Two-way road

Antiques and artifacts are witnesses to the pivotal role in history of the ancient Silk Road

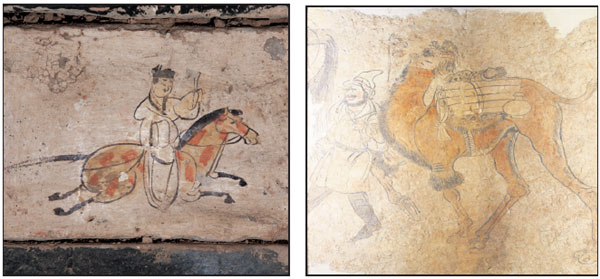

A man wearing a long, black-rimmed robe, with his hair wrapped in black cloth, charges forward on a stallion. While his right hand is placed on the halter, constantly pressing his mount, he raises his left hand, in which he holds a rolled-up document at the end of his broad sleeve.

The document, likely to have been written on bamboo slips, must have contained urgent messages, for the horse is galloping at top speed, its four feet completely off the ground and its bushy tail whipped horizontally backward by the strong wind.

|

A visitor at a Silk Road exhibition held in Chengdu Museum in 2017. Xue Yubin / Xinhua |

|

Left: A brick painting of a Silk Road courier charging on a horse, unearthed in Gansu. Right: A Sogdian merchant with his camel carrying rolls of silk, appearing on a Tang Dynasty mural painting unearthed in Luoyang, Henan. |

But the rider never arrived at his destination, and never will. Vividly captured in succinct lines on a piece of brick from around 1,800 years ago, the image is believed to have belonged to a courier from ancient China. The place where it was discovered, inside a tomb unearthed in the Jiayu Pass in Northwest China's Gansu province, suggests that the courier was no common messenger, but one shuttling on the famous Silk Road, on which the pass is strategically located.

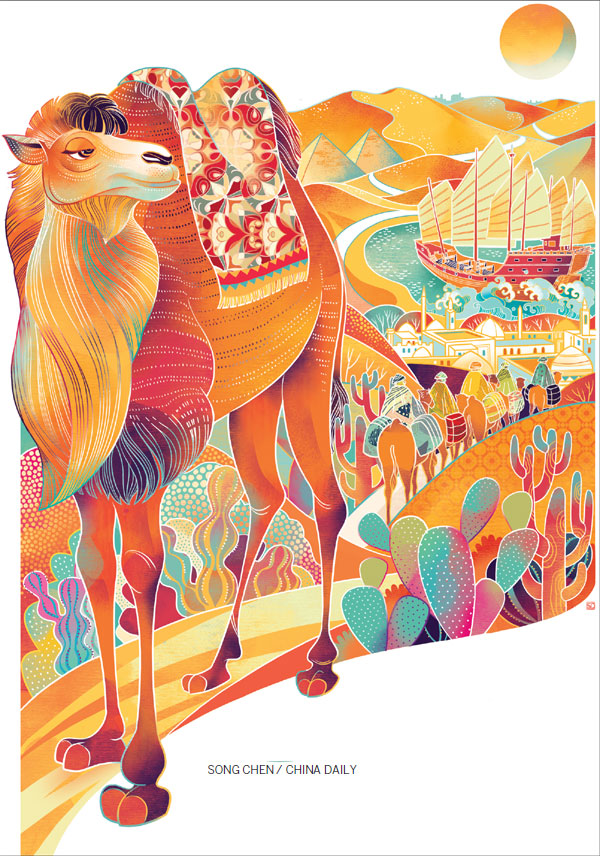

If anything, the light, unhesitant brush strokes, and the sense of spontaneity they convey, belie the hardship of a journey on a road that traversed Eurasia, from the heart of ancient China to the shores of the Mediterranean and Rome. On the way, it cut through forbidding deserts and scattered grasslands, skirting inhospitable mountains and deep depressions, before completing the entire 8,000 kilometers and stringing together a great variety of local cultures that came to form the diversity and dynamism of the Silk Road.

Today the desert wind that the ancient postman battled still howls, but the parade of people who once trekked and traded along the road has long since disappeared, with the vestiges of the cities, fortifications and temples of worship they helped build serving as solitary footnotes to what should be a hefty and heavily annotated chapter in the history of human exchange.

But not all was lost, says Ge Chengyong, a historian who was behind an exhibition held in Hong Kong recently titled Miles Upon Miles: World Heritage Along the Silk Road. More than 200 precious antiques were displayed in the exhibition, which ended in early March, and it told an immensely complex and infinitely fascinating story of human endeavor and engagement.

