Private classes far from home

Updated: 2013-09-29 07:15

By Sun Ye and Erik Nilsson (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

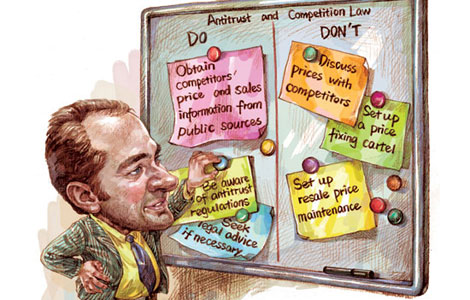

Melinda Howe's four children conduct their classes in various venues. Biology lessons are given at gardens (above), while reading is done at home (left). Photos Provided to China Daily |

While home schooling remains rare among the Chinese, Westerners living in the country are seemingly more likely to educate their children themselves than they are in their homelands. Sun Ye and Erik Nilsson study the phenomenon.

Judy Rodriguez came to China as an educator. One part of her life as an instructor in Beijing is spent at the suburban New Generation Foreign Language Library her family founded. The other is as her daughter Abby's sole instructor at home.

The 12-year-old hasn't attended school as a student in the five years since the family moved to China. Her mother has spent those years teaching others in classrooms - time during which Abby studies independently.

The 54-year-old American draws from her pedagogical philosophy as an educationalist in her decision to teach her daughter outside official school systems. Yet many expatriate parents turn to home schooling solely to navigate obstacles to educating their children in China.

While such obstacles aren't the only reasons for Judy's decision, they're major influences, she says.

International schools in 2011 averaged nearly $33,000 a year - a 10 percent increase over the previous year, expatriate magazine BeijingKids reports. Language barriers - the older the child, the less penetrable they are - exclude most foreign children from most local schools. And policy restrictions determine which schools foreigners can attend.

It was international schools' excessive price tags that motivated American Melinda Howe to home-school her three girls - two of whom are adopted from China - and her son. Her youngest is in first grade and the oldest is in sixth grade.

"We feel getting used to both the language and the system (would be) too much for them," the 44-year-old mother says.

And it wouldn't be worth it if the family returned to the United States. She believes the local education system focuses on "too much memorizing".

While no reliable figures exist for expats who home-school in China, cost and accessibility seem to point to a greater likelihood they'll do so here than in their homelands.

The US government's National Center for Education Statistics' 2007 figures say about 1.5 million American children - roughly 5 percent of the school-age population - were home-schooled then.

About 0.01 percent of Chinese children were home-schooled in 2013, the 21st Century Education Research Institute reports. But domestic home-schoolers are a growing group, the institute says.

Because Western home schooling is an entrenched tradition and more advanced - the new practice hovers in a legal gray area in China - accredited Western school curriculums are easily available on multimedia platforms.

While the depravation of other options in China forces many foreigners into home schooling, they often discover unanticipated boons.

Most say the greatest advantage is flexibility, especially in terms of time.

Melinda's children can start their study quotas as early as 7 am if they choose.

"If they finish early, they can end class early," she says.

The mother says home schooling in this way also teachers her kids time-management and self-control.

"(Abby) is very self-reliant and independent," Judy says.

She gets up on her own at 7 am to head to the library, where she plays with other children visitors and studies Chinese with a tutor.

Upon returning home, she spends two or three hours using the Switched-on School House computer program.

Home schooling's flexibility means Abby has time to take her grandfather grocery shopping and hang out with library patrons.

"She comes to me if there is a problem," the mother says.

"Going to a normal school means a lot of wasted hours like getting from one place to another and waiting for the whole class to follow through."

Commutes often exacerbate foreign parents' exclusion from China's education.

The Howe family, for instance, lives in Beijing's relatively remote yet extremely affluent suburban expat hub, Shunyi. That distance excludes the family from joining the home-school cooperatives popular among locals.

"But we have a backyard where they can do all sorts of things," Melinda says.

She says such time flexibility extends beyond daily classes. They can also decide their holiday schedule and vacations.

Her 11-year-old sixth grader Riley is an advanced learner who could finish a day's work by 1 pm and 1.5 years worth of work in a year, the mother says.

"Working closely with your children also lets you find out their strengths fast," Melinda says. "We can adjust to their individual likes and find what fits them best. That's impossible in an ordinary school."

Melinda doesn't stand in front of her kids during classes. She works alongside them.

The mom helps with the math problems they find on Ixl.com and their reading exercises.

They sometimes do biology and drawing lessons at the Beijing Botanical Garden.

She believes one of home schooling's greatest advantages is the quality time she spends with her kids while still working part time.

"I'm blessed to be able to stay this long with my kids," she says.

But they remain social.

Their church offers such group activities as Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts.

"And the four of them are already a small group," the mother says. "They learn to help and share with each other."

While Abby is the only child in her class, her mother doesn't believe home schooling has stunted her peer engagement.

"There are no socialization issues," Judy says. "She learns a lot from real life."

So do home schooling parents.

Melinda says teaching four children at once isn't easy.

"When you are parent, you ask for the best from a teacher - and now you're responsible for it," she says. "As any parent would say, you want them to have the best."

Judy says acting as her child's primary educator enables her to provide better moral instruction.

"I grew up learning so much more from my family and life than in a school," she explains.

"I want my children to learn a variety of things and learn the way it suits her, too. I could put (Abby) in a much more strenuous academic curriculum, but that's not what I aim for.

"I'd rather she be happy with what she learns and keeps going on."

Contact the writers at sunye@chinadaily.com.cn and erik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 09/29/2013 page4)

Today's Top News

UN's Syria resolution on point, FM says

China won't seek hegemony, FM tells UN

7.2-magnitude quake hits S, SW Pakistan

Obama, Iran's Rouhani hold historic phone call

UN votes to eliminate Syria's chemical weapons

'EU signal needed' for investment

China to pursue peaceful rise

FTZ to define development

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|