Society

Wanted in India, one good hangman

Updated: 2011-06-26 07:37

By Jim Yardley and Hari Kumar (New York Times)

MEERUT, India - India has 1.2 billion people, among them bankers, gurus, rag pickers, billionaires and software engineers. What it needs is a hangman.

Usually, India would not need one, given the rarity of executions. The last was in 2004. But in May, India's president unexpectedly rejected a last-chance mercy petition from a convicted murderer in the Himalayan state of Assam. Prison officials, compelled to act, issued a call for a hangman.

No one answered. Not initially.

The nation's handful of known hangmen had either died, retired or disappeared. The situation was unsurprising, given the ambivalence within the Indian criminal justice system about executions. In recent decades, capital punishment in India has been limited to "the rarest of rare cases."

Prison officials reluctantly began a search. Assam's last execution was in 1990 and the memory still resonated. "I was very conflicted," said Banikanta Baruah, a retired jailer who supervised the execution. "On one hand, I needed to perform my duty as a jailer, yet on the other, I sympathized with the person being hanged."

The search eventually led to Meerut, in the state of Uttar Pradesh, the home of a family known for executions. Kalu Kumar, himself the nephew of a hangman, had achieved national fame in 1989 by hanging one of the two assassins of Indira Gandhi, the former prime minister. He died several years ago but passed the trade to his son, Mammu Singh, who claimed to have performed 11 hangings.

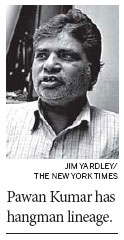

Mr. Singh died May 19. Officials called the state's only other hangman, in the city of Lucknow, but he had broken his arm. Then Mammu Singh's eldest son, Pawan Kumar, decided to enter the family business. Ten days after his father's death, Mr. Kumar applied for certification as a hangman.

"I just want to continue the family legacy," Mr. Kumar said.

Mr. Kumar, who works as a hawker, selling clothes from the back of his bicycle, said he welcomed the possibility of a $75 monthly retainer.

And the workload could increase. India, which has put to death at least 50 convicts since becoming an independent nation in 1947, had 345 people on death row by the end of 2008.

Officials told Mr. Kumar that they would expedite his application. However, India is known for its bureaucratic delays. There are regulations over the length of the rope, the construction of the gallows and more.

Meanwhile, the defense lawyer for the condemned man in Assam filed an emergency motion with the courts. Indian defense lawyers long ago introduced the argument that forcing someone accused or even convicted of a capital offense to wait for years before an execution amounted to cruel and unusual punishment.

The condemned man, Mahendra Nath Das, was convicted in 1997. It is unclear when the courts will rule on the latest petition.

Mr. Kumar was invited for an interview with prison officials.

But, for now, India may not need him.

The New York Times

E-paper

Franchise heat

Foreign companies see huge opportunities for business

Stitched up for success

The king's speech

Tough sail

Specials

Premier Wen's European Visit

Premier Wen visits Hungary, Britain and Germany June 24-28.

My China story

Foreign readers are invited to share your China stories.

Singing up a revolution

Welshman makes a good living with songs that recall the fervor of China's New Beginning.