Of cabbages and things

The names of many foods and other objects in Chinese are evidence of the culture's rich history of cross-border trade

It's said that in the age of outsourcing, globalization and supermarkets, people no longer know where their stuff comes from. Not so for the ancient Chinese. In their day, as increased trade across the empire's borders brought new foods and other objects into their daily orbits, the Chinese invented names for these novelties.

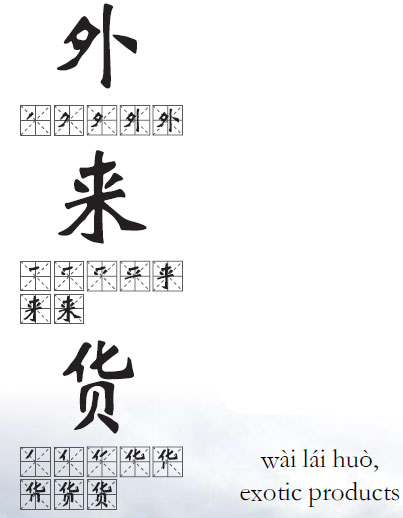

These names helped exotic objects assimilate into ordinary life while preserving the distinction of their very foreign roots, as well as the exact nature of China's foreign relations during the historical period in which they were introduced.

There is a rich and venerable tradition in ancient China for categorizing and labeling people and objects of foreign origin. According to writings from the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC), the Chinese civilization from the very beginning conceived of itself as people who lived in the "Central Plains"(中原 zhōng yuán), and surrounding them were ancient regions and tribes whom they identified by the names of 羌 (qīang), 胡 (hú), 蛮 (mán), 夷 (yí), 戎 (ròng), 狄 (dí), 羯 (jié), 越 (yuè) and 番 (or 蕃, fān). These were later simplified as 夷, 戎, 狄, and 蛮, referring (respectively) to the tribes that lived in the east, west, north and south of the Central Plains. Then, as successive waves of imperial expansion and trade brought the Chinese in contact with even more distant peoples, the characters 胡 (hú), 番 (fān), 洋 (yáng) and 西 (xī) came to be associated with these foreigners and the exotic products they introduced.

Although over time many of these characters denoting foreignness came to be used pejoratively, they are not necessarily xenophobic, and they survive today as prefixes in the names of various objects in our daily conversation. Take, for instance, the character 胡 (hú), which typically referred to people and objects that came to China from western or northern regions through overland trade on the Silk Road routes from the Han to the Tang dynasties. Supposedly, the name is derived from the beards (胡须, húxū) sported by these western and northern residents who, in the Tang Dynasty especially, were arriving en masse to trade and settle in the capital, Chang'an (Xi'an), and elsewhere across China. Many of these so-called Hu people (胡人, húrén) became successful merchants, artisans, entertainers and scholars; they brought to China their religious beliefs, such as Buddhism and Nestorianism, and some were even the ancestors of famous emperors.

Traces of their influence survive in the Chinese language today through words such as 胡萝卜 (húluóbo, carrot, literally "foreign radish"), which came to China from the Afghan region supposedly through the western expeditions of Han Dynasty general Zhang Qian; 胡椒 (hújiāo, black and white pepper, "foreign pepper") and 胡瓜 (húguā, cucumber, "foreign melon", also known as 黄瓜, huángguā), originating from India; 胡麻 (húmá, sesame, "foreign flax", also known as 芝麻, zhīmá), from Africa; 胡豆 (húdòu, broadbean, "foreign bean") from the Mediterranean; and 胡桃 (hútáo, walnut, "foreign peach", also known as 核桃, hétáo, or 羌桃, qiángtáo), originating from Persia and also brought to China by Zhang Qian. There are also the instruments of the 胡琴 (húqín, "foreign zither") family, which came from the peoples of the steppes northwest of the Central Chinese Plains. Consisting of fiddles with a cylindrical or hexagonal body and a long tubular neck, the most famous member of this instrument family is the two-stringed 二胡 (èrhú)), which is sometimes translated as "Chinese violin" and is considered one of the most iconic Chinese folk instruments today.

