Landmark meeting of two cultures

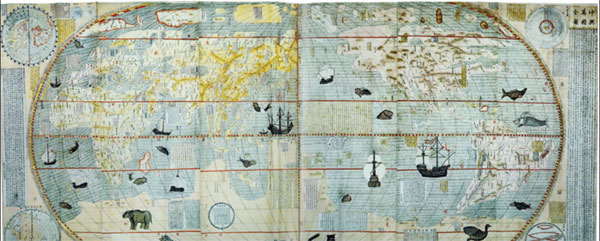

Zhang Xiping opened a map in front of him. Against the pale blue background were blocks of whitish yellow, depicting land masses (or the continents, if you like). Mountains were suggested by dabs of brown, and there were black icons representing ships on the high seas, and depictions of animals, with many of those on the lower part of the map having a grotesque appearance.

The ships bring to mind the Santa Maria of Christopher Columbus, but the animals, one featuring spiky wings like those of a pterosaur, seem to be a product of the cartographer's imagination.

"A map is an expression of a world view," says Zhang, a scholar at Beijing Foreign Studies University who specializes in cross-cultural exchanges between China and the West.

|

The world map painted by Matteo Ricci during his stay in China. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

Ming Dynasty Emperor Chongzhen (1611-1644). |

|

The gravestones of Western missionaries on the campus of the Beijing Administration Institute. |

|

Left: the gravestone of Matteo Ricci. Right: the stone relief on the base of a gravestone. |

"By drawing up this map, the author, the Italian Jesuit missionary-cum-adventurer Matteo Ricci, had expected to put China - and members of its elite society - into perspective."

If that is the case, then the Italian, who traveled to China around 1582 and is believed to have been the first Jesuit missionary to set foot in Beijing, in around 1601, succeeded to a certain extent.

The map probably played a crucial role in the conversion of Xu Guangqi, a Chinese scientist and politican whom Ricci befriended and who saw the map.

"For this man, who was steeped in traditional Chinese teachings of literature and morality, the map must have greatly undermined many of his preconceptions. The belief he had held of 'a round Heaven and a square Earth' was shattered, together with all the sense of pride and superiority well-educated Chinese during the Ming time were taught to harbor toward their lesser mortals - the barbarians from outside the Middle Kingdom, Ricci included," Zhang says.

However, "converted" may not be the right word, Zhang says at the same time.

"A Catholic Xu made no effort to relinquish his own cultural and ethical upbringing, an upbringing largely informed by Confucianism, the dominant philosophical thinking of Chinese society, even now," he says.

"In fact, the opposite was true: Xu was persuaded to join the fold because he saw no apparent contradiction between Catholicism and Confucianism," Zhang says.

"The picture Ricci revealed to him through the prism of Catholicism called to mind the one he already had in mind - the Chinese version of a utopia that people could arrive at one day guided by the good teachings of Confucianism."

If anything, the relationship formed with Ricci, whose footsteps other Jesuit missionaries followed between the early 17th century and late 19th century, is telling.

"Added to the lasting friendship that ended only with Ricci's death in 1610 is a mixed dose of mutual attraction and admiration, compromise and - possibly - condescension. In a sense, the same words could be said of the entire Jesuit mission and its mixed reception during the two Chinese dynasties of Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911).

Li Xiumei, an associate law professor at the Beijing Administration Institute, says that while Jesuit missionaries who were pragmatists demonstrated a high level of tolerance toward Chinese traditions and customs - a man needed not to banish his idols in order to convert - Chinese scholar-officials such as Xu also did their fair share of self-persuasion.

"Some succeeded in convincing themselves that becoming a Catholic in no way impinged on their core identity as a Confucian, since Christianity could be used to supplement Confucianism, and to restore to China what was originally theirs and their best," Li says.

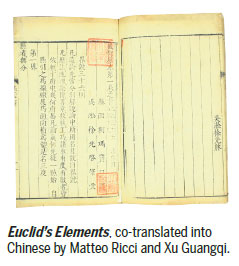

Xu, who with Ricci translated the first six books of Euclid's The Elements into Chinese in Beijing around 1607, a few years before Ricci died, made this observation in the preface he wrote for their co-effort.

