Weird and wonderful world

Updated: 2012-05-04 09:23

By Wen Chihua (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

The scene is bizarre: goblin-like bronze sculptures with human faces but no torsos sport demon wings and shoes - and sometimes two heads, one of which protrudes from the tips of their tails.

Distorted? Indeed.

Demonic? Perhaps.

Whimsical, festive and fun? Definitely.

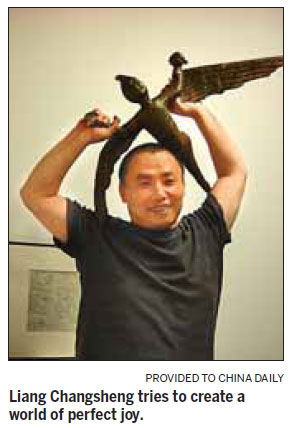

"That's the point I want to make in my works - no torso, no desire," the figures' creator Liang Changsheng says at the group exhibition The Adventures of the Three Loafers in Beijing.

"And if there's no desire, there's no conflict. And if there's no conflict, there's no violence."

Liang believes the torso is the seat of men's lust for sex and food.

"Those two things are the root of all evil," he says.

So, his humanoid bronze sculptures, paper-cuttings and drawings create a "visionary utopia" he calls "He Le" - "Harmonious and Happy". It's meant to represent a world of perfect joy.

This intimate realm has many unique features. Hierarchy disappears. The demonic-looking humanoids are free of corporeal form. They live in peace and harmony, frolicking, flirting and flying as they please.

Unlike many contemporary Chinese artists, who have relegated their subject matters to political icons or symbolism that appeals to Western galleries, Liang has long remained fascinated by Buddhist iconography, Chinese painting and such folk art traditions as paper-cuttings.

The energy of Liang's vision was incubated during his early engagement with paper-cut practices. He often combines such traditional motifs as Buddhist figures and phallic iconography, and magic subjects - like flying animals and dancing parrot heads with women's legs crossing over a man with spread legs.

So, his modus operandi is more deeply seated in contemporary Surrealism's grotesque forms.

The most provocative piece among Liang's paper-cuts is An Auspicious Rooster and a Woman.

It depicts a riotous rooster with a long neck and strong, man-like legs, with fresh lotus in its mouth. The fowl is perched atop a voluptuous naked vixen, who lies on the grass, smiling invitingly and seductively.

Liang's early idiosyncratic paper-cuts were so impressive that he was accepted by the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing in 1994.

In 2002, he started a series of panoramic paper-cut vistas portraying his He Le world. One piece creates a utopia crowded with half-human, half-beast figures. They dance on rocks, meditate on floating clouds and perform acrobatics on raging rivers.

Canine-like creatures with human faces are arranged on the bottom right and left. They ride human heads to watch the more humanoid characters frolic.

The composition of this massive paper-cut is so well integrated that it looks like a painting.

Deformed characters also inhabit in Liang's ink drawings.

In his tapestry-like long scrolls, entitled The Blissful Life in Paradise, Liang continues to allow his inclination toward Buddhist figures to co-exist with bizarre humanlike beasts.

He sets up a scenario in which sacred Buddhas and secular bodies are juxtaposed, while sexuality and spirituality abruptly jut into the fore. The Buddhas sit against traditional landscapes to watch over unholy fiends, whose spirituality is wretched. The scene is equal parts disturbing and jubilant - it's as joyful as a carnival, in fact.

People's Fine Arts Publishing House critic Han Yazhou says the work shows "a naughty charm that's satirical of humankind and mercy. But there's no evil or depravity." What makes Liang's art extraordinary is that his imagined He Le world is Surrealist and Realistic, obscure and clear, and honest and self-deceptive.

"That can be read as an evocative interpretation of the dark side of ourselves and today's insane society," Han says.

"People get lost in their pursuit of the material, and their corporeal and spiritual lives seriously collide, like animal and human forms in Liang's works."

But Liang says his He Le world is more about his personal salvation than social commentary. Liang's fantastical imagery comes from his larger-than-life childhood dreams, in which the impossible became possible and real.

"I started to have these dreams when I was about 4 or 5," he says.

"In them, men can freely transform into any form - birds or beasts, angels or devils - as they like. These visions are such an eternal joy they are impossible in the chaos of grim reality."

He found himself increasingly depressed every time he awoke, because he didn't have any way to realize these blissful dreams.

Liang says he "deliberately hides his critical stance on society in a carnival-like scenario that mirrors a part of our own disguised lives. Anxiety and conflicts are tactfully veiled behind a surface of brightness and light-heartedness."

Related Stories

Vivid paper sculptures 2012-03-28 09:29

Shaping concepts 2012-03-25 11:26

'City of ice' shines in frigid winter with snow sculptures 2012-01-30 17:07

Snow sculpture contest begins in Harbin 2012-01-11 11:18

Ice sculpture competition in Harbin 2012-01-08 15:26

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|