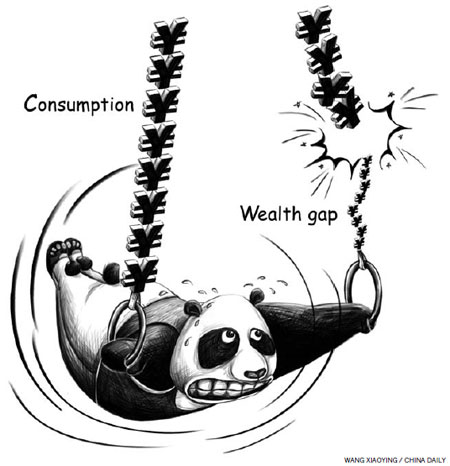

The bane of domestic consumption

Updated: 2013-01-23 07:23

By Colin Speakman (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

Retail sales in China grew 14.3 percent in 2012, ending with an encouraging year-on-year increase of 15.2 percent in December, and consumption (including government consumption) accounted for 51.8 percent of GDP.

China has also established itself as the world's largest automobile and mobile phone markets (keenly eyed by Apple, for example), and the most important luxury goods market. So one could be forgiven for thinking that 2013 will see domestic household consumption become the driver of China's growth. But will it turn out that way?

With such a large population, it only takes a small proportion of wealthy consumers to create a worthwhile market for luxury goods. However, the average income of consumers in China still remains modest - average annual urban disposable income was just 24,565 yuan ($3,947) in 2012. Income remains very unevenly distributed as China's Gini coefficient settled at 0.474 in 2012. Although down from 0.477 in 2011 and from a high of 0.491 in 2008, it is still well above the 0.4 mark that is seen as unacceptably skewed toward the minority, that is, rich people.

The power of the affluent to spend on luxury goods was illustrated by last year's spending spree of Chinese consumers traveling abroad. In 2012, China's luxury goods consumption reached $46 billion, of which $27.1 billion was spent overseas, a large percentage of which can be potentially diverted to the domestic market. But that would require reductions in the tax on luxury goods in China and the development of more recognized Chinese brands - a process which will take time.

Indeed, it is likely that an increase in consumption among ordinary people will also take time. Domestic household consumption (excluding government expenditure) remains stubbornly below 40 percent of income, whereas in most major economies it is around 75 percent and sometimes higher.

The low percentage of household spending out of income is explained by a continuing desire to save for unexpected events that are not covered in other ways. The authorities have to improve the social security net for medical care, job loss and retirement if the average consumer is to risk depleting his/her savings by higher consumption.

In Western economies, the rainy day provision often comes from access to credit from unused credit card balances or equity withdrawal from housing assets. We know the dangers that uncontrolled access to credit can bring in the West, yet we see increasing marketing of credit cards in China to the younger generation. Caution is urged here.

Exports account for roughly one-third of China's GDP and they remain an uncertain future contributor given the weaknesses in Western economies. However, it would be difficult to see domestic consumption growing fast enough in the short term to compensate for any significant decline in export demand.

Hence, China faces a difficult balancing act in transition. It remains important, in an era of apparently lower economic growth, to hold on to modestly paid jobs in the export sector where labor costs and controlling any significant appreciation of the yuan remain key factors. If that is not done, multinationals will increasingly look to countries like Cambodia, Laos, Indonesia and Vietnam for lower costs. Yet, if more demand can be internalized within China, it would increase household income from employment in higher added value industries and the resulting higher incomes would help consumers to afford higher priced products - a virtuous cycle.

It makes more sense for China to increase consumer spending in the general market (as opposed to just the high-end market) to raise the living standards of the majority of workers.

With many workers still surviving on modest incomes, is relying on rising luxury goods' markets really the only acceptable way forward? Even though a car often seems a necessity in Western economies and car ownership is low per head in China, can Chinese cities really go on absorbing more cars every year and deal with the associated congestion and pollution?

The behavior of the housing market is likely to be a factor in consumer spending in 2013. While measures to make housing more affordable are sensible, the recent evidence of modest increases in housing prices in many cities is not necessarily bad. Few people want to buy a house if they think housing prices could fall later, and a modest upturn is desirable and more home purchases will underpin a general rise in consumer spending. All in all, the Year of the Snake will be an important transitional year for the Chinese economy.

The author is an economist and director of China Programs at CAPA International Education, a US-UK based organization that cooperates with Capital Normal University and Shanghai international Studies University.

(China Daily 01/23/2013 page9)

Today's Top News

Police continue manhunt for 2nd bombing suspect

H7N9 flu transmission studied

8% growth predicted for Q2

Nuke reactor gets foreign contract

First couple on Time's list of most influential

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|