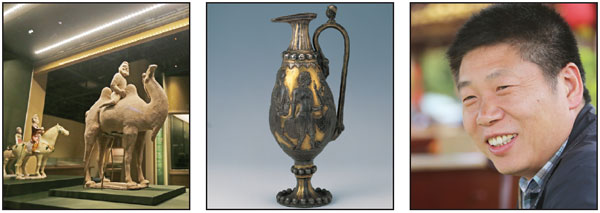

An example was a gilt silver, high-stem vase from a tomb site in Northwest China's Ningxia Hui autonomous region, through which the ancient Silk Road went. With three pairs of embossed characters, both male and female, wrapped around its body, the vase evokes scenes from the much-venerated ancient Greek epic Iliad (the vanity-fueled dispute for the golden apple among three goddesses, the seduction of Helen by Prince Paris of Troy and the return of Helen to her husband, King Menelaus of Sparta.)

The neck and bottom of the vase are rimmed by continuous beads, a typical decorative pattern from the Sasanian Empire (224-651), which was set up by the Persians in what is now Iran.

"Here we have from the burial ground of a Chinese general a beautifully crafted work of art mixing Hellenistic and Persian influences," Ge said.

Judging by the evidence, the scale of this cultural convergence lies far beyond the imagination of Emperor Wudi of China's Han Dynasty, who ruled between 141 BC and 87 BC. In 139 BC, Wudi sent a convoy on a westward journey that would eventually lead to the opening of the Silk Road.

The original goal of the powerful emperor was to obtain an alliance with the Kingdom of Dayuezhi, located in what is now Central Asia, against the marauding Xiongnu troops. A large confederation of Eurasian nomads that existed between around 300 BC and AD 450, these ferocious horsemen proved themselves to be the ultimate scourge for Wudi and for those who preceded and followed him. The convoy was led by Zhang Qian, the man known in China today as the "tunnel digger of Xiyu" (Xiyu means the western regions.).

The tunnel had to be dug centimeter by centimeter. In the same year of Zhang's departure, he was captured by Xiongnu soldiers. He was kept in confinement for 10 years before he managed to escape and continue on his westward journey.

He finally arrived in Dayuezhi. Although his request for an alliance was politely turned down and he was later recaptured by Xiongnu during his return trip, he again managed to escape, eventually returning to his homeland in 126 BC, with plenty to tell about an eventful journey.

Between 119 BC and 115 BC, Zhang Qian embarked on a second Xiyu-bound mission, under the auspices of Emperor Wudi, who was equally determined to fight the Xiongnu but now knew enough to hope for more. Zhang's 300-person convoy set out with not only hordes of sheep and cows, but also rolls of silk and bags full of gold coins. The wealth was intended to impress and to win over hearts and minds, and it succeeded.

Nearly 1,000 years after Zhang's death, silk and gold coins were still being carried and traded by those who traveled to and from the "tunnel", including the Sogdians, Parthians, Scythians, Babylonians, Indians and Zhang's fellow ancient Chinese.

Yet the coins, and even the silk fabrics, were no longer simply of Chinese origin. "Featuring either a Persian king or a Grecian goddess, the great variety of coins unearthed along this route have held up numerous little mirrors to the trade that once blossomed and beckoned people from far and wide," says Li Yongping, a senior researcher with the Gansu Provincial Museum.

"Archaeological excavations in Palmyra, an ancient city in present day Syria, have yielded silk fabrics that were decorated with the signature local grape patterns but were woven using Chinese methods. The possibility is that they were custom-made by Chinese weavers for customers they probably never got a chance to see," he says. "The famous Persian brocade, for example, had seamlessly woven Persian-Arab motifs into raw Chinese silk bought from Sogdian merchants who, thanks to their monopoly on trade on the Silk Road between the 4th and 8th centuries, were enviously dubbed the Jews of the ancient world."

Many of these men, says Zhang Deshui, vice-director of the Henan Provincial Museum, later stayed without ever returning to wherever they had come from. Today their tombs are found in large numbers in Luoyang, a city in western Henan province associated with golden eras of both China's Han (206 BC-AD 220) and Tang (618-907) dynasties.

"It is these common people, the anonymous trekkers who manned the caravan heading for the unknown, who have filled the Silk Road story with all its touching details and remarkable aspects. Their distinct images - in conical cap and slim, open-collared Central-Asian style outfit - also appeared inside the tombs of many local Chinese, in the form of both murals and pottery figurines."

Another item, apart from the renowned Chinese silk, that had become so coveted that it served as a hard currency on the Silk Road was spice. A couple of dozen types of spices - mostly used as fragrances for the wearers and their ambience - were frequently traded along the route, Ge says.

"The spice traveled in the opposite direction of the silk, from the Indian subcontinent to major Chinese cities. The Silk Road entered its heyday during the Tang Dynasty, an era of immense social wealth.

