Out of breath and running out of time

Updated: 2012-02-02 16:20

By Liu Zhihua (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

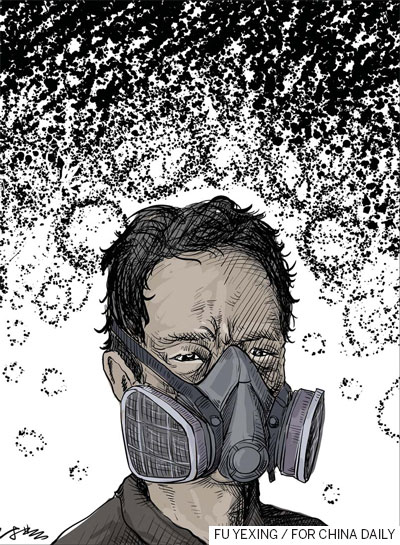

Those suffering from the work-related lung illness pneumoconiosis are hoping new regulations will provide some relief. Liu Zhihua reports.

For Lu Quanjun, an amendment to the Law on Occupational Illness Prevention and Control offers a ray of hope.

The 38-year-old was formerly a mineworker in Dabao village in Hanyuan county, Sichuan province, and has suffered from pneumoconiosis for about 10 years.

According to the amendment, which recently took effect, the application process for diagnosis, treatment and compensation of occupational illnesses has been streamlined, while local governments are tasked with providing financial aid to those who cannot secure compensation from their employers.

"I hope the new regulations will bring about change," Lu says. "The cost of treatment is a bottomless pit, and we are struggling to live."

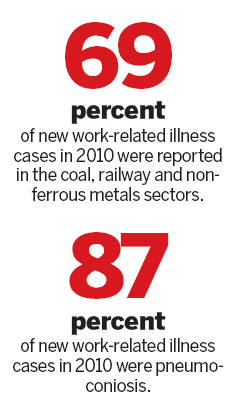

According to the Ministry of Health, there were more than 27,000 new work-related illness cases in 2010, among which, about 69 percent were reported in the coal, railway and nonferrous metals sectors, and 87 percent were pneumoconiosis.

In the eight villages neighboring Lu's hometown, 30 people have died from pneumoconiosis in the past few years. About 120 former mineworkers in the villages are pneumoconiosis patients, and 28 are suffering from severe symptoms and will "likely die within a few years", Lu says.

When Lu started work at a lead and zinc mine in 1989, he thought he was lucky to find a well-paid job. But he was unaware that years of breathing in particulates created by drilling and explosions could make him terminally ill.

In 2000, word spread in Lu's village that some miners had contracted pneumoconiosis. A fearful Lu went to the hospital because he had frequent tightness of the chest, shortness of breath and dizziness. He sometimes coughed up blood.

Even after the doctor confirmed he had pneumoconiosis, Lu was unsure how this would affect him.

Pneumoconiosis encompasses a wide range of industrial diseases caused by the inhalation of dust.

"The disease develops without any obvious symptoms at first," says Zhao Qingqiong, an occupational disease specialist at the Central Hospital of Tongchuan City Mining Bureau in Shaanxi province.

"When symptoms, such as a cough and tightness of the chest, occur the situation has become very serious," Zhao adds.

When dust builds up and is retained in the alveoli of the lungs, it causes an inflammation, which can turn the normally elastic lung wall into fibrous scar tissue and make the lung lose elasticity and function.

"It is like if there is a thorn stuck in your thumb, it will make the skin around it abnormal and hard," Zhao explains.

Zhu Qishang, director of the occupational diseases department of West China Hospital of Sichuan University in Sichuan's provincial capital Chengdu, says, "Usually, after five to 10 years of dust exposure, an X-ray will show shadows in the lungs of most people. Once fibrosis starts, it is like getting on an accelerating train and will never stop."

Zhu says workers in dust-rich environments are most at risk of developing the disease. Most of her patients are migrant workers, who get the disease due to a lack of protection in the workplace.

"If enough protection is provided, the chance of getting the disease will be sharply reduced," Zhu says.

"The problem is that migrant workers at small and private factories or mines do not know about protection or do not have the power to demand it. Once they get the disease, the time interval between the appearance of symptoms and the start of fibrosis makes it very difficult for them to get timely treatment and compensation from employers."

Feng Zhaoping, 45, from Majiadu town in Zhushan county, Shiyan city, Hubei province, is one of those workers who contracted the disease but failed to get compensation from his employer.

Introduced by a friend, he started to work at Hubei Silver Mine in 1999. His work was drilling underground, and his salary increased from 1,000 yuan ($159) a month in 1999 to 2,000 yuan in 2002.

Yet, in early 2004, Feng was dismissed.

He went to hospital in September 2004 when a cold developed into a serious cough. He had a tight chest and overwhelming fatigue. He was later diagnosed with pneumoconiosis.

Feng says he managed to get his health check results from 2002, which the mine owners had concealed from him. The X-ray test showed he had shadows on his lungs at that time.

Feng tried to get compensation from the mine owners but failed because he didn't have a contract. He says 11 of his co-workers have died from the disease. He hasn't worked since 2008, although he has been taking medicine.

"Even climbing stairs is hard for me. I have to stay at home and do nothing," Feng says.

"Medicines are very expensive, and I am a burden to my family."

In the early stage of the disease, therapeutic irrigation, or lavage, is effective but costs about 10,000 yuan ($1,579) a treatment.

Zhao Qingqiong, Feng's doctors, says the cost of pneumoconiosis treatment is far too high for migrant workers. And the longer the delay for treatment, the worse the disease will become.

When complications, such as pulmonary emphysema and tuberculosis, set in, treatment becomes even more difficult.

For advanced-stage patients, even a cold is life-threatening, Zhao says.

Paying for treatment is a big issue for those like Feng, who do not have free medical treatment - like employees of State-owned mines. And medical insurance usually does not cover the treatment of pneumoconiosis.

The only solution is to try and get compensation from their employers. By the time the diagnosis is made, however, the mine may have gone bankrupt or disappeared.

The Law on Occupational Illness Prevention and Control issued in 2001 required pneumoconiosis patients to present enough evidence to link their symptoms to their occupational activities and for their illness to be diagnosed as an occupational illness by a certified organization before claiming compensation from an employer.

"It was hard for us to prove that we got the disease from working in a mine in order to get compensation, even though that was the fact," Lu Quanjun says.

Lu is unable to work now, and the family relies entirely on the money his wife earns from running a barbershop, which brings in about 1,000 yuan a month.

"We cannot get compensation from the mine owners because the management has changed and we didn't sign a contract," Lu says.

"I hope the new law will help us get financial assistance from the government."

However, Zhao Qingqiong at Central Hospital of Tongchuan City Mining Bureau says assistance will depend on local governments and their financial conditions.

"Migrant workers usually come from less-developed areas, and these local governments may not have enough money or the will to help them out," Zhao says.

Today's Top News

Rescuers race against time for quake victims

Telecom workers restore links

Coal mine blast kills 18 in Jilin

Intl scholarship puts China on the map

More bird flu patients discharged

Gold loses sheen, but still a safe bet

US 'turns blind eye to human rights'

Telecom workers restore links

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|