Bite-sized delights

Updated: 2015-08-04 08:00

By Xu Junqian(China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

A Shanghai chef finds ways to make dim sum a treat for all the senses, Xu Junqian reports.

After almost 20 years in the kitchen, dim-sum chef Eric Zeng believes the appearance of these Chinese bite-size snacks is very important, and he strives to present them in a way that is almost "superficial".

"Dim sums have never been a staple on the table," says Zeng. "To help them steal the thunder from the plump roasted goose or shiny golden rice, my first trick is to dress them up."

|

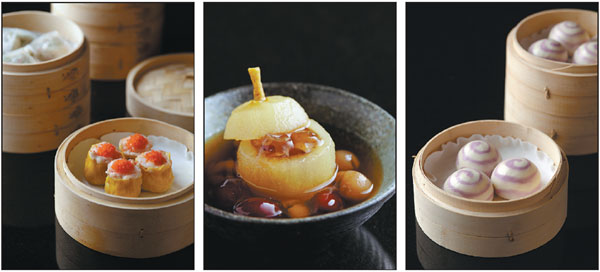

From left to right: Shiu mai with crab roe, double-boiled pear with dried longan, sesame peanut bun. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

Dim-sum chef Eric Zeng believes sticking to the tradition of making everything from scratch is what makes his dumplings and buns stand out. |

At Vue Dining, the Cantonese restaurant where he has just taken over the reins, for example, the tea-smoked scallop dumpling teases all of your senses. As tea leaves and buds of lavender, chrysanthemum and jasmine take a sauna on the hot stones under the bamboo basket - filled with three delicate, transparent and triangular dumplings - your nose is treated to a feast of fragrances from the sweating tea leaves.

The treat for the tongue that followed is less fancy, more elemental: The scallop filling is juicy, muscular, and flavored with nothing but salt.

"It's the flavor of nature," says Zeng, both about the dumplings and the floral tea fragrances. You are unlikely to miss the "civilizing" touches of MSG or even soy sauce.

Zeng has developed upward of 300 types of dim sum.

"It actually becomes fun to play around with the sheet of dough skin with different tricks. It's no longer a job," the chef says. But the 40-year-old believes sticking to the tradition of making everything from scratch is what makes his dumplings and buns stand out in Shanghai.

While The New York Times and Wall Street Journal have both translated dim sum as "touch of heart", Zeng says what they touch first is the diners' eyes. Only when the eye is caught will the heart and stomach be tempted.

"Dim sums are generally cheap and insignificant," says Zeng, but he scorns chefs who top or stuff the snacks with pricy ingredients - like caviar or foie gras - just for the sake of charging a premium price.

A native of Guangdong province, where this branch of Cantonese cuisine is believed to have originated, Zeng similarly shrugs off yan bao chi, the Chinese shorthand for bird's nest, abalone and shark's fin, the three most popular expensive ingredients used in Cantonese cuisine. The term is now a synonym of any food that is pricy.

Zeng started his trajectory in the kitchen early in the 1990s, when China's reform and opening-up policy was just taking effect. Dining out then simply meant feasting on the most expensive species available among the nouveaux rich, and Zeng jokes that his appetite for yan bao chi had already been sated during his apprentice years simply by looking at and cleaning them.

On the other hand, his three-year experience of working with Hong Kong master chef Dai Long pushed Zeng to be as creative as possible with the palm-sized paper-thin sheet of dough skin.

He says Dai always told him: "You are just making dim sums, not atomic bombs. Try whatever comes to your mind." When nothing came to his mind, Zeng got yelled at by China's version of British celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay.

Dai is a legendary chef in China, believed to be the prototype of the country's first and by far most famous comedy movie God of Cookery by Stephen Chow. His theory of Chinese fried rice is widely quoted and used as a textbook guideline. That is: Instead of using freshly steamed rice, it's better to use overnight rice so that every particle of the rice is dry enough and can fully absorb the egg yolk and other flavors when fried the next day.

Zeng says he never minded "being yelled at" by Dai: Having the master's attention, he says, was like winning the lottery every day.

If you are interested in the flavor of a thousand-year-old tradition, try the sesame and peanut bun. Instead of using ordinary lard to mix the baked walnuts, peanuts, sesame and other fillings he uses for various buns, Zeng has gone to the old-fashioned pig caul, a membrane from the intestines that is much fatter but less greasy than lard.

"The flavor of the caul is subtle, if any. But it offers all the nuts a special moisture that can makes them flowing and fragrant," Zeng explains. It is calculated that every pig could produce a maximum of 1 kilogram of caul, which can moisten the fillings of 10 buns.

"There are so many things from nature and our tradition for me to wrap up in the sheet of dough skin," the chef says.

Contact the writer at xujunqian@chinadaily.com.cn

Today's Top News

17 armed forces take part in Russia military contest

China joins hands with UK for

arts exchange

CPC leaders' annual meet to set economic agenda

Sinopec denies report on recalling overseas staff

China to use satellites, drones, sensors to monitor pollution

View the 'Belt and Road' initiative as a great 'Social Project': Sinologist

Turkey launches airstrikes on PKK targets

Last 'Dambuster' pilot in WWII dies at 96

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|