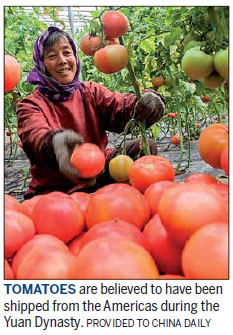

As waves of conquerors from the northern regions drove the seat of Chinese imperial power southward, maritime trade through the southern oceans gradually came to eclipse the ancient overland routes from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) onward. In the Song, Yuan and Ming dynasties, the Arabian and Persian merchants who dominated these trade routes, settled in their own communities along the southeastern coast of China and - at least during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) - were even appointed to official positions were referred to by the prefix 番, since the ships in which they arrived were called 番舶 (fānbó, "foreign oceangoing ship"). Their history is reflected in words like 番茄 (fānqié, "foreign eggplant"), which is what people in southern China today call tomatoes, a plant from the Americas that came to China via what they called the Southern Sea

(南海); 番薯 (fānshǔ, "foreign yam"), for sweet potato; 番石榴 (fānshíliu, "foreign pomegranate"), or guava. The Sichuan word for spicy red peppers

(海椒, hǎijiāo, "sea pepper"), the quintessential feature of local hotpot and other cuisine, uses the prefix 海 (hǎi, sea) to denote origin from the Southern Sea in the same period.

From the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) onward, direct contact increased between the Chinese, Europeans and North Americans, at which time the character 洋, or "ocean," came to denote anything introduced to China by these Westerners across the so-called "Western ocean" (西洋 xīyáng). This character is still commonly used to refer to anything Western today - such as 洋人 (yángrén, Westerners), a polite (albeit old-fashioned) way to refer to Western people, or the expression 崇洋媚外 (chóngyáng mèiwài, "worshiping the West, fawning over what's foreign"), which was the theme of education minister Yuan Guiren's speech in 2015 on the need to a resist the importation of "erroneous values from the West" to Chinese universities. Other terms associated with the 洋 include 洋葱 (yángcōng, onion, "ocean scallions"), 洋芋 (yángyù, potato, "ocean taro"), and 洋白菜 (yáng báicài, cabbage, "ocean bak choi"), as well as 洋烟 (yángyān, cigarettes, "ocean smoke"), 洋娃娃 (yáng wáwa, "ocean doll", referring to bisque or plastic dolls with Western features rather than those made with traditional Chinese materials and techniques), and 洋火 (yánghuǒ, matches, "ocean fire").

Similar to 洋, the character 西 (xī, West) also denoted products that came to China with these Western merchants, missionaries, and envoys in this period: There is 西红柿 (xīhóngshì, literally "Western red persimmon"), which is what the northern Chinese call tomatoes; 西葫芦 (xīhúlu, "Western gourd"), for zucchini squash; 西芹 (xīqín, "Western celery") for parsley; 西兰花 (xīlánhuā, "Western orchid") for broccoli; and 西洋镜 (xīyáng jìng, "Western ocean mirror") for zoetrope, an early form of cinema consisting of still images in a revolving cylinder. However, 西瓜 (xīguā, "western melon", watermelon), is not an example in this category; it came to China in the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and the 西 refers to 西域 (xīyù), the western frontier from which the Hu people also came.

There are a variety of other words that once carried the "foreign" prefixes but have since then lost them - as, for instance, 胡蒜 (húsuàn, garlic) and 胡葱 (húcōng, shallots), which are now known as 大蒜 (dāsuān, "big garlic") and 大葱 (dàcōng). Similarly, when most Chinese speak of all of these objects today, the "foreign" prefix isn't parsed separately, but rather is understood as a whole with the rest of the term as an ordinary Chinese word. Not bad for a bunch of foreign transplants.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 12/02/2016 page23)