Family tree roots go deep

Genealogy tourism grows as more overseas Chinese return to seek clues to their identity

Before the Chan family left, they locked up their home and handed the keys to their neighbors, the Situs, to keep an eye on things. If the Chans' descendants should ever return to the village of Chikan (赤坎 chìkǎn) from overseas, the Situs would be there to open the door.

Thirty years later, Huiying Bernice Chan, a New York anthropologist of Chinese descent, arrives at her grandmother's old home the day after Qingming, or Tomb Sweeping festival. After seeing Chan's photos proving she is related to the former neighbors, Mrs Situ fishes a key from a drawer. Mr Situ himself arrives a few minutes later, beaming.

"Sure, I remember the grandmother," he says as he unlocks the door. "I remember all the family. I was very small, but I lived right here. They went to America, didn't they? It was a very long time ago."

Kaiping, where Chikan is located, is part of a region known as the Five Counties (五邑 wǔyì) in Guangdong province, about 100 kilometers southwest of the metropolises of Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Together, the counties make up one of the biggest of what's known as the qiaoxiang (侨乡 qiáo xiāng, overseas homeland) in China. These communities are dotted across China's southeast coast, from Fujian down to Guangdong's Teochew region, the booming Pearl River Delta, then west as far as Zhanjiang near the island of Hainan. Starting from the mid-19th century, poverty and war forced these communities to cross the sea for survival. Young men set out to work in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, the Americas and Australia, sending their earnings home and eventually calling for their families to join them abroad.

In many ways, however, the identity of qiaoxiang has less to do with who left, as who comes back. The countryside around Kaiping is dotted with diaolou (碉楼 diāolóu), colonialstyle watchtowers, UNESCO World Heritage sites that were featured in the 2010 action-comedy movie Let the Bullets Fly, filmed just off Chikan's main street.

Fusing Chinese and European architecture, these fortresslike diaolou were built by those who wanted to use wealth accumulated overseas to protect their family's property from bandits. Signs on local schools, parks, hospitals, even a farm, bear the characters for "overseas Chinese" (华侨 huá qiáo) rather than the usual "people's" (人民 rénmín); some were built decades ago, but most are sponsored by diaspora groups, who make return visits for ribbon-cutting ceremonies and the occasional Spring Festival. And in almost every village in the Five Counties, there are families like the Situs, who preserve stories, memories and sometimes a physical home to show descendants of overseas Chinese should they ever come looking.

"It was incredible; I was always under the impression that we had lost contact," Chan says after visiting one of her ancestral villages. "But they were very up-to-date with information about my family. They knew about who passed away, and how. That's what amazed me - the bond that's kept between villages around the world."

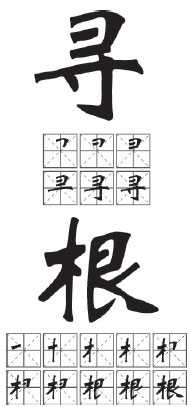

In Chinese, the most common words for these kind of journeys are 寻根 (xúngēn, root-seeking), 寻亲 (xúnqīn, relative-seeking), or 返乡 (fǎnxiāng, returning to the home village). None quite tell the full story. Overseas Chinese may simply be curious to see a place they've often heard mentioned, without being sure there are records or relatives left to find. Most don't intend to "return" permanently, and many don't linger in the ancestral village itself more than the time it takes to snap some photos.

Perhaps this is why the Chinese terms are often paired with (lǚ, travel), denoting travel or tourism, as in 寻根之旅 (xúngēn zhī lǚ, root-seeking travel), while in English, these journeys are sometimes referred to as "genealogy trips" or "ancestor searches", conjuring up images of poring over genealogy databases so that one can claim descent from Charlemagne at a dinner party.

As straightforward as this seems, there are obstacles. One would need to know enough about China and the Five Counties; language skills in both Mandarin or a local dialect are vital as well, as websites are only in Chinese and few staff members speak other languages.

Unlike Chan, who arrived with the names of all four grandparents' villages in a notebook and was fortunate to find neighbors who'd kept in touch, most "roots seekers" have far rockier starts.

Some descendants may not know anything, other than that relatives were once Chinese. Two sisters, Eunice and Jing Yi Beh, third-generation Malaysian-Chinese, say that their grandfather never shared any details about his former life, possibly due to painful experiences. The only clue was the name of a village engraved on his tomb, a Chinese burial custom for those who've died overseas.

Arriving in Yangkeng village in Puning, Guangdong, the Beh family found that there was no one left who could recall anything about their branch of the family. Even being shown the village's copy of their clan's genealogical records, or zupu (族谱 zúpǔ), proved to be disappointing, as it only went back to the generation after their great-grandfather's.

"So we just saw our clan's ancestral temple and asked the village official to spread the word on WeChat that we were looking (for relatives); he hasn't heard from anyone yet," Jing Yi Beh says, a year later. "Instead, I've found all of his relatives that he asked me to look up in Malaysia." The only thing the family could do was sample the local food, says Beh; that, at least, tasted like home.

A best-case scenario is documented in All Our Father's Relations, a Canadian documentary that had its overseas premiere at the Beijing International Film Festival in April. In it, four siblings of the mixed-race Grant family visit their father's home village near Zhongshan in 2013. The Grants discover an uncle they never knew about, meet the daughter left behind by another uncle who'd emigrated to Canada, and are shown pictures of their ancestors decorating the walls of their great-grandfather's house.

"I was told, 'You are the 17th generation of this house,'" Larry Grant told the Vancouver Courier afterward. "'Oh, my God.' That was my reaction."

Yang Shereng, a researcher affiliated with the overseas association in Toisan (Taishan, 台山 táishān), another of the Five Counties, says, "Every person in the world, of any ethnicity, any skin color, has some yearning to know where they come from." Yang has had clients who have searched fruitlessly for 10 years, armed with just family lore that "the village their great-grandfather left 200 years ago had a well in front of an ancestral temple in front of a hill." Other clients arrive with detailed information, only to find the ancestral home razed, the victim of either natural disaster or urban development.

"Not everyone is lucky enough to find relatives," Yang says. "It has been too many years, lots of villagers have migrated, and older people who had memories of their family have passed away."

But when all the pieces fall into place, whether through luck or perseverance, the experience is "miraculous," says Yang.

Having visited her family home, Chan is now hoping to locate all four grandparents' zupu and trace their history back 100 generations. In Chikan, she visits the library of the Guan clan association, where the genealogists are working on a family tree of the male members of her grandmother's clan. As the elderly researcher flips through the thick tome, fathoming a path through the sprawling lines and unmarked pages, there's a moment of recognition. "My family," Chan points suddenly at a page.

A moment later, she has her own notebook open on a page with the names of current relatives, which the researcher is adding to the ancient tree, penciling new names in margins and leaves that have been waiting for them all along.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com.cn

The World of Chinese

|

The picturesque waterfront of Chikan is a popular stop on the itinerary of overseas returnees. Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 07/21/2017 page23)