Society

Peer pressure

Updated: 2011-08-01 08:14

By Erik Nilsson (China Daily)

Peer educators at Emei's Five-Hearts Service Center. They often visit the city's drug users' hangouts to tell them how methadone can transform their lives and educate them about HIV/AIDS prevention. Erik Nilsson / China Daily |

The Five-Hearts Service Center in Emei city, Sichuan province, is helping intravenous drug users climb out of the abyss of their lives, through an innovative program. Erik Nilsson reports.

Like most intravenous drug users (IDUs) in Sichuan province's Emei city, Tong Xiaolin had no idea what heroin was when she started using it in 1992.

The 15-year-old was earning a living as a hotel sex worker in Guangdong province when a colleague from Emei offered her a dose and told her it "feels good", she recalls.

"Sometimes, I would feel really depressed after a customer forced me do things I didn't want to," Tong says.

"Heroin numbed that hurt."

But she had little inkling her worst suffering was yet to come, she says.

"When I first felt withdrawal symptoms, I had no clue what was happening," she recalls. "I'd never felt pain like that!"

Tong asked friends about it.

"They told me heroin was addictive," she says. "That was the first time I'd heard this - too late."

The following decades brought divorce, robberies and five arrests. She spent more than three years in labor education, rehab and jail.

Tong's daughter, now 6, came into the world vomiting and twitching from withdrawals. The nurses refused to wash the newborn because Tong was an IDU, the mother says.

"My friend suggested I smoke some heroin and blow it in her face," Tong recalls.

"I refused. She had to fight for her own life. She did. She won."

Tong is also winning her life back through methadone and working as a peer educator for Emei's Five-Hearts Service Center, a peer-led organization started by the International HIV/AIDS Alliance's China office and funded by the Levi Strauss Foundation, which has provided $420,000 to the Alliance since 2005.

"Heroin users on methadone are fully functional," Emei Drug Maintenance Community Clinic director Zhang Yonghao explains. "They're just like anyone else."

Methadone is a synthetic narcotic that is used for pain relief and as a heroin substitute in the treatment of heroin addiction.

Subsidies reduce the cost of about 450 yuan ($70) a dose to 10 yuan ($1.55).

"Economic necessity drives most IDUs to the clinic," Zhang says.

The Alliance's Sichuan program officer Fang Xin explains: "They say heroin is like meat and methadone is like vegetables. After eating only vegetables for so many days, you want meat," Fang says.

"Heroin users need methadone like diabetics need insulin. But many locals don't understand this."

The Emei methadone clinic's 98-percent retention rate is the country's highest, the city's center for disease control and prevention (CDC) deputy director Wang Yi says.

Wang believes the success is largely because of Five-Hearts' 10 peer educators, who visit IDU hangouts - mostly bus and train stations, because they're trafficking points atop Yunnan province, close to infamous the Golden Triangle that overlaps the mountains of Myanmar, Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand.

The peer educators tell IDUs how methadone transformed their lives, educate them about HIV/AIDS prevention and point them to Emei's needle exchange program, which swaps about 1,400 used syringes - about 20 a user - for new ones a week.

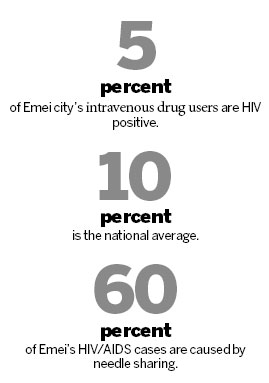

About 5 percent of Emei's IDUs are HIV positive, Wang says.

"Without these programs, it might be 10 percent - the national average," he says.

Needle sharing causes more than 60 percent of local HIV/AIDS cases. But there are no figures for overall infections in the city of 430,000, Wang says.

CDC surveys have found 99 percent of Emei's teens and 95 percent of its rural dwellers are aware of needle-sharing risks. But almost nobody knew in the 1980s and 90s, when heroin use and HIV/AIDS exploded in the city.

Zheng Bin was among the few who knew about the HIV/AIDS risk and never shared needles - except for once, he says. The 39-year-old believes that was when he contracted HIV.

"There are medicines for heroin addiction and AIDS," he says. "But there's no medicine for regret."

He had hired a motorcycle to take him to the countryside to buy heroin when police scattered the purchasers.

Zheng and three others hid in an abandoned house. His ride had fled, and it would take hours to get clean needles. So, they washed a syringe in rainwater and all shot up.

"I knew about HIV, but I thought it was only in remote areas like the border of Yunnan," he says. "I had no idea it was already in Emei."

Zheng was tested after he displayed HIV symptoms during a labor education stint in 2005 but not informed of the results. After his release, he tested negative at Emei's CDC in 2006 and in 2007.

But in 2008, the labor education authorities phoned the CDC, who called Zheng, to inform him his 2005 test was positive.

"The discrimination against IDU and HIV is different," Zheng says.

"People are annoyed by IDU friends, because they always ask for money. But they won't be friends with people with HIV, because they fear the disease."

Only the other peer educators and his mother know, he says.

"My best friend is fine with me being a heroin addict but wouldn't be with me having HIV. I can't call him anymore."

Zheng's diagnosis was the trough of his downward spiral, he says.

He started using heroin in 1991, at the suggestion of a gangster friend who was hiding in his house after a mafia turf war in neighboring Leshan city.

Zheng had tried it once and hadn't become addicted, so he started using it to help his insomnia.

