To see the light, we need society's capital

Updated: 2016-04-01 08:29

By Ed Zhang(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

Keeping the middle class interested in projects at home vital to China's economic transition

It looks like 2016 will be a boring year for journalists reporting on China business. As there won't be a hard crash, what can they say about the world's second-largest economy in transition?

Perhaps, month after month, week after week, they can report only that the latest data are less than desirable, and China is still in a seemingly everlasting transition.

But investors would ask: Where is the end of this transition? There must be some signs, like some light at the end of a tunnel, of a transition that is about to move from a low-growth cycle to a high-growth cycle, mustn't there?

Just maybe, in the coming months, we'll see a new kind of competition emerge among local governments, and that may serve as an indication of China's beginning of a new growth cycle.

Investors don't like transition because it's a period of low economic growth and low yields for their money. Transition is a costly undertaking for both the government and major enterprises because there must be two different sets of outlays. There is the outlay for shutting old operations, such as closing down factories, relocating workers and selling machines to overseas buyers, and the outlay for exploring new opportunities, buying new technologies and setting up new teams.

Considering all the risks involved, either process, to dump the old or to explore the new, cannot quickly yield good returns.

The governance of the A-share market is a case in point, so is the management of many listed companies. Many reform plans have been floated, and many of them sound great. But how can they be implemented seriously in today's China? How can the regulatory officials and corporate leaders be motivated to do the right thing? No one can be sure unless people can see them not only be given orders, but also act in their own accord to do the right thing and seek the changes expected by the reform's designers.

It is precisely because transition is a costly undertaking that it is important to mobilize more money from society, rather than to just have the government print money, to pave the way for its progress.

That rich people have been diverting their savings out of the country to buy real estate and residential rights abroad, and that any slight relaxation of rules can send the housing prices in Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen skyrocketing, are enough evidence of the amount of idle money in Chinese society.

The loss in China's foreign exchange reserves was nearly $1 trillion after the domestic stock market rout in the middle of last year. Although there was no need for the government to apply exchange controls immediately, the country obviously failed to direct that amount of capital to serve China's transition and help it generate better returns.

Chinese economists keep debating how to enable the country to beat the so-called middle-income trap, or the stagnation in growth that many developing countries have experienced. But there is one common feature of the countries plagued by the middle-income trap: their continuous loss of capital and top human resources to countries where they can enjoy greater freedom and realize better uses.

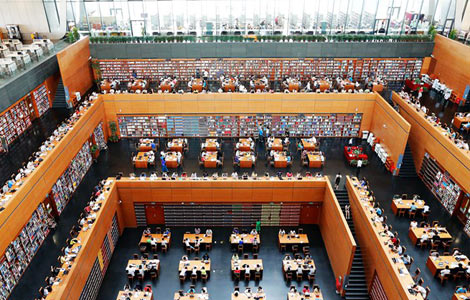

Keeping the middle class interested in opportunities in their homeland cannot be done by one, two or just a few state-level projects. To make China an interesting and potentially lucrative investment market, there is only one thing to do: enlist private capital, on a massive scale, in the building and the maintenance of many public projects.

Liu Shangxi, a senior researcher with the Ministry of Finance, defines public-private partnerships as a key reform that China must undertake.

The latest news is that, on a sporadic basis, such partnerships are being put into practice in large development projects in once-underdeveloped areas. Up to 170 billion yuan ($26.1 billion; 23.3 billion euros) from corporate and private investors is being used for the 1,500 or so kilometers of expressway now under construction in Southwest China's Guizhou province, according to the Chinese media.

Can such projects multiply nationwide? Can there be a competition among all provinces and all cities for such development? Can there be some showcase of this sort in the nation's political center of Beijing?

If the answer is no, then China won't be seeing light at the end of the tunnel. It still cannot say it has broken the middle-income trap because it still cannot mobilize its own society's potential financial power in building itself up.

And if the answer is yes, then investors may begin to see the end of the transition.

The author is editor-at-large of China Daily.

Contact the writer at edzhang@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

Inspectors to cover all of military

Britons embrace 'Super Thursday' elections

Campaign spreads Chinese cooking in the UK

Trump to aim all guns at Hillary Clinton

Labour set to take London after bitter campaign

Labour candidate favourite for London mayor

Fossil footprints bring dinosaurs to life

Buffett optimistic on China's economic transition

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|