Shaolin culture packs a punch

Updated: 2016-10-14 07:34

By Satarupa Bhattacharjya and Qi Xin in Dengfeng, Henan province(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

Inside a large hall of the lush Shaolin Temple in Central China, the stage is set. The arc lights are switched on and a few chairs laid out in a neat row. The place echoes in the collective hum of people's voices. Young monks in shaven heads and gray robes gather in a corner of the room.

The heavy rains outside lash at the trees of a compound that is thought to have a 1,500-year-old history. A stream noisily gushes out to meet a river in the foothills of the Songshan Mountain.

A sudden quietness then engulfs the hall as its main door is flung open to allow the abbot Shi Yongxin to walk in. A delegation from a martial arts school in Japan and dozens of other visitors follow him to an area in front of the stage. After Shi Yongxin and his main guests are seated and the rest remain standing, the kung fu presentation begins.

|

Zhao Wenzhuo, a Chinese film star, performs kung fu at the Shaolin Temple's Pagoda Forest. Chen Wei / China Daily |

|

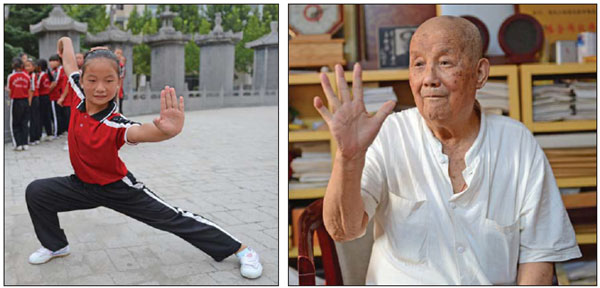

From left: A girl practices martial arts at a kung fu school run by Liu Baoshan; Kung fu master Liu Baoshan founded his first school in 1978. Today it is one of the largest near the Shaolin Temple. Photos by Xiao Mingchao / For China Daily |

|

Shaolin monks perform martial arts during a public performance in Putian, Southeast China's Fujian province. Reuters |

Thirty of Shaolin's finest monks show their skills - slicing the air with their fists and feet. A group of foreign male trainees join in. But unlike movies made in Hong Kong and Hollywood, there is no music accompanying their rapid moves. The practitioners only make a few signature sounds of the wushu (martial arts) vocabulary.

The show in Dengfeng, a city in Henan province, mesmerizes the onlookers, who let out loud gasps, much to the amusement of the resident monks.

But how relevant is this ancient culture outside the gates of the Shaolin Temple and Monastery?

Senior executives of Shaolin, students, tourists and representatives of the Taguo martial arts school in Dengfeng say that Shaolin continues to influence many in today's world.

The discipline, which combines Chinese Zen Buddhism with martial arts, is believed to have been started by an Indian monk named Bodhidharma, who came to Henan in the sixth century. The temple describes him as the first of six "patriarchs" of the monastic order. Chan, the Chinese word for Zen, was derived from the Sanskrit word dhyana, or "meditation".

The institution thrived in imperial China, especially during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), but kung fu was banned in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) as the royals feared a coup by the "warrior monks". Then, in the days of the Republic of China, the temple was set ablaze in 1928 by a warlord. Shaolin was dealt another blow during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76).

Its revival came in the 1980s and '90s on the heels of China's economic reforms. The buildings were rebuilt with private donations and government grants.

"Shaolin advocates health, justice and wisdom," says Wang Yumin, who heads the foreign affairs office of China Songshan Shaolin Temple, adding that the culture is passed down generations.

"The temple can be demolished but the spirit can't," he says of Shaolin's survival through the ages.

Soft-power export

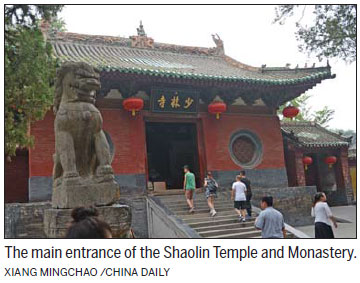

Russian President Vladimir Putin, the first foreign leader to visit the temple in 2006, has unwittingly become an ambassador for Shaolin. His photos are displayed by vendors at the building's entrance that has a lichen-lined facade with animal figurines on the top. Of the 72 basic kung fu techniques, some mimic the movements of five animals.

