Online shopkeeping effort falls on stony ground

|

|

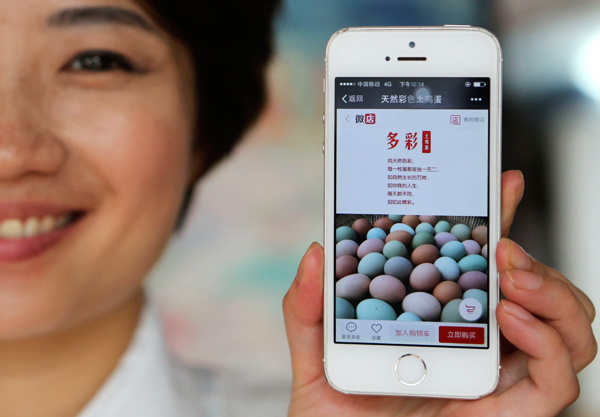

A woman in Rongshui, the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, shows an egg shop set up on social networking app WeChat. LONG TAO / FOR CHINA DAILY |

I had never expected that I would one day try my hand at running a store on social networking app WeChat.

It is called yunji, literally translated as "cloud market", an app that links you with brand products ranging from cosmetics to kitchenware.

Once registered, you can choose to be either a consumer who can buy at a discount, or a store operator who may make some money by posting product information on your WeChat account, using a quick response code or purchase link that may enable a transaction to be completed.

The idea behind the app is to make full use of your social networking connections and turn them into a source of additional income.

Unlike those who run stores on online marketplaces like Taobao or Tmall, a yunji operator doesn't have to hold an inventory of products and take care of logistics. All you have to do is to promote products on WeChat. You act like a salesperson and get kickbacks based on how much you sell.

I happened to learn about yunji from one of my college classmates, a very quiet woman. About a month ago I suddenly found her active on WeChat, posting information about products of all sorts while trying to persuade her WeChat friends to buy.

The response she got was lukewarm, at far as I could tell in the group where I interact with her and other classmates. I seemed to be the only one who gave a thumb-up for her postings, out of courtesy. I doubted anyone in the group actually bought from her.

It was not surprising. As WeChat is becoming a new frontier for business competition, product advertisements found there have sparked rising public aversion.

So when my classmate invited me to jump on the wealth bandwagon of yunji, the biggest question in my mind was whether my wary WeChat friends will accept it as a useful platform to buy quality products at bargain prices rather than just another source of pestering ads.

"They will if you try hard," she assured me. "In an era of sharing economy, yunji will surely become a new way of life. Why not just give it a try?"

Partly out of curiosity and partly because I hate to say no to a well-meaning old friend, I accepted her invitation.

Of course it was not a free-ride. Registration was invite-only, and I had to pay 365 yuan ($53.2) for a one-year membership fee. In return, I got a cosmetics set said to be worth the same amount.

After downloading the app using a code my classmate sent me, I was fully set for a business career.

It turned out to be a bumpy road ahead.

Shortly after I promoted the first batch of products ranging from French wine, flasks, towels to Ferrero Rocher chocolates, I got several inquiries from my friends about whether my WeChat account had been hacked.

That evening my wife told me that a common WeChat friend of ours had complained to her about what she saw as nuisances, and put me on a blacklist, forcing me to write a short WeChat message explaining what I was actually doing and asking for forgiveness from those who feel offended.

Of course I also received some thumb-ups, but they in the end never turn into transactions deals.

So one week after I opened my store, I got only two deals sealed, one from a colleague who trusts me well that I will never cheat her and bought three packs of dried mushroom for 79 yuan, and the other by myself for a case of yogurt for 59 yuan.

The profit I have made after all these misunderstandings and doubts about my integrity: a meager 6.9 yuan.

So that's enough about the story of my wealth.