April Fool's Day is no joke – sometimes

In English-speaking countries, it's called April Fool's Day, in France it's called Poisson d'Avril, and in Germany it's ErsterApril. No matter what it's called, April 1 is the date where most countries in Europe, and some in Latin America, suffer a variety of practical jokes.

|

|

| A clown with balloons at a Clown Parade on April Fools' Day. [Photo/VCG] |

Different cultures take different approaches – in France the day is marked by people trying to attach a paper fish to the back of the unsuspecting victim, who walks about until someone yells "poisson d'avril!".

In Germany, newspapers are limited to one April Fool's joke story a day.

In Britain, it has become a tradition that newspapers print fake stories, although in the wake of US President Donald Trump's continual tirades in which he labels any story unfavourable to him as "fake news" it's debatable how long that tradition will last in this digital world.

Perhaps the most successful prank of all time was that perpetrated by the Guardian newspaper in the UK, a fairly highbrow publication with liberal leanings.

In the 1977, when there was no internet, no high-speed digital communications, and certainly no search engines, the Guardian ran an unprecedented seven-page supplement on a little-known republic in the Indian Ocean, named San Serrife, which consisted mainly of two large islands, Upper Casa and Lower Casa.

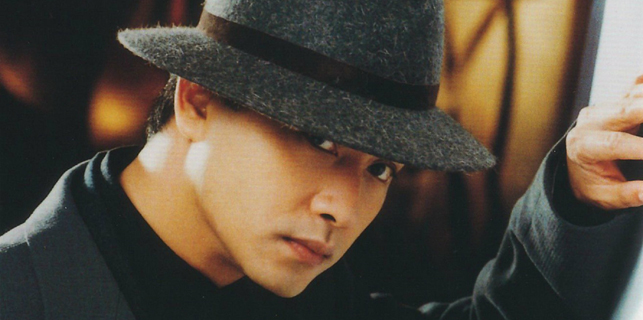

There was an in-depth interview with Maria-Jesu Pica, the young president for life, pictured complete with elaborate dictator's uniform and the obligatory dark glasses. His cousin, Antonio "Che" Pica, was in charge of trade union negotiations.

The Guardian's serious columnists at the time contributed in-depth articles on the economy, in particular its three main planks – minerals, tourism and oil.

What makes this first attempt at media April Foolery important is that the Guardian persuaded major advertisers to take space in the supplement and join in the fun.

Notable, Kodak asked readers in a quarter page ad to send in any pictures they had of the islands, and Guinness, the Irish brewer already noted for its leftfield ad campaigns, came up with the suggestion that a SAN Serriffe brewery had succeeded in brewing Guinness upside down, so the white head of the beer was at the bottom of the glass and the dark body at the top.

The Guardian made a lot of money from that, as advertisers eagerly took four of the seven pages of the supplement.

So successful was the hoax that the Guardian's switchboard the next day was jammed by thousands of callers wanting to find out about holiday opportunities in the country.

Of course, it was all a hoax, with the language throughout referring to various terms in the printing world – SAN Serriffe, (SAN serif) is a category of typeface, and Upper Casa and Lower Casa references upper case and lower case, or capitals and small letters.

The name of the so-called president for life, Pica, is in fact a print measurement.

Remember, this predated Google and Wikipedia by decades.

Subsequent efforts in newspapers have failed to meet that standard, most critics agree.

There was another, earlier media attempt which triggered a wave of controversy.

In1957 the august BBC, in its current affairs flagship program Panorama, hosted by the respected broadcaster Richard Dimbleby, ran a three-minute segment on a family in the Swiss Province of Ticino harvesting a bumper crop of spaghetti pasta from trees on April 1.

At the time, only 44 percent of Britons had a television, and pasta wasn't an everyday food, except canned in tomato sauce.

The BBC was besieged by listeners either asking for instructions on how to grow their own spaghetti trees, or complaining about the veracity of the report. The BBC eventually owned up, and subsequently faced widespread criticism for what some perceived as a waste of public money.