Tips and Articles

Following in Lu Xun's footsteps

Updated: 2011-03-10 07:55

By Chitralekha Basu (China Daily)

|

The stone statue of Lu Xun at Lu Xun Museum in Beijing. |

A visit to the Lu Xun Museum for a look at the life and times of 20th century China's best-known writer is an inspiring experience. Chitralekha Basu reports.

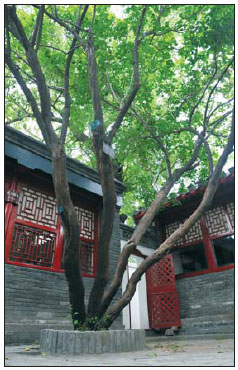

No 19, Fuchengmen Inner Street, Xicheng district, Beijing, is a tiny courtyard house, almost squashed to one side of the 12,000-square-meter compound that now houses the Lu Xun Museum.

|

This courtyard house was Lu Xun's home between 1923 and 1926. Lu Peng / Xinhua |

This was where Lu Xun (1881-1936), who many say gave Chinese literature its modern form (baihua), wrote Chaohua Xishi (Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk) - his reminiscences from childhood to early youth - the poems that went into Ye Cao (Wild Grass), and several short stories like Pang Huang (Wanderings).

Lu Xun lived here in 1923, after falling out with younger brother Zhou Zuoren, with whom he shared an intense and layered relationship.

Zhou had followed Lu Xun (then Zhou Shuren) to Japan on a scholarship in the early 1900s. Lu Xun was a scholar, the first foreign student at Sendai Medical Academy.

The image of a blindfolded Chinese "spy" - now part of the exhibits, being beheaded by Japanese soldiers fighting the Russo-Japanese war, even as a gaggle of Chinese onlookers watched dispassionately - seen as part of a slide show after classes at Sendai, changed all that. Lu Xun abandoned the sergeant's knife for the pen, moved to Tokyo and began his work of nation building.

It was in Tokyo that the brothers shared notes on world politics and talked about introducing Chinese readers to literature from other cultures. They collaborated on a two-volume translation of short fiction culled from Russia, the United States and Eastern Europe, Yuwai Xiaoshuo (Tales from Abroad).

But while Lu Xun saw himself as a warrior of the revolution, sweeping across the country in the wake of the May 4th, 1919 movement, Zhou Zuoren was less of a radical and more of an aesthete - hence, the inevitable clash.

Lu Xun's study is small and spartan. A charcoal sketch by his favorite German artist, Kaethe Kollwitz, whose works Lu Xun had compiled and published at his own expense, hangs above the table.

The stories Lu Xun wrote here, between 1923 and 1926 - until he left Beijing for Fujian province's Xiamen, shattered by the massacre of students protesting against the warlord regime on March 18, 1926, in which two of his female students died - are fraught with an overpowering sadness, as opposed to the biting satire that dominates his earlier milestone works, Kuangren Riji (A Madman's Diary) and A Q Zhengzuan (The True Story of Ah Q).

In group photos, Lu Xun comes across as a diminutive man whose personality is defined by his broad forehead, high cheekbones and firm jaw line. He doesn't smile much in the photographs, but sometimes his eyes do. As in the one in which he holds his 1-year-old son, Haiying, who was born to him at the relatively late age of 50.

Haiying's birth culminates the love story between Lu Xun and his student Xu Guangping, who followed him through thick and thin - mostly thin, given that Lu Xun had lost his job in 1926 for openly supporting the students' movement, was blacklisted by the warlord government and was practically on the run.

They moved to Xiamen and then to Guangzhou. Chiang Kai-shek launched a combing operation against his Communist allies, which spread to Guangzhou in April 1927. Many of Lu Xun's students were arrested and he was himself a wanted man.

Lu Xun and Xu found asylum in the foreign concession area in Shanghai, where he experienced one of his most productive phases, writing polemical essays on Confucius and Dostoyevsky, heading the League of Left-wing Writers, compiling ancient Chinese and foreign artworks - woodblocks, engravings and such like.

His collection of books (140,000), engravings and stone rubbings (6,000) from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) was huge and only a selection of it is on display.

A connoisseur of art since he was a teenager, when he would collect books of ink-and-brush drawings, Lu Xun's own felicity with the pen and brush was extraordinary. Handwritten articles by him look like printed sheets, each character mapped and drawn with machine-like precision. The logo he created for Peking University could rival some of the finest in modern design.

The Lu Xun Museum in Beijing is easily one of the most detailed shows on the life and times of 20th century China's best-known man of letters and has 21,482 cultural relics under one roof. At the same time, the show also throws light on a multifaceted man with powerful artistic sensibilities, extraordinary passion and overwhelming concern for humanity.

"A road is created by treading on a space where none existed," reads a comment by the writer, etched in relief at the entrance to the exhibition hall. For those interested in checking out the road that Lu Xun charted - not just in terms of developing a new literary vocabulary but also encouraging free flow of thought, fostering a spirit of rebellion against oppressive rulers - the journey could start right here.

E-paper

Green light

F1 sponsors expect lucrative returns from Shanghai pit stop

Preview of the coming issue

Toy for rich boys

Reaching out

Specials

Share your China stories!

Foreign readers are invited to share your China stories.

No more Mr. Bad Guy

Italian actor plans to smash ‘foreign devil’ myth and become the first white kungfu star made in China.

Art auctions

China accounted for 33% of global fine art sales.