In the steps of enigmatic foreign dancers

The rapid growth of the Silk Road helped bring to China a group of people whose roots are the subject of debate

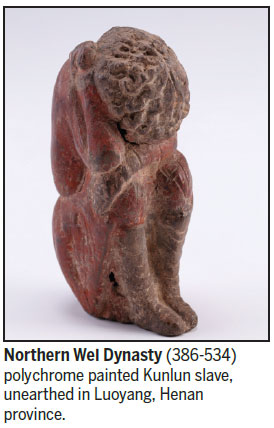

The young man - or perhaps he is an old adolescent - is visibly tired: sitting on a stool with his head buried in his lap and his forehead resting on one arm, he confronts the viewer with a full crop of exuberant curls. Invisible to us are his weary eyes.

But the story of the person portrayed by the pottery figurine, which can be fully told only by drawing on the imagination, still intrigues, even after 1,500 years.

|

Tang Dynasty pottery Kunlun slave dancer, unearthed in Xianyang city, Shaanxi province. Photos Provided to China Daily |

During his lifetime he was known as a Kunlun slave.

"Kunlun in this context means black," says Ge Chengyong, one of China's leading historians.

"Some of my peers and predecessors have thought that these dark-skinned people, with curly hair, broad nose and thick lips, hailed from Africa. I believe they are more likely to have come from Southeast Asia, for example the Indonesian archipelago.

"Between the fourth and sixth centuries, to which the figurine has been traced, the trade route between China and Africa merely connected the Chinese empire with Egypt. So there is a very slim possibility that these men came from the heart of the African continent. On the other hand, words about them, albeit scant, appeared in writings of the time in which they are portrayed as 'wearing shorts and being superb divers or fast mast-climbers'. These are traits associated with islanders from Southeast Asia."

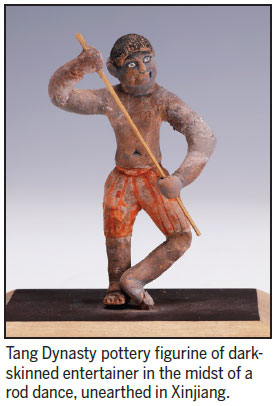

In fact, very little is known for sure about these "slaves", who are believed to have enjoyed a social status much higher than their designation suggests. These days their images appear as typical Tang Dynasty (618-907) polychrome ceramic figurines. Some are semi-naked, the lower part of the body wrapped in knee-length loin cloth, their signature dark skin shimmering under dim museum light.

But two things are beyond dispute. First, they entered the lives of the Tang people in an intimate way, attested to by the abundance of portrayals in pottery from Tang era tombs. Second, their arrival in large numbers in Tang China was made possible by the fast development of the ancient Silk Roads, including the terrestrial route and the maritime one.

The terrestrial one, the most famous, is composed of a network of trans-Eurasian trade routes connecting the Chinese heartland with the Eurasian steppes, the Mediterranean countries and the Indian subcontinent. The maritime one linked China to Japan and the Korean Peninsula to the north and Southeast Asia and Africa to the south.

"Some of these men may have been purchased - or captured - by local tribal leaders or human traders from one of those Indian Ocean islands," Ge says. "From there, they could have traveled to what today is Vietnam before moving farther toward the heartland of the Chinese empire. Their existence in Tang China has cast a tantalizing beam of light on the society of their adopted home, although most details of that existence are likely to remain forever shrouded in mystery."

Ge says that the Kunlun slaves, along with other non-Chinese domestic servants, were so popular at the time that having them within the household became not only fashionable but de rigueur for the rich.

"It was a fashion and a fad that reflected a general fascination with things exotic, a fascination that gripped all of society."

That was more than half a millennium after the initial opening of the terrestrial Silk Road, by a man named Zhang Qian, between 139 BC and 126 BC. Over the following centuries, a great miscellany of people traveled on Zhang's road, while having it constantly extended and expanded. Frequent cultural and commercial exchanges ignited the interest of the Chinese toward the outside world, and the sparkle turned into a bonfire during the era of Tang.

