Closest ear won't always be the best organ for advice

Updated: 2013-11-04 08:10

By Cecily Liu in London (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

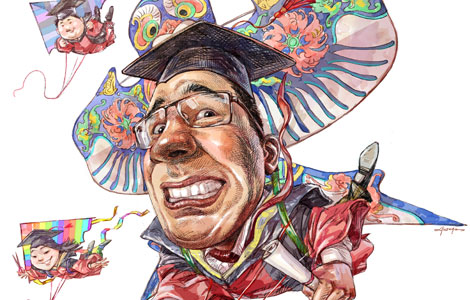

Jochum Haakma says receiving good advice has become a central issue as China has undergone a dramatic shift from being a receiver of foreign direct investment to become a keen investor overseas, especially in Europe. Cecily Liu / China Daily |

Business consultant warns of expensive mistakes in acquiring other companies

Who would you go to for advice if you were preparing to do a big business deal? Many Westerners, even with bread-and-butter issues such as buying houses and planning their retirement, would engage a financial adviser.

But for many Chinese, it seems, the go-to person, even with multimillion dollar transactions, is not a professional adviser but their spouse, their parents or some other relative, or friends.

That is the experience of Jochum Haakma, global director of business development at Dutch consultancy TMF Group. With company acquisitions, he says, he has seen many Chinese companies wanting to obtain advice from overseas friends and family instead of professionals.

"Say they have an uncle in Ludwigshafen who works in a Chinese restaurant. They trust this guy because it is his uncle, it's family. So they go with quite a complicated investment through this guy."

|

More often than not, the business decisions made under such circumstances are not the best. More money is spent on correcting mistakes, he says.

Receiving good advice has become a central issue as China has undergone a dramatic shift from being a receiver of foreign direct investment to a keen investor overseas over the past decade.

Haakma, who is also chairman of the China Chamber at Netherlands Council for Trade Promotion, says such a shift reflects China's attempt to move up the production value chain.

"Since China joined the World Trade Organization, it has become more open to the world and become a very interesting investment destination. And now you see the wave coming the other way."

A recent phenomenon in Europe is a surge of Chinese acquisitions, attracted by technology and know-how of the European targets, particularly in the manufacturing sector, he says.

In these cases it is common for the Chinese companies to take either full or part control of the target companies and retain the previous management to run the European operations, he says.

"The next step for these companies is to build factories in China, leveraging on the new technologies acquired."

For example, SAIC Motor Corp bought the British carmaker MG Motor UK in 2006 and then the Shanghai company resumed making MG cars in China for both its domestic and UK markets. Similarly, Zhejiang Geely bought the Swedish carmaker Volvo and Sany Heavy Industry bought Putzmeister, a German company that makes high-tech concrete pumps.

Chinese acquisitions in Europe last year were worth $10.566 billion compared with $259 million 10 years earlier. There were 78 Chinese multimillion-dollar deals in Europe last year compared with just 11 in 2010, investment platform Dealogic says. But Haakma believes there is a long way to go before Chinese companies become totally competent in choosing and securing the best acquisition deals abroad. One common mistake is being reluctant to hire local advisers.

"Most Chinese companies are not used to paying up front for consultancies," he says.

While he says he cannot stress enough the importance of obtaining good advice from the beginning, he understands why Chinese companies tend to make this mistake.

"I've seen in China that if you are an adviser, you don't get money. You get money in the tail of the deal, whenever successful. But in Europe and the US, sometimes the advisers won't talk to you unless you pay them first."

Haakma believes European advisers may have been too rigid sometimes and perhaps it would be good for them to take into account cultural differences, so to "talk more, wine and dine and maybe drink some Moutai (famed Chinese liquor) to get some trust first".

He is also noticing an increasing number of Chinese companies becoming more accustomed to the Western model of partnerships with advisers, perhaps as a result of an increasing number of employees having an overseas education.

Europe has become a particularly good location for Chinese acquisitions since the financial crisis and the eurozone crisis, when many well-performing companies suddenly experienced a shortfall of capital, he says.

"It is very difficult for them to get money from the banks. Some of them are willing to be taken over so long as the management is good. As for some second- or third-generation family businesses," he says, pointing to his neck, "the water is up to here".

It is often difficult to seek out such opportunities because the pride and dignity of family businesses make them reluctant to speak about financial difficulties.

To succeed, investors must demonstrate that they share the owners' vision for expanding the businesses, he says.

"It is not that you can publicize a list (of potential targets) because companies will not cry out loud that 'I'm almost bankrupt'."

He says such opportunities are best secured by Chinese companies conversing with European companies one-to-one at conferences.

Additionally, Haakma believes Chinese acquisitions can help European companies expand into China, particularly for industries that can take advantage of the country's growing number of middle-class consumers.

"It is a win-win situation without doubt," he says, explaining that many European companies would put part of their production into China to service the Asian markets after merging with their Chinese partners.

"It is very one-sided to say that we should protect these companies (from Chinese acquisitions), because many of them will go bankrupt if they do not change their mindset and think more internationally."

Haakma, 64, a Swede, graduated in law from the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands and, after a short time working at the university, started working for the Netherlands government.

From 1997 to 2002 he was the country's consul general in Hong Kong and Macao, during which time he also worked as chairman of the advisory board of the Dutch Business Association in Hong Kong.

In 2002 he was appointed consul general of the Netherlands in Shanghai and was also responsible for Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Anhui provinces.

He is well aware of China's economic reform, especially the speed at which Western businesses set up operations, initially in Hong Kong and Shanghai, but gradually more so in inland Chinese cities.

"A lot of second- and third-tier cities have set up economic zones and industrial zones, such as Wuhan, Chengdu, Qingdao, Dalian, Tianjin and Shenyang, which are very attractive for foreign companies," he says.

The competition between Chinese cities to give foreign investors support is one important reason for China to have so much foreign investment, he says. At the same time, the growth of the consumer market means investors can access their target customers in a more direct way by operating in China.

"When I was in Hong Kong, I was pleading with Dutch businesses to go to China and get familiarized with China. I told them to go and have a look at least."

Having seen the growth of Chinese outbound acquisitions, he says he would advise many European businesses to merge with an incoming Chinese company and put production in China through this company.

In 2007, Haakma joined TMF Group, which has eight offices in China, providing accounting, corporate secretarial and human resources, and payroll services to Western companies expanding into China.

Meanwhile, he has continued to help Chinese companies come to Europe and Dutch companies to go to China through the Netherlands Council for Trade Promotion.

Haakma is optimistic about Chinese investment in Europe, believing the Chinese will learn very quickly.

"It's happening. It's happening through failures, problems, failed deals and disappointments. Thirty years ago when Western companies went to China, they encountered the same failures, but I think the Chinese will accelerate faster, and their learning curve will be shorter."

Wang Mengzhen contributed to the story.

cecily.liu@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

Chinese Premier Li seeks point of balance

Reform roadmap before key meeting

Intel leaks proved justified: Snowden

Cooperation needed in terror fight

Beijing to further boost visa-free stay

Shenzhou X crew awarded for outstanding service

US to file murder complaint against LAX shooter

China's non-manufacturing PMI rises in October

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|