Channeling the flow

Updated: 2012-01-12 10:33

By Zhu Zhou (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

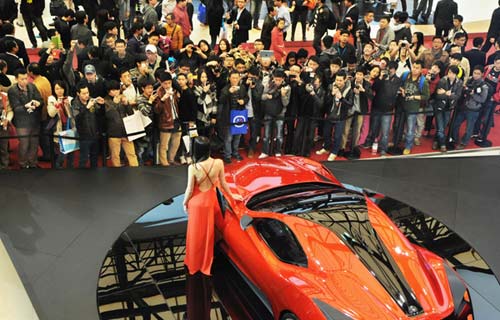

From top: The "plowshare mouth" divides the water flow of Xiangjiang into southern and northern canals of Lingqu. One of many old stone bridges spans the Lingqu Canal. Traditional lanterns decorate a street in Xing'an's old downtown. An old man walks along the canal embankment. |

The Lingqu Canal, possibly China's least-known ancient wonder, reveals the currents of history with its wealth of treasures - both cultural and technical. Zhu Zhou reports.

After the first Qin emperor (Qin Shihuang, 259 BC-210 BC) defeated the six other kingdoms of the Central Plains, he put in place two military strategies: first, build the Great Wall in the North to keep out the nomadic tribes who made occasional forays on horseback into the wealthy Central Plains; second, subjugate the less developed southern area known as Baiyue. One of his half-million-strong five units on the southern expedition reached Xing'an, a county in what is now the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, and was ordered to construct a watercourse that would enable the Qin troops to travel by boat all the way into the deep south.

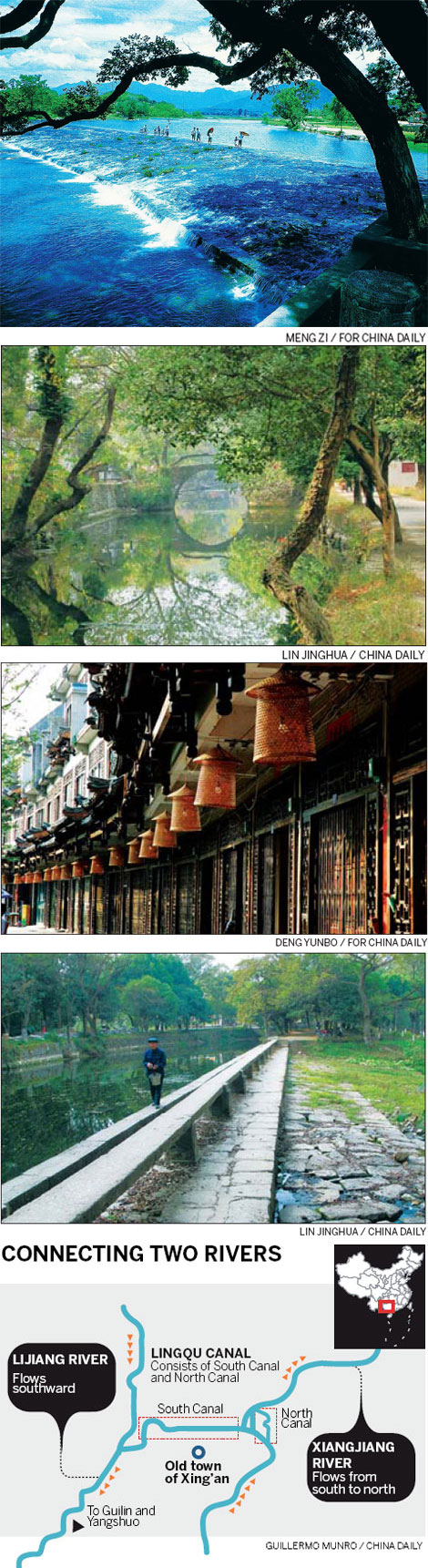

Xing'an is the originator of two major waterways: Guilin's mother river Lijiang, which flows through the now world-famous tourist hot spot, and Hunan's Xiangjiang, which is the province's mother river. The former proceeds south and discharges into the Pearl River while the latter winds north and empties into Dongting Lake, which eventually joins the Yangtze River.

However, the two rivers do not intersect each other, even at their fountainheads. At their closest, they are only 20 km apart. The absence of a natural waterway linking the two became a major inconvenience when the first emperor of a unified China went on campaigns against what is now Guangdong province and Guangxi. The mountain ranges blocked the Qin troops, and provisions could not be moved in time to supply the advancing army.