The Kunlun slaves were seen less as domestic servants and more as the embodiment of a foreign land, one which their masters could only imagine.

They didn't only dazzle with their crowns of curls. A Tang Dynasty pottery figurine unearthed in Xianyang, a little more than 20 kilometers north of Xi'an, in present-day Shaanxi province, captures a Kunlun slave performing a dance. His torso is twisted, the palm of one hand faces down, the other hand is raised in a tight fist, and he wears a beaded necklace, bangles and rings. You get the feeling that no banquet would have been complete without a few of his dynamic moves.

In another equally vivid rendition, a black teenage boy, half-naked, does a rod dance. Yet more moving than the dance gestures are his well-proportioned body, supple skin and youthful elegance, enhanced by palpable athleticism. Both images were on display at a previous Silk Road exhibition in Hong Kong to which Ge was a consultant.

"They could be entertainers or even acrobats," he says.

Yet despite their popularity with their clientele, the Kunlun slaves were far from the only group of people who were traded along the ancient Silk Road, says Rong Xinjiang, a professor at Peking University and a Silk Road researcher.

Rong makes the comment as he points to a paper sales contract for a slave, unearthed in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region in Northwest China. The contract, written in neat, inky Chinese calligraphy, shows that a man named Zhang Zu bought a slave from a Sogdian merchant. The contract was signed in the year 447.

"For those familiar with the ancient burial traditions of the Chinese, the discovery is not surprising at all," Rong says. "People believed that they should take underground with them all the contracts signed during their lifetime, just in case of a dispute.

"Between the fourth and eighth centuries, the Sogdian people from West Asia dominated the terrestrial Silk Road. The things they sold into China ranged from elaborately wrought metal wares and exotic-smelling spices to rare animals and even humans. In many cases they traded their own people, especially young Sogdian boys and girls from poor families."

In fact, the Sogdians were "the biggest slave traffickers of the Silk Road", Rong says.

"During Tang, human trading was nothing unusual," Rong says. "Markets were available at almost all major stops on the ancient Silk Road, from Dunhuang, in present-day Gansu province, where some precious letters written in the now-extinct Sogdian language were discovered, all the way to Chang'an," Rong says, referring to present-day Xi'an.

However, Rong stresses that with Tang being an open feudal society, these men should not simply be depicted as slaves.

"Of course they could be bought and sold, and their freedom, consequently, was severely curtailed. Yet these Sogdian people, distinguishable by their high-bridged nose and deep-set eyes, were treated far better. Let's not forget that in a society where things foreign were not just tolerated but celebrated, their masters bought them not for manual labor but to showcase wealth and a trendy life-style."

In other words, they were not necessities but accessories.

And the fact that many Sogdians were expert dancers must have certainly helped when their masters held a banquet to entertain guests. Their signature electrifying leaps and bewildering twirls were expected to set everyone in a mood for carousal.

"Despite their different origins, all of these men were either involved in regular exchanges with ancient China, or became part of it, thanks to the Silk Road," Rong says. "And they collectively held up a giant mirror to the Chinese empire, extremely open and highly hierarchical at the same time."

The ceramic boy, for his part, may have been a little too tired or homesick to reflect on such matters. He was discovered in a suburb of the city of Luoyang, about 400 kilometers east of Chang'an. (Luoyang was the capital for the Han Dynasty between 25 and 196. Later, during the reign of Tang, the city prospered once again, gaining for itself the title of the empire's "eastern capital" - as opposed to Chang'an, its western and official capital.)

The boy came in between those two periods. The statue has been dated to between the fourth and sixth centuries, a time in Chinese history marked by war, fragmentation and, surprisingly, art flourishing and rapid cultural development.

The sense of quietness he exudes contrasts with the color and cacophony of the time and place in which he found himself. In the ensuing centuries, it would be a color and cacophony added to by those who followed in his footsteps.

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 06/01/2018 page22)