Tot learning turns into big business

Private investors rush into booming sector amid quality concerns

Rising demand in China for top quality, early-stage education and an inadequate supply are prompting private and foreign investors to rush into the segment in the hopes of huge and rapid growth.

Shopping malls in big cities now house early-stage educational institutes that offer classes covering every conceivable subject, ranging from English language to arts.

|

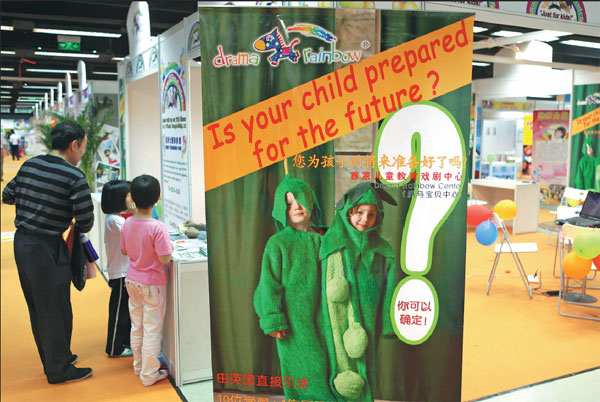

The booth of a drama school for kids, which hires foreign teachers for its courses, at a children's products and education exhibition in Beijing. Provided to China Daily |

Some even advertise imaginatively titled courses like "early-stage cognition cultivation" and "multiple potentials and personality development".

In the past few months, however, alleged abuse of children at some kindergartens and early-stage educational institutes in Shanghai and Beijing have led to a serious review of the situation, further stoking the demand for better, safer services in the segment.

At the annual Central Economic Work Conference in December, the leadership took stock of the situation and sought to make child care and early-stage learning safe, secure, orderly and affordable.

That's because courses that are currently offered tend to be rather expensive.

For example, a 45-minute class at Romp N' Roll, an early-stage education center in Beijing, can cost up to 299 yuan ($45; 38 euros; £34). From 50 to 150 such classes constitute a course, so a course could set back parents by up to 45,000 yuan.

Even so, such courses are few and far between. Demand far outstrips supply.

According to a report from Qianzhan Industry Research, the early-stage education market is still nascent in China, with 2017 sales revenue expected to top 200 billion yuan.

"Since married couples can now have a second child, there will be about 3 million to 5 million newborns annually, so the market potential will rise by 90 to 150 billion yuan every year," says Wang Huainan, founder and chief executive officer of Babytree Inc, an internet-based company in Beijing.

"According to our research, 80 to 90 percent of families would like their kids to receive early-stage education. However, only 15 percent of families are able to do so," says Wang.

"Location is one big reason," he says. "Those institutes are usually located in shopping malls. Imagine you are a full-time working parent. Who has the time to send the kids constantly back and forth to a mall and wait there?"

Starting as a maternal website, Babytree Inc has grown into an online forum for a large number of new moms. Typically, they discuss concerns, and the shortage of top quality early-stage educational institutes figures in their list.

To remedy the situation and wrest market share through early mover advantage, private investors, including some from Silicon Valley, are making a beeline for the segment.

Michael Moe, founder of Global Silicon Valley, a US-based education and technology investment bank, says: "China's education business, especially the potential in the early-stage segment, is frequently talked about. In China, you don't need to worry about the market size."

Global Silicon Valley is the venture capital company that backed Coursera, the world's largest free online education portal.

Moe says investors in Chinas' early-stage education market need not worry about returns because domestic demand is strong. Global Silicon Valley, he says, is considering investing a "significant sum" of money in China soon.

"Asian parents spend seven times more money on their kids' education than American parents do," he says.

Yu Wenjie, 30, a Chinese medicine doctor who is expecting her first child shortly, has already started to plan the kid's future.

"It's OK that early-stage education is expensive," says Yu, who works at a hospital in Ningbo, Zhejiang province. "But I think what they teach at such institutes is rather shallow, and I just won't buy those so-called full-brain potential development courses."

Wang of Babytree Inc says, "We found that among those 15 percent of families whose kids receive early-stage education, 80 percent are not very satisfied with the quality."

That may be due to the fact that expensive bilingual courses are usu-ally delivered by ordinary Chinese and foreign teachers.

A 35-year-old Dane working with a bilingual early-stage education center in Ningbo, who asked to be identified only as Chris, says he would rather describe himself as a world traveler.

"To be honest, I'm in the middle of my journey exploring the world," he says. "But one day, they just stopped me in the street and offered to pay me a fat check.

"So, I'm staying here to teach English for a year. My first language is not even English! This may sound like a little bit of an exaggeration, but basically all I do every day is sing Old MacDonald Has a Farm."

Since early-stage education is not part of the country's compulsory education system, industry insiders express concerns over lack of regulation, particularly with regard to teacher qualifications.

"Driven by the profit motive, many speculators, whether qualified or not, rushed into the industry to take a bite of the large cake," the Qianzhan report says. "Meanwhile, the industry doesn't have standards for the market entry permit, teacher qualifications and curriculum design."

Nonetheless, the market is expanding and more problems are surfacing. A shakeout is inevitable, the report says.

It also says the internet will play an important role in the segment's evolution. Some online companies have already taken steps in this direction.

Babytree believes that a possible way to improve the quality of such education is to pay teachers more.

"I've heard of the recent kindergarten abuse scandal and the problem is that those teachers are underqualified," Wang says. "According to my observation, those Chinese early-stage learning teachers are usually underpaid, which has to some extent affected teaching quality.

"It requires us to think out of the box as we need to raise revenue in order to pay them more, for example, by making the education center more than a place just for kids."

Wang says that in the future, early-stage learning centers need to be places with retail functions for parents to socialize. In fact, Babytree has already worked with Mattel Inc, the world's largest toy maker, to launch a child play center this year where parents can relax, socialize and shop.

Connecting users and teachers through the internet is another way to solve the imbalance in the distribution of educational resources, industry observers say.

Targeting children ages 4 to 12, VIPKid, a Chinese online startup engaged in English-language education, has managed to link its teaching resources in North America with children in China and elsewhere around the world.

"As a teacher myself, I realized it's impossible to provide tailor-made education if you have 50 to 60 students in a classroom at a time," says Mi Wenjuan, founder of VIPKid. "But one-to-one online education can make it possible."

By connecting teachers and students through the internet, VIPKid provides a convenient way for parents to connect with teachers who are native language speakers.

renxiaojin@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 01/19/2018 page28)