Society

More questions than answers

Updated: 2011-09-04 07:54

By Zhang Xiaomin and Eric Jou (China Daily)

While there is trepidation about current leakage from the Penghai oil rigs, fishermen on both sides of Bohai Bay are convinced that pollution has already taken its toll. Zhang Xiaomin and Eric Jou look at grass-root concerns in Liaoning and Hebei.

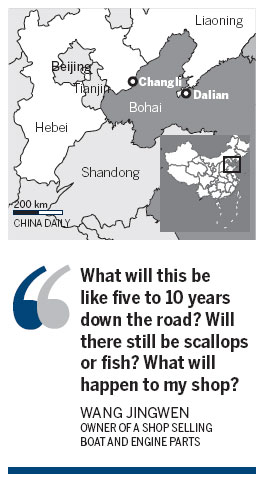

On the fishing wharf at Xinkai-kou at Changli county in Hebei province, Guo Shunyi, 40, gazes out at Bohai, where he has spent half his life eking out a living. The fishing boat captain says water quality is bad, and even if it seems to be thriving on the surface, life under the sea is fading.

Guo also farms scallops in the surrounding water, and he tells us the best way to gauge the water is from the effect on shellfish, especially more sedentary species like clams, mussels and cockles.

"You see it every other season. If the water quality is bad that year, the amount of shellfish harvested will be affected," says Guo. "It's particularly obvious when you seed scallops. The usual return is about 70 percent, but now, at least 30 to 50 percent will die before they mature."

The small wharf is home to a fleet that ranges from large boats that go far out to sea to smaller vessels like trawlers that harvest scallops and other shellfish. Xinkaikou is about 350 kilometers away from the Penglai 19-3 oil field currently leaking oil into an already fragile ecosystem. The spills have been going on since June 4.

The aftermath has not hit home fully, yet. Guo and other Xinkaikou locals are still not too concerned about the oil leak that started two months ago.

Guo says this season's scallops are coming along nicely, and there haven't been any sighting of oil.

Wang Jingwen, 57, has lived by the gulf all his life. He owns and operates a shipping parts shop that services local fishermen and shellfish farmers. In his eyes, the environmental damage caused by humans is obvious.

Wang worries that his days are numbered here. His shop is basically a small garage filled with boat parts and equipment. His weathered face is a familiar sight on the wharf, his skin dark and tanned from years of working on the docks, his hands calloused from working the boats. He has been here all his life.

"I'm worried. We can't see any oil now and I don't know if it will ever reach us, but I'm still concerned," he says. "What will this be like five to 10 years down the road? Will there still be scallops or fish? If there's nothing alive in Bohai anymore, what will happen to my shop?"

We had to leave him with his questions.

|

On the other side of the bay is Dalian in Liaoning province. Best known as a seaport, Dalian rests in a special spot bordered by Bohai and the Yellow Sea. Here, they are not worrying about the latest oil spill.

They are still too busy cleaning up after the last one.

Only a year ago on July 16, Dalian suffered when two oil pipelines exploded in the Yellow Sea. The area, known for its seafood farms, was devastated when at least 60,000 tons of oil seeped into the Yellow Sea. Scientists have said it may take years for the ecosystem to recover from the incident, and now there is a similar disaster just about 200 km away.

Shao Deshan, the head of the Hezuizi village council, recounts grim tales of death and destruction in the aftermath of the Yellow Sea oil spill. Hezuizi village, a small hamlet in the Jinzhou New Area, was only a few kilometers away from the spill and its livelihood was severely affected.

"Dead seaweed and jellyfish washed ashore, the seagulls were either washed up dead or were gone because there was nothing to eat," Shao remembers. "Villagers got sick after eating contaminated fish because they did not know better."

The area is famous for its abalone and sea cucumber farms, all on the ocean floor. These farms take time to nurture and Shao says the spill wiped out years of produce waiting for harvest. He estimates that last year's oil spill, commonly referred to as the "716 Incident", has wiped out at least five years' worth of seafood.

Shao Lin, an abalone farmer, took out a 15-year lease, and he says he's basically working on a negative balance now that his first harvest was ruined.

Yet, despite the fact, he is driving a brand new 2009 BMW X series SUV with a market value of about 1 million yuan ($157,000).

"The oil company was asking fishermen with boats to help gather the leaked oil," says Shao Lin, with a slightly bemused expression. They were paid about 300 yuan for every barrel recovered and Shao says he got about 1.63 million yuan for the oil he brought in.

"If the oil spill did not occur, I would have made more money," he says, estimating that his abalone harvest would have been worth about 7 million yuan.

When we asked him what he plans to do with his 15-year lease, Shao Lin smiles cynically and says he can only keep seeding the ocean floor in the hope that he can recuperate his losses.

Shao Deshan has led his village to petition in Beijing over the handling of the compensation given to fish farmers and fishermen in the Dalian area for the 716 incident.

The petitioners are upset over the amount given and also over who is footing the bill, currently the Dalian municipality government. Shao and his villagers feel that the compensation should come from the oil company and not from taxpayers.

But Tang Zailing, the head of Dalian's environmental volunteer museum, says there are problems with the Hezuizi petitions, as well as those from other fishing villages. He cites discrepancies in reported losses as well as insufficient knowledge of the cause of environment damage.

"Some fishermen report losses that are too high in trying to get a few extra yuan from the payout," says Tang. "But the real problem isn't that they are trying to tweak numbers, it's the fact that they don't know for sure what is killing their fish stock - be it years of environmental damage already inherent in the waters, or the 716 oil spill, or even the current Penglai 19-3 spill."

To Tang, Bohai is already pretty polluted, and he feels the 716 accident was dealt with rather well, and that it had limited impact on the environment.

"Seaweed and seagulls are coming back," he says cheerfully. But almost in the next moment, he turns solemn as he admits another problem.

Coagulants used in the cleaning up of the spills have caused the oil to clump and drop down into the sea floor as black pellets. They will take a long time to biodegrade and may pose a threat to the shellfish industry, especially to ocean floor farms.

For both the environmentalists and the fishermen, a solution can well become yet another lethal problem - and if we do not find a way to break that vicious cycle, Bohai will continue to die and become an empty sea devoid of life.

You may contact the reporters at

zhangxiaomin@chinadaily.com.cn and ericjou@chinadaily.com.cn.

E-paper

Unveiling hidden treasures

The Forbidden City, after the Great Wall, is the most recognized tourist site in China.

Short and sweet

Game for growth

Character reference

Specials

China at her fingertips

Veteran US-China relations expert says bilateral ties have withstood the test of time

The myth buster

An outsider's look at china's leaders is updated and expanded

China in vogue

How Country captured the fascination of the world's most powerful fashion player