Darker clouds over world trade

Updated: 2011-12-13 07:09

By Dan Steinbock (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

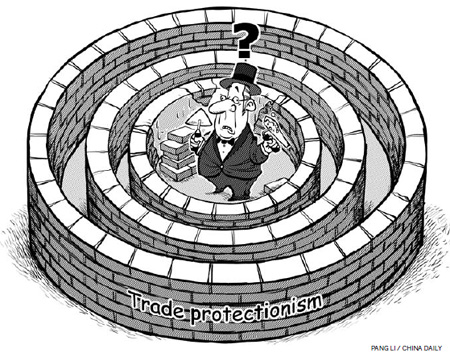

Rising trade protectionist measures adopted by some countries could spell trouble for China, which has just completed its 10th year as a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO).

In 2010, world trade recorded its largest annual increase as merchandise exports surged 14.5 percent, supported by a 3.6 percent recovery in global output as measured by GDP. China made a particularly strong contribution to the recovery of world trade, with its exports increasing by a massive 28 percent in terms of volume and its imports rising by more than 22 percent.

The rebound was strong enough for world exports to recover its peak level of 2008, but not strong enough to return to the previous growth path. On one hand, the debt crises in major developed nations, especially the European Union and the United States, continue to reduce global demand. On the other, as trade ministers are about to meet at the WTO ministerial conference from Dec 15 to 17 in Geneva, world trade is expected to grow in 2011 by 6.5 percent and rising trade protectionism spells trouble.

According to the recent global trade alert report, unexpectedly adverse macroeconomics in 2011, combined with election cycles, has weakened the resolve against protectionism. China, along with some other countries, remains the most frequent target of crisis-era protectionism.

Other WTO members have used anti-dumping cases to target China's trade policies. Such cases will remain a convenient tactic as long as China is considered a "non-market" economy under the terms negotiated with the WTO in 2001 (the clause will expire only in 2016). To build a case, these terms allow a country to substitute China's prices with those of another, often pricier, market economy.

In the next half decade, the "rules of the game" at the WTO may shift. According to a recent WTO decision, state involvement must be accounted for in bank financing, land prices and production input prices. In other words, the anti-dumping tactic is being extended to anti-subsidy cases by using higher third country market rates and prices to demonstrate subsidized pricing.

For all practical purposes, the disputes are now being taken to a different level. It is one thing to say, "since I do not like your trade policy, you better change it", and quite another to say, "since I don't like your system, change it".

In brief, trade pressure is converted into systemic pressure. The anti-subsidy retaliation game has already begun. It is taking place in the emerging industries of the future - the clean technology.

The push toward the "green sector" began after the oil crises of the 1970s. In the past three decades, leadership in the key segments has shifted from Japanese to European to American and, most recently, to Chinese companies.

In early November, the US government launched an investigation into imports of Chinese solar panels after American solar companies called for anti-dumping and anti-subsidy duties. In return, China's commerce ministry said it was looking into US renewable energy subsidies.

The White House used to enthusiastically promote Solyndra, a manufacturer of solar power equipment, until plummeting silicon prices led the company to bankruptcy in September. The Republicans targeted the case as an example of US President Barack Obama's "industrial policies". In turn, the White House is now criticizing China's "industrial policies". This political tit-for-tat in and around the anti-subsidy cases is useful in the election year in the US.

Since progress in the multilateral Doha initiative has been slow, many countries are now promoting regionalism to revitalize trade liberalization, but in exclusionary terms. For instance, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), supported by Washington, would exclude China - a vital Pacific power and the world's largest exporter whose trade may be nearly one-and-half times that of the United States by 2020.

Trade friction is likely to increase because of the debt crises in the developed economies and growth pains in emerging economies. The developed economies will be tempted to use trade rules differently to make China and other large emerging economies the scapegoats. It is like saying: "Look, our debt crisis is not our problem. They evolved with the rise of China, India and the rest. So it is their fault, not ours."

The very success of China and other emerging economies, which follow its trajectory, is an inadvertent contributing factor in the WTO friction. In the past decade, the priority for China was to liberalize the market to support industrialization and urbanization. This priority remains central to the less developed provinces and cities. In top-tier Chinese cities, however, the priority is to boost competitiveness by moving up the industrial value chain. This is hardly news, though. After World War II, Western Europe, too, liberalized markets at first and began to move higher in the value-added chain only later. The goal was to catch up with the US' level of economic development to provide better living standards - and so do China, India, Brazil, Russia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and other emerging and developing countries today.

In the 10th year of China's accession to the WTO, rising trade protectionism holds potential for trouble and could lead to more friction in world trade. And if it harms China's growth it will also harm the growth of other nations - including the advanced economies.

The author is research director of international business at India, China and America Institute, an independent think tank in the US and visiting fellow at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China).

(China Daily 12/13/2011 page9)