The forgotten cuisine

Updated: 2016-07-29 08:04

By Pauline D Loh(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

Editor's note: To understand China, sit down to eat. Food is the indestructible bond that holds the whole social fabric together and it is also one of the last strong visages of community and culture.

Traditionally, there are eight regional cuisines in China - Lu from Shandong province, Chuan from the Sichuan-Yunnan plateau, Yue or Cantonese, Min or that of the Fujian hinterland, Su from Jiangsu province, Zhe from Zhejiang province, Xiang from Hunan province and Hui from Anhui province.

Yet there is one more that not many acknowledge as Chinese, as it's recognized internationally as an independent cuisine - and it is a disappearing heritage.

Born of the Chinese diaspora, it is the food of immigrants to Southeast Asia. Known as Nonya or Peranakan cuisine, it is the cuisine closest to my heart and origins.

Peranakan, which means son of the soil in Malay, refers to third-generation immigrants who have adopted and adapted the food, language and customs of the land as their own, mainly in Singapore and Malaysia.

These descendants of early immigrants from China's southern provinces call themselves Babas and Nonyas, although they are also known as Straits Chinese. This term originated from the British Straits Settlements during colonial days, referring to the prosperous geographical trinity of Malacca, Penang and Singapore. These places were where Peranakans settled originally, and they are still where their descendants can be found today.

The first Chinese immigrants to Southeast Asia arrived as early as the 15th century, although some say it was even earlier.

The generally accepted story was that the first significant numbers landed in Malacca with Zheng He, the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) explorer, when the emperor gifted the Sultan of Malacca with a Chinese princess. Her descendants, and the offspring of her extensive entourage, became the first Chinese settlers.

As more intermarriage occurred, lifestyle changes began to reflect both cultures. Peranakan cooking is the best mirror of that cultural union.

Many of its dishes have unmistakable roots in Chinese cooking, although local herbs and spices give them an equally unmistakable identity. For example, a soy sauce-braised pork is reminiscent of a similar dish in Fujian, but the Peranakan version is spiced with toasted coriander seeds and whole dried chili pods.

Local herbs such as chili, turmeric, galangal, lemon grass, candle nuts, mint, pepper leaves and curry leaves are all part of the mise en place, and spices such as coriander, cloves, mace, nutmeg, cinnamon, fennel and cumin are all pantry basics.

Coconut in all forms is a common ingredient, whether used to thicken and enrich curries as a milk or grated to create a fragrant base in a stew.

The sour pulp of tamarind adds acidity to certain dishes, which is important in a warm climate, both to stimulate the appetite and to preserve the food in the days before refrigeration.

The local influence is there, too, such as in satay, those spicy aromatic meat skewers for which Southeast Asia is famous. Peranakans use pork for their satay, which would never happen with their Muslim neighbors.

Many Peranakan dishes are pork-based, with tripe, liver and kidneys all frugally used to make soup, liver rolls or stir-fries. Chicken and duck are also major meats. Comparatively, beef and lamb are not so frequently on the menu.

What makes these dishes stand out is that most make use of a basic herb and spice paste that must be freshly prepared every morning, the rempah. This spice paste uses chili, gingers, shallots and garlic in different proportions, but it is always slowly roasted in oil to create an intensely flavored, aromatic infusion that forms the base of curries, stews and stir-fries.

Peranakan cuisine is slow food at its best, and it subscribes to the principles of eating fresh, local and sustainable long before these buzzwords excited the chefs of today.

That's how the first Peranakan chefs adapted the cuisine of their motherland to the strange ingredients of their new kitchens. Often, the herbs and spices they used in the food would be growing just outside the kitchen door.

But evolution is relentless. As the pace of life quickens and the onslaught of convenience food runs parallel to material progress, Peranakan food is slowly losing its grip.

For many, it is too bothersome and laborious to prepare at home. With the family nucleus splitting up, the large army of Nonya mothers, aunts and sisters who can spend all day in the kitchen has disintegrated.

