Standing debate

Updated: 2013-01-26 08:21

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

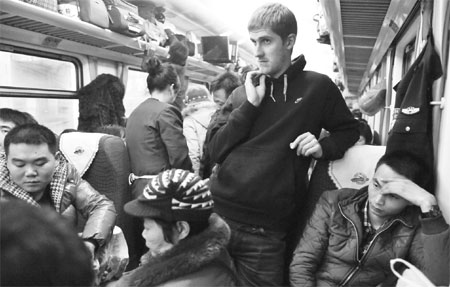

A foreign passenger finds himself in a packed train before last year's Spring Festival. Deng Xiaowei / China Photo Press |

The pricing for train tickets with no seats is fundamentally an economic issue, but in China it inexorably turns into an argument about social equality.

The loudest sound emerging from the ruckus that is the biggest human migration in the world is a call to reduce the cost for standing.

Chunyun, aka China's annual year-end rush to celebrate the Spring Festival, will last 40 days and register a total of 3.4 billion trips this year. (The number has been growing steadily year by year.) Railroads will account for two-thirds of the trips, which means resources will be stretched almost to breaking point.

What prevents it from breaking - or rather, what makes it possible to move so many people home for the Chinese New Year and then back to where they work - is standing room.

A carriage designed to take 100 passengers is sometimes packed with 300.

Since most are long-distance trips, you can imagine the discomfort and misery of riding in such a cramped space. The only comfort, if it can be so called, is to know that you won't be put on the roof of the train or dangle from the door, which seems to be the case in some Southeast Asian nations, at least as illustrated in photos posted by comparison-prone netizens.

But you may need to lie under the seat, behind a row of legs, or be jammed in the toilet, or even up on the luggage rack. Having space to plant your feet on the floor is a relative luxury.

Yet, for that "privilege", you'll have to pay the same price as the guy guaranteed a seat.

Is that fair? As regular Chinese trains have three classes - hard seat, hard berth and soft berth - and are priced according to the level of comfort, shouldn't standing be cheaper than a hard seat, the least-expensive ticket under the current pricing scheme?

Those who take high-speed trains (trains with the initials D or G) do not need to worry about it. The railway department does not sell standing tickets. And they don't need to. The capacity for lines served by bullet trains is so high that tickets are readily available even for peak travel days - for a much higher price, of course, with first-class seats on par with an air ticket.

Unfortunately, China's network of high-speed railroads is still a work in progress. The completed lines serve mostly the coastal areas while a typical chunyun passenger is a migrant worker who leaves a coastal city for his hinterland home. If, for example, you want to go from Guangzhou to Chongqing a week before the Chinese New Year, you'll be considered lucky to get a standing ticket.

The half-price movement has gathered momentum online and has been widely reported by the traditional media. A survey conducted by Beijing News shows 91 percent of respondents favor such a discount while less than 5 percent oppose it. Of those who support the call, 42 percent argue for a 50-percent or more cut while the rest endorse a smaller reduction.

The railway department, in reluctant response, said it is not feasible. What if a passenger with a seat leaves at the next station and the guy standing next to him gets it for the rest of the journey? How do you calculate for such seating and standing permutations?

Others propose that a few standing-room-only cars be reserved so that standing passengers won't mingle in the seating area. But wouldn't that mean a colossal waste of space desperately needed during this holiday season?

From an economic point of view, it is not that standing tickets are too expensive, but, rather, the regular tickets have fallen far behind the rate of inflation. Train tickets rose a couple of times a dozen years ago when train speeds were increased.

What was considered outrageous a decade ago is bargain-basement nowadays. A taxi ride across town can cost 100 yuan, but a 40-hour train ride from Beijing to the Sichuan-Yunnan border on a hard berth is less than 1,000 yuan.

In the current climate of populism, it is a cardinal sin to say a train ticket is too cheap. But if you compare it with other products and services, it is one of the few things that has stagnated, except for the high-speed lines, that is. I have the strong feeling that train tickets are like laws: Once they're set you cannot change them incrementally, so a high price is set in advance to anticipate a decade of declining profit margins.

However, the railway department does not have too much leeway in setting prices. As it is a State monopoly, it has to take on certain responsibilities that fall on the shoulders of government agencies.

The chunyun traffic is not price elastic, meaning people have to make their trips regardless of the price. Raising prices will not ease the jam, but will create more social inequity as the pressure is felt most acutely by the low-income demographics.

Likewise, lowering prices for standing tickets is reasonable mostly in the context of social fairness and income redistribution. As public transport in Chinese cities is heavily subsidized, with the benefits going mostly to middle- and-low-income brackets, the same idea seems to apply to long-distance travel.

But we have to weigh both the pros and cons before jumping to conclusions. In China, prices are more often artificially high, such as for performing arts and certain entertainment venues.

Artificially low prices, such as on Beijing's subway, amount to a systematic subsidy. But if overused, they can stymie normal economic activities. If the government essentially gives something away, there is no way an alternative service offered by a business can compete.

It is understandable people want low prices. That's human nature. But don't forget, government subsidies come from taxpayers. So, the right question is, is this the best use for a subsidy? Of course, if you compare it with government waste or corruption, this is much more worthwhile. But what if you have to choose between writing off a chunk of railway travel and funding for educating poverty-stricken children?

China has been developing a market economy for three decades now, and we have moved from an era of scarcity to one of abundance - for most products and services. As we plunge deeper into the free market, a feeling of nostalgia has re-emerged. Looking at the dizzying choices and stratospheric prices, people may be enticed by the old ways of fixed but low prices - never mind that it inevitably leads to undersupply and long lines.

The right approach, as I see it, is to increase capacity while at the same time maintain a reasonable range of options. Building high-speed lines is the ultimate solution to easing the chunyun traffic. But low-priced services should not be totally eliminated. They cater to those with different purchasing power - and those who value time differently. When there are choices, people will divert their energy to researching the options rather than criticizing the lack of price differential for sitting and standing tickets.

Subsidized pricing is not a silver bullet; instead, it could be a wolf in sheep's skin.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 01/26/2013 page11)

Today's Top News

Police continue manhunt for 2nd bombing suspect

H7N9 flu transmission studied

8% growth predicted for Q2

Nuke reactor gets foreign contract

First couple on Time's list of most influential

'Green' awareness levels drop in Beijing

Palace Museum spruces up

Trading channels 'need to broaden'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|