Mark my words

Updated: 2013-06-01 08:14

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

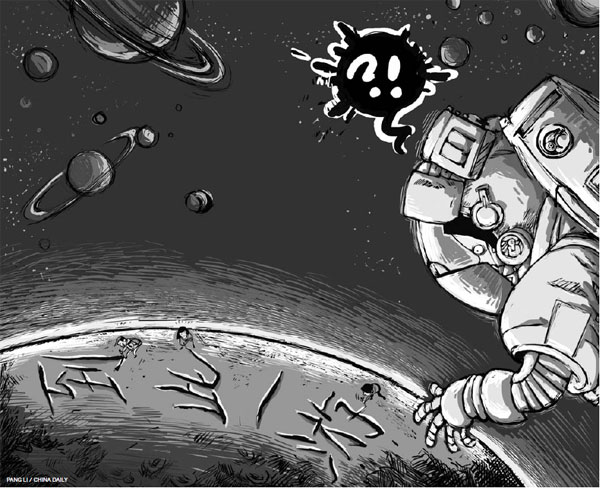

Some Chinese have the antiquated notion that carving their names in historical sites can make them immortal, but with new technologies it may bring them notoriety. Eradicating such behavior, however, will take a change of national mindset.

A recent photo from a temple in Luxor, Egypt, has shocked China. Inscribed in Chinese on a 3,500-year-old stone is: "Ding Jinhao was here."

The photo was taken by a Chinese tourist who, with his fellow travelers, was so ashamed at the defacement of an ancient relic by a countryman that they tried to erase it. Failing that, he posted the photo on the Internet, triggering a nationwide wave of revulsion over the act.

Soon, the violator's parents came forward and apologized for their 13-year-old son, who they said cried all night long - over what he did or over his instant infamy, is not clear. As Ding is underage, talk of legal action has come to an end and his crude handiwork has since been successfully removed.

Ding is just one of millions of Chinese with a penchant for carving their names on places and objects of historical or cultural interest. Take a look at any section of the Great Wall and you'll understand the magnitude of the problem. On some busy parts of the Wall every brick is crammed with signatures.

If you have to blame this on one person, it must be Sun Wukong, aka the Monkey King. In the classic novel Journey to the West, written in the 16th century, the mischievous monkey leaps into the sky to prove his ability to cross thousands of miles in one jump. At some faraway location he carves his name to prove his presence.

Upon hearing of the monkey's feat, the Buddha shows his hand - and there is the naughty animal's inscription, "Wukong was here" - showing that the vast space covered by the monkey was but an inch on the Buddha's palm.

Since then, it appears that defacing famous property has been a favorite pastime of some Chinese. One can equate it with vandalism, but it may not occur to the perpetrators that they are damaging something they do not own.

Graffiti may be a better term. Like a graffiti artist in a Western country, a Chinese inscriber such as Ding essentially sees his name as a worthy addition to an existing statue or noted structure, regardless of what others may feel about it.

There are differences of course. Graffiti appear mostly on walls with little historical value, and vary in content; the engravings of Chinese tourists can appear on anything and tend only to record names, sometimes followed by "was here", "loves so-and-so" or "such-and such rules" - in other words, it's more childish than most graffiti.

I've never talked to graffiti artists, so I don't know how much hope they harbor about leaving an imprint in the annals of history. But most engravers, I believe, are under the mistaken impression, even subconsciously, that whatever they carve in stone or bronze work, or on tree trunks, will last forever and be studied by future anthropologists.

This exaggerated sense of legacy haunts many in China, celebrities and riffraff alike. They believe that life is ephemeral and that one's presence in a certain place, especially one of historical significance, has to be recorded with something tangible.

I thought the ubiquity of digital cameras had put an end to that, but no. Still, I have a hunch that cameras have alleviated the plague of such scrawlers, scrapers and scribblers.

No sooner had Ding been exposed, than another brazen embellisher is brought to light: "Song Yin, a senior reporter with a Hong Kong newspaper, visited this place."

Now, this is more puzzling. As a reporter with bylines, this guy does not lack seeing his name in print, and as an adult, he should know that scratching a mural in the Dunhuang Grottoes - the mural dates back to the Western Xia Dynasty (1038-1227) - is a very serious violation.

Song left not only his name and title, but also the date of his inscription, as if he were eagerly begged to bestow an honor on the mural. Smart criminals may leave behind teasing morsels of clues, but not even an idiotic one would leave their autograph - unless they felt proud about it.

In a sense it is in the Chinese cultural genes to "riff off" an artifact, so to speak. Ancient officials and literati would feel obliged to write a couplet or two when they felt inspired by a natural scene or a man-made wonder. You may encounter pavilions or mountainsides etched with such words, which now evoke wows of appreciation.

Less conventionally, an old scroll painting is often covered with calligraphy from later generations, who obviously did not have any qualms about adding to what they regarded as precious gems.

From a purely artistic perspective, many of the ancient inscriptions added to earlier creations were written by great wordsmiths with a flair for bon mots or calligraphy. They now seem to merge seamlessly into an organic whole. None of them simply scribbled "Here I am!" in poor penmanship.

However, it is time we cut this age-old tradition, which is still being carried on in respectable circles with, for example, requests for inscriptions by glitterati, especially officials. If it involves only paper and ink, there's no problem, but what if the inscriptions end up in public places?

There have been government efforts to tone down such ill-suited flourishes of personal expression. But a cultural change takes more than government decrees. What if an eminent scholar is asked to imprint something meaningful on a sculpture in a public park? Does it matter if the park is new or a heritage site? Or if the inscriber has good or bad calligraphy? What if the sculpture is a cultural relic but privately owned?

And who is to judge that a famous writer's couplet will be more historically noteworthy than an ordinary person's doodling? The cave paintings of thousands of years ago were not engraved by great artists, yet they have a value of their own. Scrutinized thousands of years from now, would the scratching of names at tourist destinations take on an elevated meaning?

I'm not justifying what Ding and Song did. There's no way one can put a positive spin on their acts. Even if they did not inscribe on priceless antiques but, say, on new works with little value, their words are distractions that mar the integrity of the works. To show off their traveling credentials, they should have sent postcards or, more fashionably, uploaded instant photos for all the world to see.

Obviously some people are more acutely aware of the pitfalls of this Chinese custom. I asked a friend of mine to provide a blurb for my new book, and he turned me down, saying: "Your book should have nothing but your words in it. My name or anyone else's will only spoil it."

I thought he was unwilling to lend his gravitas, but now I understand. Still, my publisher wants the cover to be full of celebrity endorsements. That's what everyone does; that's how books stand out on a shelf.

We should respect the integrity of a piece of art, and channel our urge to leave an indelible mark at a place of historic interest into creating an independent piece of art, such as a great photograph or a memorable travelogue.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 06/01/2013 page11)

Today's Top News

Chinese president arrives in Mexico for state visit

EU imposes duties on solar products

China is victim of hacking attacks

Police advise women to 'cover up'

Beijing to have more clean-energy taxis

Author's widow claims court victory

Rape suspect appears in HK court

China's water quality 'not optimistic'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|