In Singapore, a good Peranakan meal is now more often enjoyed in a restaurant rather than at home. Somehow, it doesn't taste quite right anymore.

paulined@chinadaily.com.cn

Flavor profile of a classic Peranakan meal

Soup:

Itek Tim

This is a salted, mustard-green soup with duck and tomatoes, flavored with a dash of brandy and a few slices of tamarind fruit. It's an ideal appetizer, and there is no better way to stimulate the gastric juices than with a steaming bowl that is savory, salty and sour.

Sides:

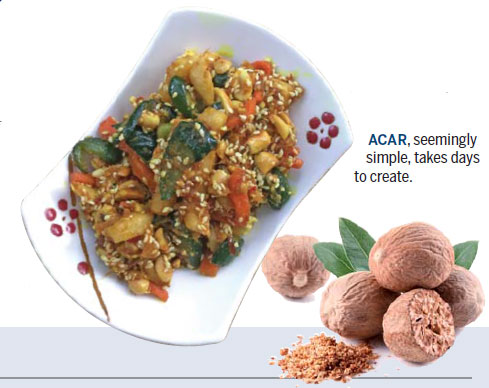

Acar

These pickles of crisp cucumber, carrot and jicama are smothered in a chili paste flavored with peanuts and shallots. The bright shade of yellow comes from pounded turmeric and other gingers. These seemingly simple pickles are a labor of love and may take days to create.

Brinjals with sambal

Brinjals, or purple aubergines, are cooked in lots of hot oil to keep the color and then smothered in a bright red, slow-cooked chili paste. These can be eaten hot or cold.

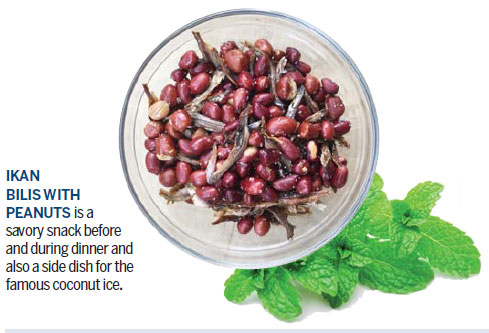

Ikan bilis with peanuts

Tiny whitebait are pan roasted to a crisp and dusted with salt and sugar. They are mixed with roasted peanuts to make a savory snack before and during dinner. This is also a side dish for the famous coconut rice, nasi lemak.

Sayur lodeh

Mixed vegetables cooked in coconut milk, flavored with lesser galangal and turmeric. The mixture may include cabbage, carrots, beans and the addition of triangles of deep-fried bean curd. It is often served with an onion and chili sambal paste.

Main courses:

Babi pongteh

This is pork hock braised in fermented soybean paste, similar to the soy-braised pork of Fujian province. The Peranakan version uses a sweet spice like toasted coriander and may add whole dried chili pods.

Hati babi bungkus

Pig liver is chopped, spiced and wrapped with pig's caul, the net of fat that surrounds a pig's stomach. Fried to a crisp, the cut rolls are dipped in a sweet, black soy sauce, sometimes scattered with fiery hot bird's-eye chili.

Chicken kapitan

The captain's chicken is a sour curry using tamarind juice to marinate the bird before cooking. Pungent, fermented shrimp paste or belacan adds a distinct kick to the dish. A relatively dry curry, it keeps well and was a festive season favorite because it needed no refrigeration.

Sambal kangkong

Pounded dried shrimps and a chili paste turn water morning glory or kangkong into a delicious, addictive vegetable. Masses of kangkong are washed thoroughly and rapidly stir-fried in a bean paste and shrimp paste rempah until just wilted.

(China Daily European Weekly 07/29/2016 page18)

Today's Top News

Obama, Merkel stress anti-terror cooperation

Downing Street cat fight: Larry vs Palmerston

No explosion, no injury report in Germany: Police

Geneva airport tightens security after French tipoff

Bill Clinton portrays Hillary as 'change-maker'

Priest, 84, killed in France, attack claimed by IS

Knife attacker in Japan kills 19 at disabled center

Michelle Obama rocks Democratic convention

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|