A viral mystery draws scientific detectives

Updated: 2013-07-14 08:06

By Denise Grady (The New York Times)

|

|||||||||||

|

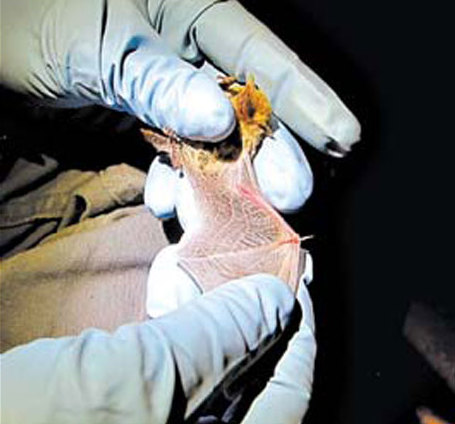

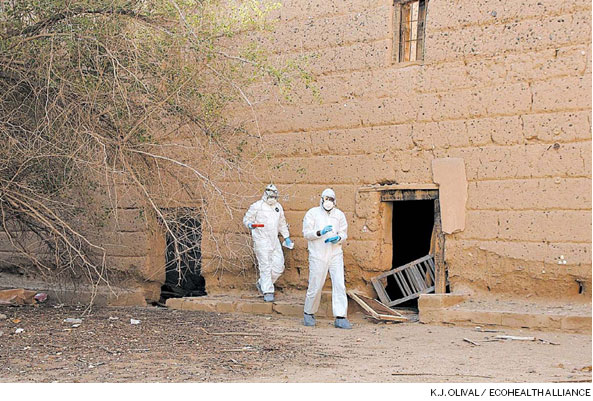

Scientists are searching areas near the places where there have been reports of Middle East respiratory syndrome, hoping to find its source. Taking samples from a bat to be tested for the coronavirus. J.H. Epstein / EcoHealth Alliance |

As the scientists peered into the darkness, hundreds of eyes glinted back at them from the walls and ceiling. They had discovered, in a long-abandoned village in southwestern Saudi Arabia, a roosting spot for bats.

It was an ideal place to set up traps.

The search for bats is part of an investigation into a deadly viral disease that has drawn scientists to Saudi Arabia. The virus, first detected there last year, is known to have infected at least 77 people, killing 40 of them, in eight countries.

The disease, Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome, or MERS, is caused by a coronavirus, a relative of the virus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, which originated in China and caused an international outbreak in 2003 that infected at least 8,000 people and killed nearly 800.

Scientists do not know where MERS came from, where the virus exists in nature, why it has appeared now, how people are being exposed to it or whether it could erupt into a much larger outbreak. The disease almost certainly originated with one or more people contracting the virus from animals - probably bats - but scientists do not know how many times that kind of spillover to humans has occurred, or how likely it is to keep happening.

Half the known cases have been fatal, though there almost certainly have been mild cases that have gone undetected. But the virus still worries health experts, because it can cause such severe disease and has shown an alarming ability to spread among patients in a hospital. It causes flulike symptoms that can progress to severe pneumonia.

The disease is a chilling example of what experts call emerging infections, caused by viruses or other organisms that suddenly find their way into humans. Many of those diseases are "zoonotic," meaning they are normally harbored by animals but somehow manage to jump species.

"As the population continues to grow, we're bumping up against wildlife, and they happen to carry some nasty viruses we've never seen before," said Peter Daszak, a disease ecologist and the president of EcoHealth Alliance, a group that studies links among human health, the health of wild and domestic animals, and the environment.

Saudi Arabia has had the most patients so far (62), but cases have also originated in Jordan, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Travelers from the Arabian peninsula have taken the disease to Britain, France, Italy and Tunisia, and have infected a few people in those countries. Health experts are also worried about the Hajj, the Muslim pilgrimage that will draw millions of visitors to Saudi Arabia in October.

The illness can be spread by coughs and sneezes, or contaminated surfaces, and people with chronic diseases seem especially vulnerable. More men than women have fallen ill, possibly because women have been protected by their veils.

Regardless of where they emerge, new illnesses are just "a plane ride away," said Dr. Thomas Frieden, the director of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While MERS is not highly contagious like the flu, he said, "the likelihood of spread is not small."

Finding out where the disease is coming from might make it possible to tell people how to avoid it.

Bats are the leading suspect, because they are a reservoir of SARS and carry other coronaviruses with genetic similarities to the MERS virus. Bats could be transmitting the disease directly to people, or they might be spreading it to some other animal that then infects humans.

Last October, a team of scientists from the Saudi Ministry of Health, Columbia University in New York and EcoHealth Alliance began scouring Saudi towns near where cases of MERS had been reported. A man led them to an abandoned village said to be hundreds of years old. There they found a small room that had become the roost of about 500 bats.

The scientists spent the night testing them for the MERS virus.

The animals can weigh as little as four grams yet have a 20-centimeter wingspan. "They're little flying fur balls," said Kevin J. Olival, a disease ecologist with EcoHealth Alliance.

It takes about 15 minutes to weigh and measure a bat, swab it for saliva and feces samples, and collect blood and skin for DNA testing to confirm its species.

If animals harbor the virus, does it make them ill? Do they infect people by coughing? Or do they pass the virus in urine or feces, and infect people who clean their stalls?

"The most common reason that wildlife viruses make the jump into people is that we do things that bring us and our livestock into closer contact with wildlife, such as the wildlife trade or agricultural intensification," said Dr. Jonathan H. Epstein, a veterinary epidemiologist with EcoHealth Alliance.

And, said his colleague Dr. Olival, finding the animals that carry the disease is "not just an academic exercise."

"It's a way to inform public health measures," he said, "to try to stop zoonotic diseases before they emerge into humans."

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/14/2013 page11)

Today's Top News

27 killed, 77 wounded in attacks across Iraq

French train derailment kills six: media

Former S.A President confident of Mandela

US seeking direct nuke talks with Iran

Soulik batters Taiwan, Fujian coast

Death toll rises to 43 in SW China landslide

Russia: no Snowden asylum plea yet

3rd Chinese girl dies in Asiana crash

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|