"He's not making unfounded assertions," Li says. "Historical evidence shows that the ancient Chinese once gained certain scientific knowledge, which was lost by the end of the Ming Dynasty. One example involves the algebra that appeared around the first millennium, during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). By the time the Jesuits arrived, certain writings concerning the topic still existed but were no longer understood in China, not even by its brightest brains."

In other words, from a Chinese perspective, Western learning, as often personally embodied by Ricci and his equally talented and determined followers, had an origin that is decidedly Chinese. By taking up their religion, Xu and like-minded Chinese were trying actively to rediscover and recover what had belonged to their ancestors.

In part due to the fact that some of these Chinese occupied important positions at court, the same type of thinking inevitably seeped through the high walls of the royal palaces to reach men at the top.

Although the inner workings of Emperor Chongzhen, the last emperor of the Ming Dynasty, will forever remain unknown, it is believed he was on the verge of being converted to Christianity before having second thoughts. (But those who came after him did: After the fall of Ming and the suicide of Chongzhen in 1644, some royal descendants and their supporters fled to the country's south, where they set up the Southern Ming regime, which lasted for another 39 years. There were princes from Southern Ming who took up the religion.)

After the founding of Qing, China's last feudal empire and one set up by the minority Manchu people (China's majority ethnic group is Han, to which the Ming emperors belonged), the Jesuit missionaries enjoyed a honeymoon period with the new rulers. Little wonder, Zhang says.

"The Qing emperors, coming from a culturally backward background and not so confident about ruling over their more sophisticated subjects, turned to the missionaries as a secret weapon. Emperor Kangxi of Qing did use the cannons designed by Jesuit missionaries to repel his foes.

And remember, the key to retaining a secret weapon is to keep it secret. That explains the attitudes of several Qing rulers toward the missionaries: The knowledge and services of these foreigners were appreciated and even employed to fulfill the fantasy and ambition of a few, but never adopted on a large scale."

"Everything advanced - technology or anything else that the Western missionaries brought to China - did not get a chance to have a real, long-term impact," he says.

In 1792, on the 80th birthday of Emperor Qianlong, grandson of Emperor Kangxi, the British government sent its first official envoy to China, led by George Macartney. "After the emperor bluntly refused his request for the Qing court to open its ports on the grounds that his empire had everything and therefore had no need to trade, the envoy observed that the glory of the Middle Kingdom belonged to the past," Zhang says. "He was quite right".

Within no more than 50 years, the Western powers were pounding on China's long-closed doors. The warfare and the resulting unequal treaties that the crumbling Qing empire was forced to sign in effect turned the missionaries into agents for colonialism in people's imagination, which sometimes was true. They became objects of hate in a land their predecessors had come to preach in.

"Participants in the Boxer Rebellion destroyed the gravestones set up for the earlier generations of missionaries," says Li, referring to the violent anti-colonial and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901.

These included gravestones that used to sit on the campus of Li's institute. Some of them still do today, although removed from their original location. There were 49 of them.

"From then until modern times, the tombstones were also subjected to the turmoil of China's 'cultural revolution' (1966-76), when, as symbols of imperialism, they were smashed up or buried," she says, pointing to the deep cracks that run through some of the stone monuments. "Many were lost forever, but what could be found were later restored and moved together on this specially designed lot in the late 1970s and early'80s."

On the barely visited corner of the campus the monuments stand, bathed in a kind of solitude quite uncharacteristic of their owners' eventful lives.

"If you look closely, you will notice that in some cases the base of a monument does not match the part that rises from it," Li says.

One of them belongs to Ricci.

"When he made that map during his stay in China around 1602, he drew up all those longitudinal and latitudinal lines that would later transform the millennia-old Chinese way of cartography," Zhang says. "And then he put the land mass that was mainly occupied by China in the center-left, highlighted in yellow."

zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 03/02/2018 page1)