Hence, plans for Lingqu Canal were hatched - and were completed in 214 BC. Shortly afterward, Baiyue became part of China proper.

Compared with the Grand Canal of China, Lingqu Canal is a gem hidden from view. While the Grand Canal, which runs for 1,747 km between Beijing and Zhejiang province capital Hangzhou, was finished in 1293, Lingqu flows for just 37.4 km and never outside one county. Even so, it's claimed by some experts to be the world's oldest contour canal.

But age tells only half the story. Lingqu, in the deep mountains of northeastern Guangxi, ultimately connects two of southern China's mighty rivers - the Yangtze and the Pearl - and was partly the reason China expanded its territory some 2,000 years ago.

What started as a military transport line turned into a busy trade route. In the ensuing dynasties, the canal was improved, and boats as big as 22-meter-by-2.8-meter and carrying cargoes of up to 17.5 tons could travel between the natural watercourses. On the busiest day, as many as 200 boats would pass through the canal.

Then, in 1938, the fate of the canal was sealed as a railroad and a highway were opened, linking Hunan province and Guangxi. Trade dwindled on the artery until the early 1970s when it completely vanished, recalls Liu Jianxin, chairman of the Lingqu Historical Cultural Research Society.

"Of the three big building projects of the Qin Dynasty, the Great Wall was purely military and Dujiangyan in Sichuan province was for civilian use, but Lingqu was built for military purposes and evolved into a civilian waterway," Liu says.

Whatever the initial purpose, all the projects have ended up as tourist attractions. However, the crowds at Lingqu are sparse at best. Of the 30 million people who thronged to Guilin in 2011, only a fraction trickled to Xing'an, which is administratively part of Guilin.

But things will change, Luo Yongdong, Communist Party secretary of Xing'an county, says.

"Guilin's tourism industry is like a shoulder pole, with downtown as the fulcrum, and Yangshuo on one side and Xing'an the other," he says, quoting an oft-repeated analogy. The canal is 60 km from downtown Guilin. The driving time will be shortened from 1.5 hours to 30 minutes when an expressway is opened in early 2012. A yearlong advertising campaign will be launched on both national and provincial television networks.

That is good news for Ai Zhijia, a farmer from Nandoukou village, which sits at the fork where the river bifurcates into the Xiang and the canal. Like many of his fellow villagers, the 33-year-old rows a boat down the 3-km-stretch where the canal cuts into the center of the county town. On a good day, he can make 10 such trips, bringing home a monthly income of 2,000-3,000 yuan ($317-475).

Ai also owns a riverside hostel where tourists can dine and lodge. That earns some 200,000-300,000 yuan a year. His is only one of a dozen such taverns in the village of 420 people.

"I used to go fishing when I was a kid," Ai says. "We would build a bamboo net and end up with a 50-kg catch every day. But the peak period lasted just two months when fish tried to swim upstream, but the prices were so low at the time that we could not make much."

Nowadays, he's happy if he can net 10 kg of fish. But he does not need to sell them anymore, as his eatery has a steady demand.

As the boat cruises down the canal toward downtown, old shops emerge in denser clusters. It takes on a growing resemblance to the bustling old town of Suzhou in Jiangsu province, with stone bridges and traditional architecture that, save the neon lights, would make historical celebrities of yore very comfortable.

One of the bridges is called Wanli - literally 10,000 li or 5,000 km, which is said to be the distance to the then capital city of Chang'an but is often used figuratively to refer to extreme remoteness. Many an ancient official was exiled to this outpost as a punishment. And when they stood on this bridge, they could only lament how far they were removed from the power center.

The Horse-Neighing Bridge is said to have been built in AD 42 by a southbound general named Ma Yuan. To quell a rebellion by a local tribe, Ma needed to cross the river, but his horse would not step on the bridge and neighed incessantly. It turned out the horse had a premonition that the bridge would buckle under their weight. Ma therefore organized a donation drive to rebuild the bridge and dredge the canal, among other improvements.

"Lingqu is the junction where the primeval Chu culture of the North and the Yue culture of the South touched and enriched each other," Party secretary Luo Yongdong says. "Hopefully, new visitors will be fascinated by this town where so many figures of historical interest have passed through."

Today's Top News

President Xi confident in recovery from quake

H7N9 update: 104 cases, 21 deaths

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|