A meaningful exchange

Certain expressions in any language seem designed to befuddle non-native speakers, and Chinese is no exception

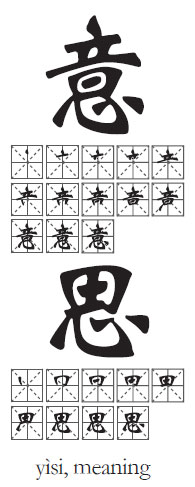

At some point in their careers, all learners of second languages come to suspect that some expressions are built in specifically to ensure that non-natives can never master them, like some prehistoric tribal way of sniffing out the intruder while also having a laugh at the person's expense. In Chinese there is the term 意思 (yìsi), which literally means "meaning", but, as it's commonly said in China, there are at least 10 meanings to meaning.

In some ways it's appropriate that "meaning" should be one of the most meaningful of Chinese words. As a so-called high-context language, spoken Chinese can be full of empty gestures and hidden politeness pitfalls that allow speakers to hint at their intentions without actually committing to them in the content of their speech. Accordingly, the word "meaning" itself has been coopted to hint at lots of things you're too polite to say but actually wish to mean. An old joke demonstrates it best:

An employee walks into his boss' office and drops off a red envelope full of cash.

1 . 领导:你这是什么意思?

lǐngdǎo: nǐ zhèshì shénme yìsi?

Boss: What is the meaning of this?

2.员工:没什么意思, 意思意思。

yuángōng: méi shénme yìsi, yìsi yìsi.

Employee: There's no meaning really, [it's a] meaning meaning.

3. 领导:你这就不够意思了。

lǐngdǎo: nǐ zhè jiù búgòu yìsi le.

Boss: Well, now, that's not enough meaning.

4. 员工:小意思,小意思。

yuángōng: xiǎo yìsi, xiǎo yìsi.

Employee: Small meaning, small meaning.

5. 领导:你这人真有意思。

lǐng dǎo: nǐ zhè rén zhēn yǒu yìsi.

Boss: You have so much meaning.

6. 员工: 其实也没有别的意思。

yuángōng: qíshí yé méiyǒu biéde yìsi.

Employee: Actually, I didn't have any other meaning.

7. 领导:那我就不好意思了。

lǐng dǎo: nà wǒ jiù bùhǎo yìsi le.

Boss: Then it'll be "difficult for me to mean".

8. 员工:是我不好意思。

yuángōng: shì wǒ bùhǎo yìsi.

Employee: No, it's me who finds it "difficult to mean".

Still with us? Here's a categorical breakdown of the possible meanings you could use "meaning" to mean, in the order in which they appear in the joke.

1 - Literally, "meaning", what an action denotes or symbolizes. The boss is suspicious of why the employee is handing him cash out of the blue.

2 - Appreciation, a gesture of respect. The employee protests that there's no intention to bribe or hint at anything, that his action was meaningful for meaning's sake; however, a person who says this usually does have some ulterior motive - as the old saying goes, he does protest too much, and 意思意思 ("meaning meaning") can be a socially coded way to hint that you're giving a person some material benefit without being so crass as to mention it. It's a must-have expression for all corrupt officials.

3 - Intimacy, frankness. This is the most difficult "meaning" of the bunch. The way it's used in this joke is the boss ribbing the employee that he's selling himself short, a tongue-in-cheek way of saying that they're such good friends that the employee doesn't need to be making him respectful offerings. It also hints that the boss knows the employee isn't just handing out cash for nothing, but they're such good friends that the employee should have just come right out and ask what he wanted. While this joke uses an ironic version of 不够意思 (bú gòu yìsi, "not enough meaning"), you can also use it the normal way - for instance, if a friend in your group doesn't pay their share of the bill, or if anyone betrays your trust in any way, then they're 不够意思.

4 - Care, an action or token into which someone has put some effort and concern. Similar to 2, but this puts emphasis on the concern on the giver's part rather than the meaning it holds for the receiver. Here, the employee is protesting again that the gift is just small potatoes on his part.

5 - Interest, amusement. To say that a person or thing "has meaning" is to say they intrigue you in some way. Here, the boss is amused by his employee's protests.

6 - Motive. The employee protests a final time (see a pattern?), saying that he had no ulterior motive.

7, 8 - Part of a phrase that makes apology for your rudeness. The two final uses of "meaning" both have this meaning, used within the phrase 不好意思 (bù hǎo yìsi) in two different ways. The phrase literally means "it's difficult to mean", and can be literally interpreted as the speaker saying they've been put (or put themselves) in a position where it's hard for them to muddy their intentions, which is awkward and embarrassing because, hey, that's what we've been trying to do this whole time by abusing the word "meaning" in various ways. In this joke, the first instance of 不好意思 is the boss telling the employee he'll accept the gift ("Please excuse my rudeness, I will help myself".). The second instance is the employee apologizing ("No, it's me who should be embarrassed!") as a way of making sure the boss isn't humbling himself too much, saying that the gift was too small and not deserving of so much respect.

Another example:

Many weeks ago, a high school principal in Shaanxi province caused an uproar when he told the graduating class that their parents should make a donation of hundreds yuan to the school, an incident which makes full use of the various meanings of "meaning". According to local media, the principal framed his request as, "the teachers have toiled on your behalf for three years, so why don't you 意思意思?" Students and parents who saw this for the money-grab it was, however, retorted that the principal was 不够意思 - that is, he betrayed the social contract between them, by which the educator is supposed to selflessly educate the student and model good social behavior.

Other uses:

You thought that was all? Actually, the above joke and Shaanxi donation scandal only grazes the surface of everything you could use "meaning" to mean (or not mean). For example, there is the phrase 真没意思 (zhēn méi yìsi, literally "really meaningless"), which is similar to the version of 不够意思 that the boss uses in the joke. It expresses the feeling that someone didn't consider you as good a friend as you considered them, hence they're being overly polite or distant toward you. It can be used either as an actual complaint or in a complimentary way, as in telling someone that they don't have to be so kind.

The expression 好意思 (hǎo yìsi, literally, "easy to mean") is essentially the opposite of 不好意思, signifying a complete lack of embarrassment. You use it to express your displeasure and outrage that someone is crass enough to do a certain impolite, dishonest, or just generally shocking thing, such as 世界上有那么多人没饭吃,你还好意思浪费粮食? (Shìjìe shang nàme duō rén méi fàn chī, nǐ hái hāo yìsi làngfèi liángshi. "There are so many starving people in the world, you're not embarrassed to waste food?").

意思 can also refer to certain trends or signs that something is about to happen, and in this case it's not just people who can "have meaning". For example, 天阴了,有点儿要下雨的意思。 (Tīan yīn le, yǒu dǐanr yào xiàyǔ de yìsi . The sky has darkened, maybe it means to rain.)

Finally, there's another use of 有意思 (yǒu yìsi, "to have meaning"), only in this instance you don't say that someone else "has meaning" (i.e. is interesting), but that one person "has meaning" toward another person.

Just to make things more difficult, all of these phrases with "meaning" in them can change their meaning slightly depending on who is speaking to whom and in what social context - such as we saw with the difference between 不够意思 in the joke and in the Shaanxi scandal. Another way to look at it is that "meaning", literally, is the cue that forces you to look into the context, politeness register and intentions imbedded in your conversation.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 11/18/2016 page23)