Over the next five years, he spent his savings of 500,000 yuan on heroin and failed addiction treatments.

Because there was no rehab in Emei, he went to a nearby county's railroad hospital.

"The doctor gave me some medicine, but the withdrawals were so painful," Zheng recalls. "I tried to jump out of the sixth-story window, but my friend blocked me."

In 1995 and '96, he checked into a military hospital's psychiatric ward for 10-day rehab sessions that cost 2,000 yuan each.

"The moment I got out, I did heroin," he says.

"I was out of money and started scamming my parents. They quickly figured out why."

He started injecting in 1997 to save cash. Heroin costs 300 yuan a day if taken orally but goes twice as far if shot up.

"I started doing it all the time - after I woke up, before and after breakfast, before and after showering, before and after lunch, before and after dinner, before bed. I shot up like chain-smokers smokes cigs."

The police fined him 11 times between 1995 and 2003. Starting methadone and the opening of Five-Hearts ended Zheng's "hopelessness", he says.

"Joining this group helps so much," he says. "Here, we're all equal. We're friends and joke around."

Discrimination dominates the lives of Emei's IDUs, Fang says.

"It's a very small city. Everybody knows everybody," he says. "IDUs and their family members are marginalized."

This essentially makes users unemployable. But they can't leave Emei, because they rely on their families and often lack work skills, the Alliance's China director Grace Lo says.

"They want to have the right to employment," Lo says.

"A job means not only money but, most importantly, self esteem and less time to get emotional and think about having an injection."

Five-Hearts' group leader Ou Hongquan says his experience as a peer educator has helped.

"It has taught me how to earn respect from myself and others," Ou says. "Now I know I'm not useless. I'm useful. Our dream is that through our hard work, our group can become one of the biggest consultative centers for IUDs and policy."

Zheng says about 80 percent of the IDUs he approaches on the street come to the methadone clinic. He estimates he has directly helped 400 users.

Tong hasn't been able to find work outside of Five-Hearts. The group provides 300 yuan a month, which she spends on cigarettes and fruit.

"One manager promised to hire me, but an employee knew my background, so the manager never called back," Tong says.

"I was also hired as a department store saleswoman. But some employees knew my history, and I was fired halfway through my first shift. No matter who you are, people will always see you as who you were."

Families face discrimination, too.

"Kids bully my girl and call her 'junkie's daughter' and 'criminal'," Tong says.

"She's innocent. She doesn't deserve this. I feel so sorry for her. I want to quit heroin forever for her."

Parents suffer isolation, too, and the Five-Hearts Center runs support groups and education campaigns for them, explains Li Sufang, whose 43-year-old son has used heroin for 10 years.

"My son's crimes brought shame to our family," the 67-year-old says.

"Our relatives and friends despise him, even though he's on methadone and normal again. Other families won't talk to us."

The parents' group stages educational events for 20 new users' families a month.

"They know heroin is harmful, but they don't know how harmful," Shen Liuqing, whose 34-year-old son is an addict, says. "They know nothing about HIV."

Parents also share their experiences.

"My son came home bloody from beatings," Li says. "One time, a huge patch of his scalp was torn off and his face was slick with blood. I felt so sad to see my boy mangled."

The IDUs often hurt themselves, too.

"My son was sentenced to labor education and decided he'd rather die than endure withdrawals," Li says. "So he hacked open the veins in his inner thighs."

Shen recalls her son often threatened suicide if they refused to give him money.

"He'd hold a knife to his wrists. He slashed them three times," the 62-year-old says.

"We gave him medicines, but they made him go crazy. He leapt out the window and broke his leg."

Shen's family strapped her son to his bed and tranquilized him, she says.

"The tranquilizers were cheap - just 2 yuan a dose - but useless. As soon as we'd free him, he'd shoot up," Shen says.

"The longest we tied him to the bed for was four days. But he wouldn't eat. All he could think about was heroin. We had to set him free or he'd starve."

But methadone changed everything, the parents say.

Five-Hearts' methadone message is getting through to Li Jing, who says he hopes to start next month.

"I've done heroin for 15 years. I'm tired of it," the 42-year-old says.

"My life is two things - heroin and sleep. It's insane. I have no girlfriend, no wife, no child, no house. I have nothing. I'm miserable. But it's hard to quit."

Li holds up his swollen, purple hands and explains, "I can't inject anywhere. My veins are destroyed. I've had to take it orally for 50 days."

He knew heroin was a drug when he started, he says.

"But I didn't know it was serious. Everybody was doing it," Li recalls.

"I didn't know you could get HIV from needles until Five-Hearts opened. Fortunately, I've never shared and don't have HIV."

Zheng, the IDU who is HIV positive, says he hopes to live to see a cure.

"Otherwise, I have no dreams for my life," he says. "My only hope is for society - that it will contain fewer people like me."

He and his peers agree that the project in Emei makes this hope viable.

E-paper

Double vision

Prosperous Hangzhou banks on creative energies to bridge traditional and modern sectors

Minding matters

A touch of glass

No longer going by the book

Specials

Carrier set for maiden voyage

China is refitting an obsolete aircraft carrier bought from Ukraine for research and training purposes.

Pulling heart strings

The 5,000-year-old guqin holds a special place for both european and Chinese music lovers

Fit to a tea

Sixth-generation member of tea family brews up new ideas to modernize a time-honored business