In with the old

Updated: 2012-07-16 09:49

By Liu Xiangrui and Dachiong (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Gandan Monastery is one of the six major Gelugpa Sect monasteries in the Tibet autonomous region. Photos by Dachiong / China Daily |

|

|

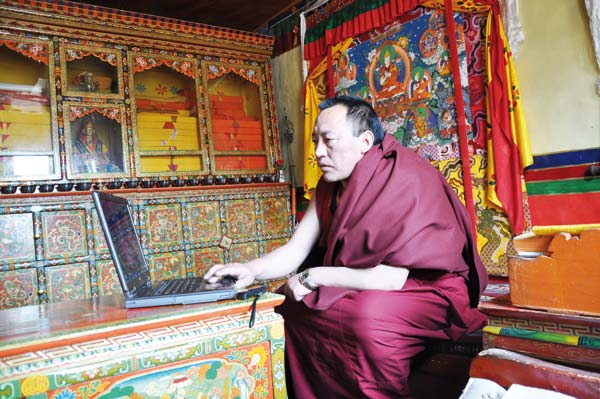

Gandan monk Nagwangtanjong uses a computer in his room at the monastery. |

Related: Samye Monastery reborn

The 600-year-old Gandan Monastery near Lhasa is thriving with the help of modern conveniences and technology. Liu Xiangrui and Dachiong report in Lhasa.

Sitting on a hilltop at an altitude of 3,800 meters, 57 km east of Lhasa, Gandan Monastery looks splendid, with its towering buildings of bright red and white. Built six centuries ago by Tsongkhapa, founder of the Gelugpa, or Yellow Hat Sect, tradition and modernity creates a satisfying life for monks here.

Scripture study, an important Tibetan Buddhist practice, is one of the traditions that continues to thrive.

Gandan Monastery in Tibet autonomous region has two Dratsangs, or Buddhist colleges, and its 143 monks are divided into classes of different levels.

For two consecutive years, monks here have won first place in the annual test for the Geshe Lharampa degree, which represents the highest level of attainment for monks studying the scriptures.

Lhosanglungrig, 35, recalls with pride the moment when he won first place in 2011. Since he arrived in Gandan Monastery at 11, he has studied scriptures with two famous mentors.

"Yet, I'm still an ordinary monk. The study of Buddhadharma is a lifelong journey. It's as boundless as an ocean," repeats the monk, sitting on his bed and turning his prayer beads continuously with his hands.

He smiles occasionally and talks in a low voice. A small desk beside him is piled with scripture books.

For Lhosanglungrig, who still attends daily scripture classes, the only change in his life since winning the Geshe Lharampa test is studying more esoteric Buddhist theories.

Yet Lhosanglungrig and his parents are satisfied. According to tradition they offered sacrifices and donations to the monastery to give thanks for his attainment.

"My parents gave me life and a lot of other things, I'm just repaying a debt of gratitude to them with my hard work over the years," Lhosanglungrig explains. "If their devotion to me is a snow mountain, what I have repaid is as insignificant as a snowflake."

Improved conditions in the monastery have enhanced his life, and facilitated his scripture studies, Lhosanglungrig says.

"Several years ago we had to study under oil lamps at night, and the dim light harmed our eyes. Now we have electric lights," he explains.

In 2007, tap water was piped in. Before that, monks had to fetch water from the other side of the mountain, a journey that took over an hour.

The monastery's new library also excites Lhosanglungrig.

"I don't have plenty of money and was often caught up in financial problems when I had to buy scripture books that were not part of the monastery's old collection," he says.

At the same time, modern technology has enhanced his life.

TVs, radios, phones and computers have bridged the link between monasteries and the outside world, says Nagwangtanjong, a 41-year-old monk in Gandan.

Nagwangtanjong's room has shining Buddha statues in a colorful cabinet, tangkas on the wall, hand-woven cushions and traditionally painted wooden furniture.

There is also a refrigerator, a water dispenser, a TV set, a radio, and his laptop computer on the delicately decorated table.

"I had never used a computer. Then I taught myself to use it," Nagwangtanjong says. "For me, it's both magic and useful."

Nagwangtanjong took his computer with him during his stay in Japan, in 2008, when he was invited to preach sutras at Japan's Jambalin Monastery.

Nagwangtanjong is reluctant to use the device to surf the Internet and communicate with people all over the world for fear of affecting his Buddhist studies.

However, besides storing a long list of scripture files and making notes, he has also compiled a draft book of roughly 100,000 Tibetan words about Gandan Monastery's history. Nagwangtanjong plans to publish it in both Chinese and Tibetan, as a scholar has already volunteered to translate it into Chinese.

As a member of the monastery's management committee, Nagwangtanjong has made the most of his spare time to study Buddhist scripture.

He has applied to study at the High-level Tibetan Buddhism College of China in Beijing and wants to become an outstanding monk.

"I am confident of passing the examinations," Nagwangtanjong says, smiling.

Contact the writers at liuxiangrui@chinadaily.com.cn.

Related Stories

Just when you got digital technology, film is back 2012-07-15 14:13

A unique calling 2012-07-13 13:31

Tibetan folk festival 2012-07-10 10:31

Magnificent scenery in Tibet's Nagqu 2012-07-06 17:19

Tibetan farmers celebrate Ongkor Festival 2012-07-06 15:25

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|