Fresh start for ancient village

Updated: 2013-10-10 07:23

By Zhang Yue (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Decades of logging left the people of Boduoluo village battling natural disasters brought about by deforestation. Now, a shift toward eco-tourism is reviving the remote area's fortunes. Zhang Yue reports.

The weeklong National Holiday was very busy for Liu Zhengwei, a 40-year-old farmer of Boduoluo village in Yunnan province.

Since 2008, the seven-day holiday has become the village's busiest season for tourists, and Liu, together with 96 others from the village's 31 families, have been busy guiding and accommodating visitors from all over the country and the world.

"This is not even the best time to visit Boduoluo village," says Liu, who provided accommodation for several tourists over the holiday. "The most beautiful time for Boduoluo is from April through August, when all the azalea on the mountain are in full bloom."

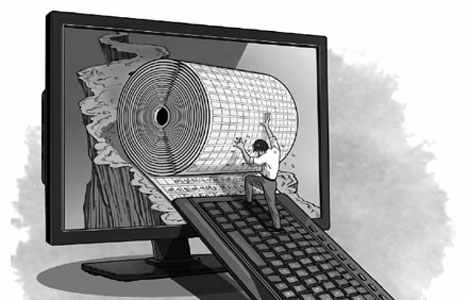

Azalea and forests give Boduoluo village beautiful views. Yet only a decade ago, local villagers earned their living by cutting down these trees.

The village, composed of the Yi ethnic group, is located in between two mountains, and is only 20 km from the old town Lijiang. Due to the village's high altitude of 3,200 meters and cold weather, very few crops can survive here and for decades local villagers relied on growing potatoes for food and cutting wood for money.

"People from other villages usually do not call the village by its full name, instead, they mock the village as 'potato plant' because we are too poor and only have potatoes to eat," Liu recalls.

Everything else had to be brought in from the foot of the mountain, which is at least three hours' walk. With very limited cash, villagers used potatoes to trade for rice and vegetables.

Besides potato, there is another thing that local villagers are good at harvesting: wood.

Today, Liu is unable to remember how he learned to chop wood when he was a teenager 20 years ago.

"You do not have to learn it particularly," he recalls. "Every man in the village knows well how to do it. Watch a few steps, learn about not hurting yourself, and then you join the rush."

According to 66-year-old Liu Zhengkun, former village director but more widely known as the "old village director", the wood chopping in Boduoluo reached its peak between 1985 and the late 1990s.

"Wood cut down from here was bought by outside peddlers at a very low price, and sold to Lijiang, sometimes even outside of Yunnan at a very good price," Liu Zhengkun says.

He vividly remembers there was even competition for wood cutting in 1985, when the Naxi ethnic group, who lived at the foot of the mountain, rushed to Boduoluo and started cutting their trees because trees in their area had already been cut down.

"That was the time when the country was going through massive construction, and since the late 1990s, large amounts of wood were transported to Lijiang to support tourism construction there," Liu Zhengkun recalls.

Like all the middle-aged men in Boduoluo village, wood chopping has left Liu Zhengwei with ugly wounds on his calves that are still visible after 20 years.

However, the scars are more than skin deep.

It did not take long for villagers in Boduoluo to feel the pain of deforestation. Wind damage, floods and landslides started to hit the village more frequently as the village lost its protection from the forest.

A devastating flood hit the area in the late 1990s, and a family with three people, mother, father and son, were killed.

That was when Liu Zhengwei and the other villagers met Yu Xiaogang, a 62-year-old environment activist who was pursuing his doctorate degree at the Asian Technology Institute in Thailand, majoring in watershed management.

"Watershed management is a new trend worldwide and China did not even know what it was back then," Yu recalls. "I was in Boduoluo to study the protection of natural forest in the upper and middle Yangtze River for my doctorate degree thesis."

Yu was shocked at the bare mountain.

Yu later abandoned his degree to devote himself to forest restoration. In 2002, he founded an environmental protection non-governmental organization called Green Watershed, in Kunming, Yunnan.

This confused Liu Zhengkun and his fellow villagers at first.

"The man tried to persuade us not to rely on cutting down trees for a living," Liu Zhengkun says. "But what will we rely on for a living? How are we going to support ourselves?"

As Yu recalls, that was a "difficult conversation".

"Because very few villagers speak Mandarin, they speak only the Yi ethnic language, we could not understand each other," Yu says.

That was when Yu met Liu (Zhengwei), who speaks comparatively eloquent Mandarin and finished his first year of middle school, a very good education for a villager born in the 1970s.

Liu met with Yu in the summer of 1998. Though Liu did not completely understand Yu's idea of ecological restoration, Liu decided Yu was a "good man" because the 62-year-old visited the village frequently to talk about his idea and helped two girls who had dropped out of school due to poverty.

To help Liu understand the connection between wood chopping and natural disasters, Yu took Liu and some other villagers to Honghe county to learn from the successful examples there.

"I gradually understood his idea that we should not cut down the forest for whatever reasons, because the forest is our natural protection from any damage and disaster," says Liu, who was among the first people to agree with Yu's idea of forest conservation.

Today, thanks to Yu and Liu's work, the village now earns most of its income by growing herbal medicine such as Maca, which Liu invited instructors to teach local people about.

For the past 10 years, Liu has worked as a middleman between Yu's organization and local villagers using Mandarin and the ethnic language to provide the poverty stricken village with a better life.

Green Watershed, which has been receiving funds from Oxfam, the Hong Kong-based foundation that works to fight against poverty, also helps to educate the villagers.

Since 2000, the village has had electricity and run an evening school for women, in which Liu teaches local women Mandarin and basic math.

"The evening school is also a good opportunity for me to give them knowledge about environmental protection," Liu laughs. "But things have to go very slowly because environmental protection is a completely new notion to them."

Contact the writer at zhangyue@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 10/10/2013 page20)

Today's Top News

Premier Li proposes ASEAN plan

New speculative fund inflows

Obama picks Yellen for top Fed job

Japanese stance concerns diplomats

Snowden to hunt job in Russia

CNOOC offering 25 blocks for cooperation

Li plans to seek deeper trust with neighbors

Obama says he'll negotiate once 'threats' end

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|