Society

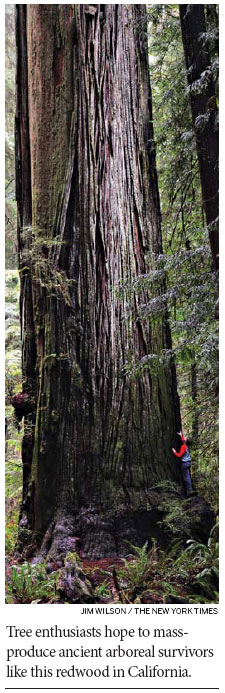

Cloning red giants to rescue the Earth

Updated: 2011-04-24 08:05

By Jesse Mckinley (New York Times)

|

FORT DICK, California - Shooting skyward like a jagged knife, the giant stump in a cul-de-sac in this Northern California town is by all appearances dead. But Michael Taylor, a professional big-tree hunter, knows otherwise.

"This snag is partially alive," he explained, pointing to dozens of green sprouts on the trunk.

It is just those sprouts that lie at the heart of a plan hatched by a group of tree enthusiasts to clone - and then mass-produce - a collection of colossal redwoods, some of which date to before the birth of Jesus and can soar nearly 40 stories, the tallest living things on earth.

"We want to get the biggest, best genetic representations of the species," said David Milarch, the co-founder of the Archangel Ancient Tree Archive. "And make millions and millions and millions of them."

Mr. Milarch says that his mission is simple, if grandiose: to reforest the land with a variety of the most interesting tree species from around the world, and by extension, halt and reverse climate change.

"Everyone knows the problem, everyone knows the bad news," said Mr. Milarch, a ruddy, jovial chain-smoker and a sixth-generation arborist. "This is the solution."

That is debatable. But Mr. Milarch's approach is unique. Cloning plants is nowhere near as difficult or sophisticated as cloning animals or other life forms. But it can be delicate work. Bill Werner and other project propagators use various methods to clone two types of redwoods, coastal and giant sequoia. Those include so-called micropropagation, which basically uses tiny samples of plants, fed with heavy doses of synthetic growth hormones and nursed in a laboratory environment, to create genetically identical plants.

Mr. Werner used small cuttings of sprouts and other plant material, including some cuttings from the upper reaches of giant sequoias. He coaxed them into growing, and eventually, into growing roots. They were then transplanted to enriched soil, where they are now several centimeters high.

Mr. Milarch believes that this may be the first time that such ancient trees have been cloned in such a fashion. .

"What Bill has done is somewhere between what we thought was difficult and impossible," said William J. Libby, an emeritus professor of forestry and genetics at the University of California, Berkeley, and a consultant to the Archangel project. "And he moved it from impossible to difficult."

Mr. Milarch's efforts to capture the DNA of famous trees, which he has been at for nearly two decades, have raised concerns with tree experts, as has his plan to sell the clones, something he says is necessary to finance his project. Connie Millar, a research scientist with the United States Forest Service, said it also did not necessarily track that the biggest, oldest trees had the best genes. "The longest-lived trees could just be sitting on top of a water table, or sitting on especially rich soil," said Ms. Millar.

Some scientists were curious about whether the replicas would have the same genetic defenses against disease or environmental changes that evolution had developed in today's forests.

And Scott Steen, the chief executive of American Forests, questioned the practicality of ancient redwoods. "They're not the kind of tree you can plant in your backyard unless you have a really big backyard," Mr. Steen said. "And you can't really line a city street with them."

Mr. Milarch says the group had selected trees for "longevity, survivability and their natural abilities to benefit and repair the environment."

He added, "If we don't archive these ancient survivors now, they won't be available for scientific study in the future."

Redwoods were heavily logged in the 20th century. Only about 5 percent of the native old-growth redwoods remains.

And the stumps that remain are often viewed as nuisances. For Mr. Taylor, they are bounty. Mr. Milarch pays him for each of the stumps he finds.

At Fort Dick, Mr. Taylor circled the stump nicknamed the Big Snap, about 7.5 meters in diameter. "This was a huge tree," he said. "And maybe it will be again."

The New York Times

E-paper

Blowing in the wind

High-Flyers from around the world recently traveled to home of the kite for a very special event.

Image maker

Changing fortunes

Two motherlands

Specials

Urban breathing space

City park at heart of Changchun positions itself as top tourism attraction

On a roll

Auto hub Changchun also sets its sight on taking lead in railway sector

The stage is set

The Edinburgh International Festival will have a Chinese flavor this year.