Tea that is worth its weight in gold

Precious leaves are part of a culture that goes back 1,500 years in East China's Hangzhou

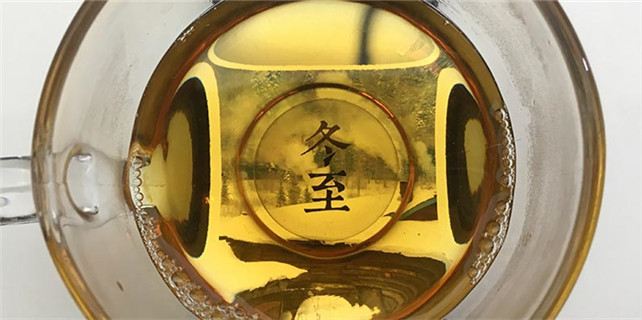

Longjing tea is green gold. In fact, premium leaves can be worth more than the precious metal.

Half a kilogram of top-shelf shoots sold for $28,000 in March 2012, when the equivalent amount of gold was valued at $26,680, China News Service reports.

|

People pick Longjing tea leaves in Hangzhou in March. Longjing is considered a cultural treasure. Li JianGang / Xinhua |

Low-grade Longjing sells for about 1,000 yuan ($150; 133 euros) for 500 grams, but at whatever price, Longjing, with its rich heritage, is considered a cultural treasure.

In Hangzhou, tea culture has roots that go back 1,500 years.

Its mystical virtues have been connected with Chan Buddhist meditation for centuries.

Emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) officially declared Longjing "imperial tea". His grandson, Emperor Qianlong (1711-99), reportedly bestowed imperial status on 18 bushes in Longjing village and brought their leaves to his ailing mother.

It is from these surviving trees that the most expensive shoots are picked in the settlement's Imperial Tea Garden.

They stand near the well from which Longjing takes its eponym, which translates as Dragon Well. The appellation hails from the ancient belief that the shaft was a portal to a dragon's lair, since it sustained the sole water source during droughts.

This history, or at least the lore, today enchants visitors attracted by Longjing's cultural cultivation.

The forested Longjing Street leading to the garden is skirted by plantations and studded with teahouses like Longyue.

Longyue's elderly owners earn 30,000 yuan a year from their tea fields and 20,000 yuan from the teahouse that also operates as a rural restaurant.

"We live well," Qi Yuzhen, 78, says. "We have no financial worries."

Visitors hail from around the world, says her husband, Li Rongtu, 85.

"They come to experience Longjing."

Yet establishments like Longyue offer insight into the lives of Longjing's farmers rather than into the high culture its tea brews.

Its allure is more rustic than refined. No ceremonies accompany ancient instrumental soundtracks by expert hosts in traditional garb. Those find homes along West Lake's downtown banks, where the cheapest cup of tea costs hundreds of yuan, compared with 15 yuan at Longyue.

Longyue hugs the road between the garden and the China National Tea Museum, the main thoroughfare for travelers to view the fields, witness production and go on picking tours.

At the museum you can find out about the beverage's social and scientific dimensions, with displays of early relics and the latest research.

The museum chronicles how tea drinking emerged from China's southwestern jungles as a medicinal concoction to become the drink of choice for the sophisticated and eventually the world's most drunk beverage after water.

This internationalization can be seen in downtown Hangzhou, where Martin Gamache, a Canadian, recently bought four boxes of Longjing to give hosts on his upcoming trip to Japan, plus one for himself.

"I think they'll appreciate it," he says.

The shop's owner, Fan Shenghua, is a provincial-level inheritor of the art of frying Longjing leaves. The procedure halts oxidation shortly after harvest, sealing in its botanical magic.

The skill was listed as a national-level intangible cultural heritage in 2008. The 56-year-old has been in the trade since he was 14 and aspires to rise to the national level by the time he is 60, when he would qualify for a stipend.

Certificates and competition trophies share shelves with boxes of Longjing. The packages are printed with quick-response codes that take customers to a website with an 11-digit authentication code, and information about the farm.

In Hangzhou, technology meets tradition for tea.

The Fan family line has grown and produced Longjing for decades.

Tea-frying classes are compulsory for schoolchildren in his native Tongwu village.

Fan taught an elective course.

"Only two students enrolled. One was talented, but he decided against it as a trade. The greatest challenge is finding young apprentices."

He shows a photo of his hands, red and peeling from hours of kneading scalding leaves in metal basins.

"It's not fun," he says. "It's tough work." But it ensures quality.

"People's palates determine whether hand-processed Longjing is worth more," Fan says.

"It's easy to see if it is machine-processed, because it floats longer in the water."

Fan says he takes 500,000 yuan a year from the trade. He taught his 23-year-old son the skill and hopes it will become his career.

"My son is studying (tourism) at university, but he must produce tea. It's tradition. We need to pass it along. Still, young people have their own ideas."

They have made a pact. After university his son can do whatever he wishes for two years, returning only during the monthlong season to hand-process Longjing in spring.

"He then has to make a decision. If he can fry better than I do, he'll live better than I do."

erik_nilsson@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 08/26/2016 page9)