RCEP has to be more inclusive than TPP

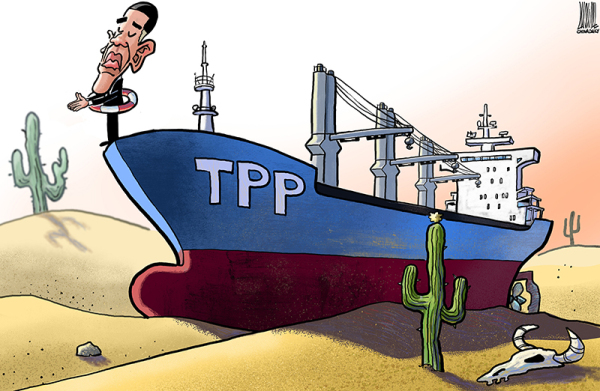

Although US President Barack Obama has urged other Trans-Pacific Partnership member countries to continue working to advance the agreement, the outlook for the TPP is uncertain. US president-elect Donald Trump struck an anti-TPP posture during his election campaign, and has said the United States will withdraw from the trade deal on his first day in the White House.

For the rest of the TPP member countries the bleak prospects for the trade deal are a great disappointment. While they are expected to continue efforts to persuade the Trump administration to look positively at the TPP, they do not appear hopeful at this point in time. The assumption among these members appears to be that the US would not commit to the TPP at least for the time being. This is forcing the non-US TPP members to consider the possibility of having a TPP without the US.

A trans-Pacific trade deal without the US is a theoretical possibility, which would increase if the US voluntarily withdraws from the TPP. At present, the TPP agreement requires ratification by at least six of its members accounting for a minimum of 85 percent of the GDP of the group. This makes it impossible for the TPP to become functional without its ratification by the US and Japan — the two largest economies in the group. If the US withdraws from the TPP, then Japan and the rest of the members can ratify and implement it.

But a TPP without the US — the world’s largest economy — would not be as significant a trade deal as it is now. The absence of the US might also lead to new discussions on many aspects of the TPP. Non-US TPP members were persuaded by US negotiators to make several concessions for suiting US business interests. These are particularly relevant for the TPP’s provisions on intellectual property protection for biologic drugs and investment-state dispute settlement (ISDS) rules. Countries having made such concessions would wish to revisit them if the US were no longer in the picture.

Besides, non-US TPP members would be looking forward to exploring other alternative frameworks for regional economic integration. The most feasible option in this regard is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. Several non-US TPP members — Australia, Brunei, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore and Vietnam — are negotiating the RCEP. With more than one-third of the global economy and almost half of the world’s population, the RCEP is a powerful economic grouping. In addition to the non-US TPP members, it has China, India, Indonesia and the Republic of Korea and all the 10 ASEAN economies. The size of the group is large enough to create one of the world’s biggest free trade areas offering significant new economic opportunities for all of its members.

As the largest economy in the RCEP, China will have a critical role to play in its growth. So will Japan, Australia and India as the other large economies in the region. Unlike the TPP, which from a geo-political perspective was a grouping of US defense allies and partners, the RCEP is not a collection of China’s allies. There are many members in the RCEP with whom China has difficult political relations. Going ahead, the challenge for RCEP and its major members will be to overlook existing political differences and contribute as co-rule makers in the establishment of a new regional trade framework.

A successful RCEP will create the momentum for the establishment of a Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific. The problems encountered by the TPP drive home the importance of working toward “inclusive” trade frameworks that try to accommodate as many diverse interests as possible. Such an approach might sometimes prevent trade agreements from being too ambitious. But it will set in motion a process of gradual opening up with less political resistance. It would also help in diffusing the anti-trade sentiment sweeping across the world today. A balanced RCEP might become the model for future mega-regional trade agreements.

The author is senior research fellow and research lead (trade and economic policy) at the Institute of South Asian Studies in the National University of Singapore.