In search of Turpan

|

|

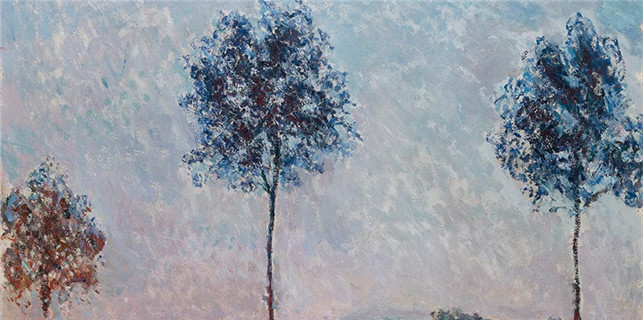

Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves 1996. [Photo by Bruce Connolly/chinadaily.com.cn]

|

The focal point of an oasis such as Turpan is the bazaar - a mixture of scenes including parking areas for donkey carts. Blacksmiths re-shoeing mules. Pens enclosed bleating goats. Nearby spread an extensive wholesale area for raisin trading. Trucks were bulging with red and green peppers, onions, melons, walnuts, sweet potatoes and much more. Walking through the market some sections specialised in carpets which Xinjiang is renown for; household essentials like stoves; hats, knives, reams of colourful cotton ready for dress making.

Shaded food stalls were stacked with fresh baked nan bread alongside grilled lamb shashlik and roasted chicken accompanied by the aroma of spices and cooking smoke. Large areas were stacked with fresh local fruits and vegetable. Meat tables heaved with great chunks of lamb. Bargaining was the norm between buyers and sellers, mostly women in their daily ethnic attire. Just as with Urumqi's Erdaoqiao, I would sit at a stall near a leather boot seller, have a cold drink, watch the scene while regularly being a topic of curiosity.

North of urban Turpan lies Grape Valley (putao gou). Along this narrow pass grapes dangled from extensive wooden trellises. Dry, hot air leads to very high sugar concentration in fruits, particularly grapes, increasingly used in the production of excellent wines. Many seedless grapes are dried over a 40 day period within unique outdoor brick drying rooms or 'chunche' to produce raisins. Regarded as some of the world's finest, over 75% of China's raisins come from around Turpan. The valley a pleasant location to relax, sample delicious green or dark grapes while wandering around a mini-bazaar displaying ornate knives alongside waistcoats embroidered in golden thread. Fun also trying to converse with locals who seemed to enjoy sitting on large wooden beds set up outside their compact homes.

Despite having an arid climate, agriculture and indeed life itself was rendered possible through the unique Karez underground irrigation system. Man-made tunnels, some going back 2000 years, carried glacial meltwater down from the Bogda Mountains to points around Turpan. Some aqua-passages, cut physically by hand, have visitor access to view both the construction and flow of clear water.

Gravelly wastes east out of Turpan revealed mounds of stone, access points to the Karez. Telegraph poles lined an empty road towards the arid, seemingly purple-red, Flaming Mountains (huoyanshan) - geologically a 'thrust fault belt' rising to 831 metres above sea level. A geologist's paradise with so many rock contortions not hidden by vegetation! The route led towards a narrow ledge above West Mutou Valley with the river split into several brownish channels. Statues reminded of the area's association with the fabled 'Journey to the West'. I was heading to the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves (bozikell quango dong) mostly dating from 10th to 13th centuries. Accessed from a renovated terrace they were cut into a cliff face fronting the waters. Nearby, a mother in black headscarf and her daughter in red, sorted raisins, bagging them for loading onto a donkey cart.

Turpan was a place for walking - so much to see. I would spend every day exploring while watching with fascination so many unfamiliar scenes. A few minutes from city centre I would be amongst grape fields surrounded by irrigation canals with corn cobs drying outside brick courtyard homes. Goats wandered freely, cows remained in mud-walled stalls.

Two kilometres walk from downtown, Emin Minaret (Sugong Ta), is readily identifiable as an iconic symbol of Turpan. Its elegant circular and tapered 44 metres tall dome has a richly textured exterior of geometric, floral mosaic patterns combing Chinese with Islamic features. Constructed from adobe bricks in only one year, this tallest minaret in China dates back to 1778. Honouring a former local general, Emin Khoja, it rises beside a mosque with a large internal courtyard. As I arrived a service was finishing, groups of men heading off either on tractor or donkey carts. Although not possible to climb the tower, steps did lead onto the main hall's roof for close up examination of the minaret's workmanship.

Along fertile Yarnaz valley, eight kilometres from Turpan the Ancient City of Jiaohe sits on a thirty metre high plateau bounded by two rivers creating a natural defensive position - it had no walls. With a history going back almost 2000 years it grew as an important Silk Road centre during the Han Dynasty but abandoned in the 13th century following destruction by the warriors of Genghis Khan. Walking through the ruins it was possible to trace what were principal roads, while looking at what had been major buildings and Buddhist temples. I could imagine the bustling movement of traders with camels, soldiers, officials and local people in ancient times. Jiaohe occupies a stunning location with the green surrounding oasis contrasting with nearby desert aridity and lifeless, waterless ruins. In 2014 it became one of the Silk Road UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Despite being October evenings were warm. Cafes with outdoor terraces were locations to dine in the setting sun watching boys racing around the dusty streets on their donkey carts while older generations sang and danced in adjacent restaurants. Turpan had been in my mind for many years, there was contentment at finally being there but soon I would have head out of this enchanting oasis for more adventures east along the Silk Road.