"High-society ladies routinely put imported fragrance powder inside their delicate shoes. But of course more went on their carefully painted faces. The glass bottles for the fragrance, coming all the way from Rome and exuding their alluring greenish-blue, were treasures in their own right. After use, the bottles were often donated by their owners to Buddhist temples, in whose underground storage some have been found in modern times," Ge says.

Another famous import to China is grape wine, from the traditional grape-planting regions of the Mediterranean. With the wine came the Grecian wine god Dionysus, whose image adorns the rucksack on the back of a pottery camel unearthed in Chang'an (now Xi'an), the Tang Dynasty capital.

Rong Xinjiang, a professor of history at Peking University who is one of China's leading experts on the ancient Silk Road, says he believes the adoption of the spice and grape wine cultures are just two signs of the open attitude of Chinese society at a time when it was brimming with confidence.

"The Silk Road is not merely a conduit for commerce, and what was being transported along it should never be simply viewed as goods. Culturally and artistically, it enabled a cross-pollination whose seeds were blown far and wide along the extended route.

"For the Chinese, the road is an eyeopener: The existence of an outside world was made known to them, in an intriguing and sometimes intimate way. Ever since Zhang Qian's adventure, the official history of every Chinese empire features a section headed 'the Chapter of Xiyu'."

To ensure that the road was safe and passage unhindered, successive Chinese emperors installed along it a defense, control and postal system, of which the painted courier image mentioned earlier offers a salient example.

Rong says: "Documents, either in wooden slips or pieces of yellow paper, have been found showing the registration of guests or provision of horse fodder at government-kept relay stations within the Chinese border, mostly in what is now Gansu province and the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. These guest stations were usually located near desert oases or water sources and were often paired with military beacon towers. The Great Wall, ancient China's ultimate defense line against the 'barbarians', was also extended to offer protection."

However, at least one thing has been constant through the history of the Silk Road: change. People - merchants, mercenaries or even marauders - were jostling and squabbling as they were moving. Regimes, from mighty cross-continental empires to agricultural statelets and pastoral tribes, rose and fell. The result is diverse languages, shifting identities, transient policies and changing beliefs, complicated by intrusions and conquests that equally disrupted and facilitated exchanges.

The Silk Road went into relative decline after the Tang Dynasty, although the flow of exchanges on the road never dried up, even in times of war.

Then came September 2013, when, during a state visit to Kazakhstan, President Xi Jinping announced his determination to revive the Silk Road, to extend it and to imbue it with a whole new meaning, against the backdrop of greater global connectivity.

More than 80 countries and organizations have signed on to the initiative, dubbed the Belt and Road Initiative (Belt refers to the Silk Road Economic Belt, while Road refers to the 21st century Maritime Silk Road, several sea routes developed simultaneously in history with the terrestrial one). It has also resulted in China forging a series of bilateral partnerships with the signing countries, particularly related to trade and infrastructure.

In May last year, nearly 30 heads of state and government as well as 1,200 delegates from countries and regions across the world descended on Beijing for the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation. The value of trade between China and Belt and Road countries reached 7.4 trillion yuan ($1.1 trillion; 989 billion euros; £870 billion) last year, rising by 17.8 percent year-on-year, the Ministry of Commerce says.

In his Government Work Report delivered on March 5, Premier Li Keqiang pledged the country's continued support for the grand plan. China will continue building major international corridors and deepen cooperation on streamlining customs clearance in markets related to the Belt and Road, he said.

In a speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, early last year, President Xi made a powerful call to all participants.

"We should unite and rise to the challenge. History is created by the brave."

Zhang Qian, who first opened the route at the risk of his life, knew all about it. In 166, nearly three centuries after the death of the explorer in 114 BC, the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius sent the empire's first official envoy to China.

One of Ge's favorite pieces shown in the exhibition in Hong Kong was a polychrome piece of pottery camel unearthed in a 1,500-year-old tomb site in Shaanxi, whose provincial capital was Xi'an.

A camel with a pair of sacks straddled over its back is in the midst of rising from a kneeling position. The load must be heavy and the animal must have struggled a little, something indicated by its gaping mouth, flared nostrils and front-gazing eyes.

"On the Silk Road, no rest is permanent, and the only way to complete a journey is to journey on," Ge says.

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

|

A Silk Road exhibition held in Xi'an in 2017. Li Yibo / Xinhua |

|

The site of an ancient Silk Road relay station in Xinjiang. Huang Huo / For China Daily |

|

From left: Pottery figurines of a Sogdian caravan on the Silk Road, on display in Hong Kong; a gilt silver vase unearthed from the Ningxia Hui autonomous region evokes the ancient Greek epic Iliad; Zhang Deshui, vice-director of the Henan Provincial Museum. Photos by Roy Liu / For China Daily and Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 06/22/2018 page1)