had brought milk and snacks, but ate and drank in silence. When the show was over, the performers were given a standing ovation, and some students lingered to ask Yang for his autograph, which he duly wrote on their uniforms.

"Yang is a celebrity in Qamdo, and we are so happy to see him in person, instead on TV," said 15-year-old Sonam. "If possible, I hope he will come and perform for us every semester."

Contact the authors at huyongqi@chinadaily.com.cn and daqiong@chinadaily.com.cn

Palden Nyima contributed to this story.

Today's Top News

Prime London properties lure investors

FIFA bans Suarez for 4 months

Tycoon criticized for charity in NY

50 trapped Chinese back to Baghdad

Northern Iraqis flee their home, avoiding Sunni millitans

DPRK test-fires newly developed missiles

RIMPAC drill not window-dressing for China-US ties

Li puts China-UK ties on new level

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|