A village devoted to a dance

Updated: 2012-03-25 07:44

(The New York Times)

|

|||||||||||

|

Photographs by Briana Blasko for The New York Times. |

In India, keeping a classical dance style alive has become a group calling

A four-week visit to India made me feel that now I have witnessed dance where it is truly central to culture.

In the disciplined utopia of Nrityagram, a village an hour's drive west of Bangalore and completely given over to dance, it is not unusual for people to dance - usually with live musicians - morning, noon, and night.

The village's company, the Nrityagram Dance Ensemble, directed by Surupa Sen, is a lustrous exemplar of Odissi, one of India's classical dance forms. I stayed in this village for four days, observing as the company prepared for an overseas tour this month, including stops in New York, Louisiana, Iowa and Mexico. In April it will offer workshops at the Mark Morris Studio in Brooklyn.

The company's foreign travels do much to keep the village financially afloat. Nrityagram was founded in 1990 as a gurukul, or residential village of learning, by the actress Protima Bedi, a compelling exponent of Odissi.

India has no fewer than eight genres of dance that have been officially deemed classical. The country's complex political and social history, however, brought most of these forms close to extinction by the 1950s. Most were connected to devadasis, a legendary and now virtually defunct caste of temple dancers, some of whom were concubines, some vowed to chastity and some prostitutes.

Though the forms have become well established again, they've been extensively reconstructed during the last century. For the Indians, classicism is intimately linked to the spirit of national independence and to the pride of individual states. It is also a way of touching base with a tradition that existed before Western and other colonial invasions.

Odissi derives from the state of Orissa on India's east coast, and a few Orissan purists assert that Nrityagram detaches the dance form from its home culture. The truth, however, is that the village's inception coincided with the worldwide spread of Odissi as a boom dance industry.

|

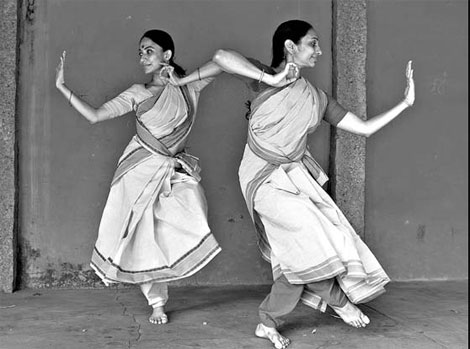

What's special about Odissi? Its most distinguishing features are its sensuous shifts of weight (creating a series of S-bend curves primarily at knee, torso, and neck), its rhythmic phrasing and its connection to ancient sculptural depictions of dance. Like many of the dance forms of Southeast Asia it derives from the Natya Shastra, the treatise on the performing arts written between 200 B.C. and A.D. 200.

Yet this ancient form is also a new one. Core features have been codified only in living memory and are still subject to debate.

Certainly Odissi's range and rich beauties deserve to be called classical. Like several other classical forms in India, it has large capacities both for pure form (nritta) and for poetically dramatic expression (abhinaya). At Nrityagram it's spellbinding, in the abhinaya sections, to watch the dancers' facial mobility and rapt gestural communicativeness.

The production that is about to tour is a joint project, yoking Nrityagram dancers and musicians with a guru, choreographer, drummer and two dancers from the Chitrasena Dance Company from Colombo, Sri Lanka. (The Kandyan dances of Sri Lanka, which the Chitrasena performers practice, form yet another of the many genres of the Indian subcontinent.) The production, called "Samhara," is a remarkably subtle dialogue between the two styles. Nrityagram's dancers refer to Chitrasena as the masculine counterpart to the essentially feminine Odissi style.

The two Sri Lankan dancers involved in this project are remarkably lovely, slender, and long-limbed young women. Soon, however, the difference between their idiom and the Nrityagram one becomes obvious. The Chitrasena women cover much more space than the Odissi dancers, both in the easy vertical lift of their limbs and in their horizontal traveling. They show few of the meltingly sensuous horizontal curves that are central to Odissi. They also show facial enthusiasm with broad smiles, whereas the Nrityagram dancers, like most Indian classical stylists, maintain facial composure in passages of pure dance form. And where Odissi dancers wear a chain of bells twined three times around the ankle, the Chitrasena dancers wear bronze anklets with internal bells, attached both to ankle and second toe.

A Western observer begins by finding everything in Indian dance "other." What becomes absorbing, however, in Indian dance is that it contains multiple othernesses.

These Indian dances abound in dualisms: masculine and feminine elements, sculptural qualities and sinuous transitions, abstract form and mime gesture, motion and repose. The contrasts within the idiom make for endless expressiveness.

The New York Times

|

Odissi, a dance style performed in Nrityagram, India, is distinguished in part by its connection to ancient sculptural depictions of dance. Briana Blasko for The New York Times |

Today's Top News

President Xi confident in recovery from quake

H7N9 update: 104 cases, 21 deaths

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|