Fossil find in China reveals how first trees ripped themselves apart to grow

|

|

Dr Chris Berry with a fossilized tree trunk found in the Gilboa fossil forest, New York. [Photo provided to chinadaily.com.cn] |

A "stunning" fossil find in northwest China by a team of British and Chinese paleontologists has revealed the bizarre and unique anatomy of the world's first trees.

The exceptionally well-preserved discovery in an arid plain in Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region revealed that the Earth's first trees - known as Cladoxylopsidas - had more complex physiology than any modern varieties.

The findings were published in the United States journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and co-authored by paleontologists Chris Berry, from Cardiff University in the UK, and Xu Honghe of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

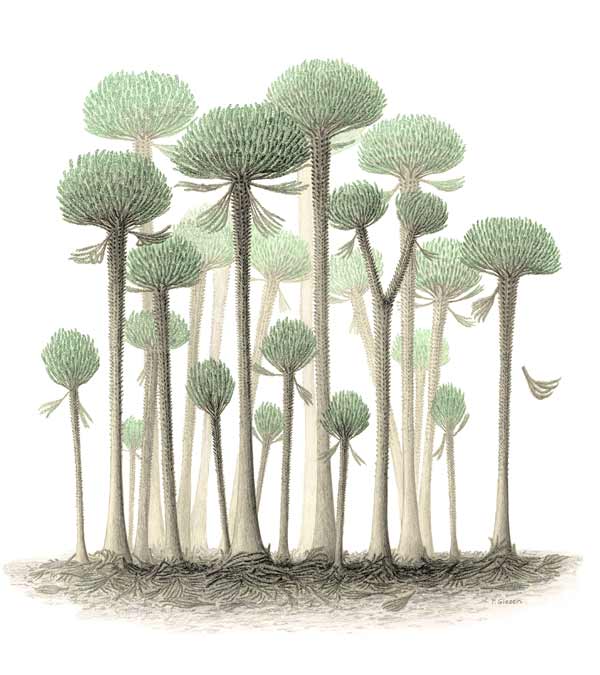

The fossilized trees grew more than 370 million years ago in the mid-Devonian period, when the seas teemed with fish and the land was populated by plants and crawling creatures, such as mites, scorpions and early insects.

The fossils reveal an interconnected web of woody strands within the trunk of the Cladoxylopsidas that is much more intricate than that of trees growing today.

"There is no other tree that I know of in the history of the Earth that has ever done anything as complicated as this," Berry said. "This raises a provoking question: why are the very oldest trees the most complicated?"

The woody strands, known as xylem, are responsible for conducting water from a tree's roots to its branches and leaves.

In most modern trees, xylem forms a single cylinder to which new growth is added in rings year by year just under the bark.

The fossils show the first trees had their xylem dispersed in strands in the outer five centimeters of the tree trunk only, while the middle of the trunk was completely hollow.

The narrow strands were interconnected to each other like a finely tuned network of water pipes.

"The tree simultaneously ripped its skeleton apart and collapsed under its own weight while staying alive and growing upwards and outwards to become the dominant plant of its day," Berry said.

The Chinese Academy's Xu discovered the first fossil in 2012 and the second, larger and better-preserved fossil in 2015. He went back to the site a year later with an excavation team to unearth the one-ton relic.

Berry said: "I've been working on fossil trees of this age for 20 years. These two fossils are the most stunning I've seen."

Previously discovered fossils had hinted at the complex anatomy of the Cladoxylopsidas, though none were in good enough condition to provide definitive evidence.

The trees in prehistoric China had fossilized in ideal circumstances, with silica from volcanic particles precipitating inside the plant cells, locking them in time.

Cladoxylopsidas did not have leaves.

Berry said it's not yet confirmed how they photosynthesized adding that the trees' unique structure maybe the result of how the smaller plants from which they evolved functioned, as well as a lack of competition in the environment from large, leafy trees.

"They turned into big plants with no constraints," he said. "There were no big trees with leaves around to shade them out or compete with them for nutrients and resources. They were successful for 30 million years - they were good in their day."

|

|

An artist's impression of a fossil forest. [Photo provided to chinadaily.com.cn] |