Society

Circle of life

Updated: 2011-07-14 07:58

By Zhao Hanmo (China Daily)

|

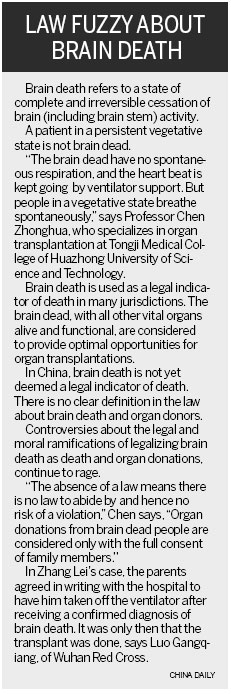

Top: Zhang Tianrui and his wife Hu Jiuhong visit the Body Donors Monument at Shimenfeng cemetery in Wuhan, Hubei province. Above: Zhang Lei worked as an intern at a TCM hospital before his life ended tragically in a traffic accident. Above right: Zhang Tianrui at home. Photos Provided to China Daily |

A poor couple's son was their only hope for a better life, swallow their tears over his untimely death and give five others a new lease of life. Zhao Hanmo reports.

Standing before the Body Donors Monument at Shimenfeng cemetery in Wuhan, Hubei province, Zhang Tianrui's eyes fill with sorrow as he bends down to caress the 385th name carved on the gray stone. It reads Zhang Lei, the only child of the 49-year-old, whose painful decision has given five critically ill people a fresh lease on life. Two of them, with inflamed corneas can now see, two with kidney problems have been taken off dialysis machines, and a woman with liver cirrhosis can finally eat normally.

These are 22-year-old Zhang Lei's gifts to the world after his young life ended in a horrific accident.

Although a wrenching decision, Zhang Tianrui and his 48-year-old wife Hu Jiuhong say, "This was the only way to keep our son alive".

Both Zhang and Hu are laid-off workers, living in a 30-square-meter house, that doubles as their shop, in a county of Jingmen, 150 km from Wuhan.

Zhang supports the family by delivering gas cylinders. For each 30 kg cylinder he delivers, he earns 5 yuan (77 US cents). His wife, who is disabled from poliomyelitis, manages household chores.

The room, filled with the thick smell of gas, can barely accommodate three stools, two beds, an old fridge, and a secondhand TV set.

Their son was the couple's only hope for a better life.

Zhang Lei had just completed his nursing course and was working as an intern at a TCM (traditional Chinese medicine) hospital. Once he paid off the 4,800 yuan in tuition fee he owed to the college, he would have received his graduation certificate that would have allowed him to join the hospital as a full-time nurse.

"He was not smart, but he was nice, and obedient to us," the father says.

Hu recalls the rosy pictures her son painted of the family's future after his graduation. "I will find a job, whatever it is, then you and father will have easier days," he used to tell Hu.

Zhang's girlfriend (she did not want to be named), 20, says she was happy with him.

"He had an attractive smile, and spoke so gently," she says, "He would listen patiently to all my plans of our future home and promised me he would make it happen and take care of me and his parents."

But fate had other plans. Zhang Lei was hit by a tractor on the morning of May 31 at a crossroad, 1,000 meters from his home. He was on his way to the hospital to pick up his internship certificate.

There were no major injuries to his body, but he had taken a serious hit to the brain.

Following emergency operations, he fell into a coma and was put on a breathing machine.

The desperate parents tried everything to revive him.

Hu recalls how she and her husband held their son's hand tightly, saying over and over again: "If you're really the good boy you have been, just wake up to see us."

On June 4, the doctors announced Zhang Lei was brain dead and painstakingly explained to the devastated parents what this meant.

It was during these explanations that Hu heard about a practice that she decided to follow, shocking everyone in the small county.

"When the doctor told me about organ donations from brain dead patients, I asked him if my son could undergo a brain transplant to save his life," she says.

"Not possible," the doctor replied.

Then she began to think of those critically ill people lying in hospitals, waiting for life-saving organs.

She saw donating her son's organs as a way to not just to help these people but also keep him alive.

The county had, till then, not seen even one instance of organ donation. Social customs dictate it is taboo not to keep the remains of a dead person intact.

None of Hu's relatives agreed with her decision, not even her husband.

Zhang says there were even whispers that they were doing it for money.

After spending a sleepless night, Zhang finally agreed: "Our son would turn to ashes after cremation. But donating his organs would give his life meaning."

Three doctors arrived with Luo Gangqiang, a Wuhan Red Cross member in charge of organ donations, at 11 am on June 5.

The team determined Zhang Lei could be a healthy donor of several organs and skin.

"Will my son feel hurt from offering so many things?" Zhang Tianrui asked.

"The operation is the same, whether for one organ or several. More organs mean more lives saved," Luo told the couple.

Zhang and Hu finally signed the agreement.

That afternoon before the operation, Zhang, a tough man with a loud voice, broke down by his son's hospital bed.

"I feel like you will live on, at least in parts," he murmured to his son.

Hu wasn't able to speak. She hugged her son one last time, her face on his.

The three doctors and nurse bowed to Zhang Lei after the operation, and left with the young man's organs to hospitals in Wuhan.

Early in the morning on June 6, a 25-year-old uremia patient survived the kidney transplant. She had been suffering for 11 years and her family had all but given up hope of saving her.

Her mother realized the source of her daughter's life-saving organ when she chanced upon news of Zhang Lei.

"As a mother, I know what the family must be going through," she says with tears.

"How great these parents are to have saved so many lives."

The story first appeared in China Youth Daily.

E-paper

Ringing success

Domestic firms make hay as shopping spree by middle class consumers keeps cash registers ringing in Nanjing

Mixed Results

Crowning achievement

Living happily ever after

Specials

Ciao, Yao

Yao Ming announced his retirement from basketball, staging an emotional end to a glorious career.

Going the distance

British fitness coach comes to terms with tragedy through life changes

Turning up the heat

Traditional Chinese medicine using moxa, or mugwort herb, is once again becoming fashionable