Many foreigners enroll at Shaolin each year to learn kung fu, paying about 6,600 yuan ($980; 880 euros; 790 pounds) a month, which includes food and lodging, for courses from weeks to years. But one of Shaolin's major sources of income is tourism, that provides some 250 million yuan in annual revenue.

Most foreigners tend to be in their early 20s who come with prior kung fu knowledge acquired in their native lands. Women make up a small percentage of the foreign students. A person needs at least five years of regular training to achieve a degree of proficiency in the discipline.

Diya Chalwad, a 10-year-old student from Mumbai on India's west coast, says her interest in kung fu sprung from gymnastics. Proudly exhibiting what she's learning, she says she will be here through February. At a good age to begin kung fu, she is the youngest foreign student on an ongoing residency program in Shaolin this year.

Her cousin, Harsh Verma, who is also from India, has been there for the past 18 months. Once a footballer with AC Milan's junior team, he now travels to other parts of China to perform kung fu along with Shaolin monks.

"I wanted to go to a place where there's a mix of physical and mental training," Verma, 24, says on the question of why he chose Shaolin.

The practice sessions are rigorous and can be physically challenging for women, but the final outcome of the training depends on an individual's attitude. That's how Daniela Murillo from Costa Rica sees it. The 26-year-old kung fu teacher from San Jose, the capital of her country, was on a recent short-term course.

"We're taking back of lot of fundamental stuff (on kung fu) from here."

In 2002, Shaolin Temple established a separate office to meet the demand for kung fu studies among foreigners, says Wang, who looks after that division. Today, there are Shaolin centers in the United States, Britain, other European countries, Australia and Sri Lanka. The temple doesn't have more overseas expansion plans just yet, he says.

And while kung fu's influence on popular culture, especially cinema, has waned in the recent past compared with its peak in the 1970s, when Bruce Lee made it world famous, Shaolin has sealed its place in modern history as a source of China's earliest soft-power exports.

'Keep going'

At its core, the order has 300 monks led by abbot Shi. He has been at the helm since 1999.

Young Chinese from different parts of the country are picked by the monastery through a test for the residential programs for kung fu and Buddhist studies. As the country's elite martial arts institution, Shaolin relies more on skills while screening students for the far fewer seats it has compared with other kung fu schools, including the dozens in Henan.

The monastery encourages the masters and disciples to maintain a disciplined lifestyle that doesn't involve the consumption of alcohol or meat. Monks aren't allowed to marry either.

"It is our fate that has brought us here," says Shi Yanfeng, 27. The monk came to Shaolin at age 15 from East China's Anhui province. Now a teacher, he sometimes goes abroad for the school's kung fu events.

Surrounding Shaolin Temple, some 40 martial arts schools have thrived in Dengfeng in the past few decades, with Tagou Education Group being one of the largest. Founded by kung fu master Liu Baoshan in 1978, it established its first school within 1 kilometer of the temple and today has six across the city.

Liu, now 85, says to perfect a taolu, or basic kung fu technique, follow the routine closely. He learned the skills from his father and grandfather. Liu's schools have 35,000 students where the male-female ratio is roughly 10 to one. Many of his former students have taught martial arts to the Chinese armed forces and police.

In one of his sprawling school campuses, hundreds of young boys and girls in red-and-black uniforms are seen practicing somersaults and other features of kung fu. Martial arts, once a dominantly male pursuit, is getting more attention from women these days. Guo Xiyu, 20, a female kung fu teacher at Taguo, says the reasons vary. "Some want to stay healthy, others to lose weight."

Hong Hao at Henan University say Shaolin kung fu has become a symbol of "national self-confidence", and public schools are trying to revive the popularity of martial arts in the country.

Back in a Shaolin courtyard, Chen Hao, 35, is found seated in the shade of a large tree holding his infant. He runs a decorations business in the city of Luohe, also in Henan. He and his friends have visited the temple earlier but this time he has returned with his family.

"Kung fu helped me understand that one needs to keep going at something to make it work," he says.

Contact the writers at satarupa@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 10/14/2016 page1)

Today's Top News

Xi: China considers Bangladesh important partner

Britain's May, faced with turmoil, agrees to a debate

Deals with Cambodia include energy, trade

Trump accused of inappropriate touching by women

China expresses condolences over death of Thai King

Chinese president arrives in Cambodia for state visit

Thai King, world's longest-reigning monarch, dies

Q3 trade growth rebounds, pressure remains

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|