City a microcosm for reform challenge

Updated: 2016-06-10 08:32

By Ed Zhang(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

Suzhou highlights to me how hard it still is to make cross-industry and interdisciplinary changes

A recent trip to Suzhou, one of the wealthiest cities in the Yangtze River Delta, was illuminating for me in terms of seeing where China stands, its opportunities and challenges.

Why does the country's present reform seem so hard? Other than the continual nuisance of the economic slowdown, which at times threatens to throw the stock market into disarray, there are other complications. There is one kind China has hardly confronted in the past.

Most of the reform initiatives that have been successful so far are the ones that attack a problem in one industry or one area. After dismantling the commune system, agricultural reform allowed the trade of most farm products at market prices.

Then, there was a reform of state-owned enterprises, to regroup factories doing more or less the same thing into industry-focused corporations after shedding their non-core businesses and services like workers' clinics and kindergartens.

There were geographically defined experimental zones, to run one pilot program or another, usually associated with more lenient policies on overseas capital, and more recently terms to attract high-level professionals from overseas.

Now, on a daily basis, the Chinese media is filled with phrases like stock market reform, medical system reform, education reform and so on, whether or not the reforms are really making headway. Some of them are seeing slow progress.

But the reason why they can be so slow is that many, if not all, of the would-be reforms are different from the reforms of the 1980s and '90s. Let's call them second-generation reforms. They are not simple, and they not just about one industry or one area any more. They all require cross-industry efforts.

They often require changing the rules in one industry while changing matching rules in others. Or it often takes a joint effort by more than one government office, or an effort to break down the boundary of bureaucratic turfs. Sometimes, the gap to cross over can be very wide.

Suzhou has a traditional culture of excellence in detail. In the reform era, it has been a trailblazer in many practices. Some of its first-generation reforms were as smooth as the silk the locals have been producing since ancient times, attracting overseas investment, building modern industrial parks and raising the city's GDP to above $20,000 per capita.

But all its past successes have only made the tasks for its second-generation reform stand out, appearing a more salient challenge.

Just one example: The city has many ancient gardens, but the reason why so many of them can be maintained is to a great extent attributable to the local garden-building craftsmanship, represented by a craftsmen's network called Xiang Shan Guild, which dates back to at least the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

There is documented evidence that Suzhou craftsmen, ancestors of the Xiang Shan Guild, played a main part in the building of the Forbidden City in Beijing, originally the Ming imperial palace. Rather sadly, however, the guild has long passed its heyday. It was disbanded in the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) but has since made a comeback, led by a few craftsmen's families compared to the 5,000 members it boasted at one time.

"My youngest apprentice is 45," says one woodcarving artist. "Younger people prefer to go to college now. If they come to our guild they have to start when they are very young, which means they can't go to college and they have to learn on a construction site - all manual work, all hard labor and all devotion for just ordinary pay."

But if the garden builders' trade (one of such high art and the philosophy it embodies) disappeared, how can the historical garden city of Suzhou keep up its charm? It can't. And if it can't, it would be both a cultural loss and an economic disaster, considering a newly rich society's rising demand for public parks and scenic areas.

A solution that is easy to think about, of course, is to move the traditional garden craftsmanship into the modern education system, to be integrated into college courses.

With its enviable fiscal power, Suzhou may well have an art institute for garden artists from all over the world, but to do so the city must go through a complex process to get approval from Ministry of Education, and perhaps also from some financial authority for its budgetary plan.

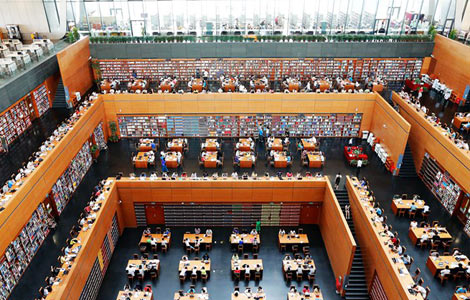

There is a Suzhou University; but Chinese colleges don't usually include such a soft interdisciplinary field combining art and craftsmanship, folk belief systems, history and cultural anthropology. If it wants to include that, probably it also needs to reconsider what to do with the administrative and financial powers of higher levels.

Suzhou is at a crossroads. To make progress would probably require a much larger reform effort than it has ever made.

To a degree, where the city stands reflects China's situation: How hard it still is to make cross-industry and interdisciplinary changes.

The author is editor-at-large of China Daily. Contact the writer at edzhang@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

The can-do generation to the fore

Riding the wave

China lists first sovereign offshore RMB bond on LSE

British PM denounces Brexit's 'complete untruths'

47% of European businesses would expand in China

Xi urges Washington to boost trust

Council of Europe unveils security convention

Former PM warns of chaos in case of Brexit

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|