Media failed Wu in life and even in death

Wu Yongning, known for scaling skyscrapers without safety equipment to snap astonishing selfies, died last month after slipping off a 62-story building in Changsha, Hunan province. The video of the 26-year-old's accidental fall went viral online about a month later.

The martial arts-trained stuntman who had also worked in films, was an online celebrity and, reports say, aimed to use the about $15,000 he expected to earn in prize money from the stunt to fund his wedding and pay for the treatment of his sick mother.

The online release of the video of Wu's fall by some media outlets has come as an added shock to his already aggrieved family, and evoked strong public reaction. Although the media outlets later deleted the video and apologized to Wu's family as well as the public, they should have reflected on their professional ethics and social responsibilities before releasing the video.

A celebrity on social media platforms such as Weibo and some live-streaming channels before his death, Wu described himself as "the first person" of high-altitude extreme sports in China. But his stunts, which Western media call "rooftopping", were part of an extremely dangerous adventure rather than extreme sports.

Extreme sports, which carry high risks, require years of expert training and necessary safety precautions. Performing dangerous stunts on the rooftops of skyscrapers without any safety equipment is more like playing a potentially fatal game, and considered a public safety threat in many countries.

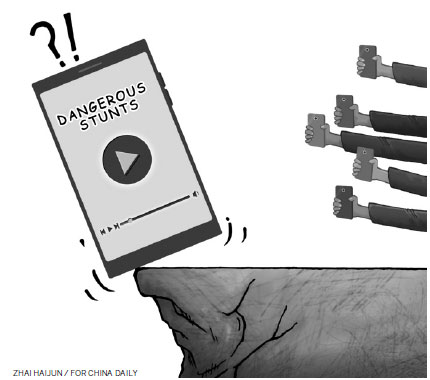

What drove Wu to take the extreme risk time and again was not only the excitement of "rooftopping" but also the fame and direct economic benefit it brought thanks to the audiences' attention he got through social media networks.

The money he earned by performing the dangerous stunts, which were livestreamed, stimulated him to indulge in more dangerous acts, which unfortunately ended in his death. People should be responsible for their actions, and Wu paid with his life for the choice he made, which nevertheless was tragic. But social network platforms, including those live-streaming Wu's stunts, have to share some of the blame for his death.

Wu had been fined and punished several times for endangering public safety, and the spread of the stunt videos is not a healthy sign. But the livestreaming platforms that aired his videos cared only for the public attention and revenue Wu's stunts got them, and therefore "encouraged" him to take the road of no return. The live-streaming platforms' decisions were not conducive to public order.

What some media outlets have done after Wu's death is worse. They browsed Wu's mobile phone and recorded his last, tragic "rooftopping" video, and after interviewing his heartbroken family recently, released the two clips simultaneously in the hope of increasing their ratings by getting high numbers of users' clicks.

Facing an outcry from Wu's family, the media outlets argued that their reporters copied the mobile phone video in front of the family. The subtext of the media oulets' excuse is that his family permitted the release of the video. Wu's family members are simple rural residents who had never met a journalist before, so they didn't know what the reporters who interviewed them would do with the video.

These media outlets have violated the privacy of this simple rural family, even aggravated their sorrow, by releasing the video to the public. And even if Wu's family didn't mind the media outlets making the video public, professional ethics, if the media outlets have any, should have prevented them from releasing it. They should also have realized Wu's stunt, despite its failure, could influence some other youths to try their hand at it.

As one of the most important social instruments, the media should be aware of the influence they wield and the social responsibilities they have to fulfill. If the media's purpose is just to catch the audiences' attention and make profits, the harm they cause through such actions will far offset the positive social role, if any, they play.

The author is a writer with China Daily. wangyiqing@chinadaily.com.cn