Choked by its own success

Updated: 2016-07-15 08:08

By Xu Lin(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||

Steps are being taken to restore Nanluoguxiang, a historic Beijing alley that was becoming an overcrowded, tacky tourist trap

When the pronouncement was made, it was akin to a doctor telling a patient he must give up drinking and smoking - and that if he is to survive, one of his legs will have to be amputated.

The patient in question is Nanluoguxiang, an area of Beijing that has grown fat on the attention and money of tourists over the past 10 years and now lies enfeebled, its arteries clogged.

|

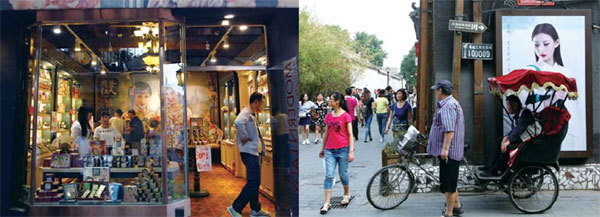

From Left: A cosmetics shop along Nanluoguxiang; a pedicab driver offers rides to tourists through the surrounding alleyways. Photos by Zhang Wei / China Daily |

|

The opening of a subway station at the end of 2012 brought more people to the narrow alleyway. |

Those arteries are the area's main alley, about 800 meters long, and the 16 alleys that run from it to either side, which once bustled with healthy activity and were the toast of the tourist industry.

In the heady days, which began about the time of the Beijing Olympics in 2008, tourists, most of them from overseas, flocked to Nanluoguxiang, which has a history dating back 700 years, to roam alleys with old courtyard houses, cafes, bars and creative shops.

The pronouncement in question came this April, when Dongcheng district said that Nanluoguxiang had voluntarily renounced its status as a national AAA-level scenic spot - an implicit admission that tourism had brought ills as well as benefits to the area.

It was announced that tour buses, often the lifeblood of tourism operations, would forthwith be banned, helping to reduce traffic and improving the lot of residents and historic buildings alike.

Nanluoguxiang is emblematic of many tourist sites around China whose promoters walk a fine line between raising awareness of local culture by showing it off to tourists and risking irreparable damage to that culture by dint of the huge numbers that flood in, changing the very nature of the place.

In the case of Nanluoguxiang, the place became so well known that Chinese joined their overseas counterparts in flooding in to enjoy it, leaving it overcrowded. Those numbers fed rampant commercialization and encouraged crass purveyors of goods common in myriad tourist spots throughout China.

On April 30, five days after Dongcheng announced the prescription to remedy Nanluoguxiang's ills, 70,000 tourists visited the area, about 23,000 fewer than had been there on the previous April 30. It offered a respite to harried local residents, who now do not have to worry as much about nosey tourists invading their privacy, wanting to know what courtyard houses look like.

However, for businesspeople, the changes have acted as a warning that they need to act decisively if the neighborhood is to thrive again.

"We would like Nanluoguxiang to be an interesting place that attracts lively people," says Xu Yan, president of the local chamber of commerce. "It's critical that we do something about the downmarket business operators such as snack dealers and make it a place full of innovation again."

Tourist groups now usually stay for only about 40 minutes and consume little, and though the new policies have done a lot to ease traffic congestion, they have had little impact on business, he says.

On May 17, the district government announced a three-year plan to better develop the considerable historic resources of Nanluoguxiang and set a target for more than 60 percent of establishments to have a cultural theme by the end of 2018.

The chamber is doing its bit with the government to give the area a new face and character by persuading businesses to smarten up their act. More than 80 stores were shut down temporarily or permanently in early June for licensing irregularities, the way they were running their businesses or the physical appearance of their shops, deemed to be unfit for the historic area.

When Xu opened his restaurant Taste in 2007, there were just 56 stores in the main thoroughfare. At one point this grew to as many as 250.

In 2009, the year after the Olympics, the area had attained worldwide acclaim, Time magazine ranked it among its 25 places for the best authentic Asian experience.

"New shops were springing up all over the place, and business was soaring, in terms of the number of visitors, sales and revenue," Xu says.

Inevitably though, rising demand for commercial space in the area led to soaring rents.

The average rent was about 2 yuan a day (30 US cents; 27 euro cents) per square meter, but these days it is more than dozens of times that, he says.

"When rents were low, you could do whatever you wanted without the slightest pressure. But as rents rose, people started to cut corners to make a fast buck, for example by selling snack food, and there were those who used low-grade ingredients.

"It was like bad money driving out good money, because some of the arts and crafts stores and bars closed, as they couldn't afford the rent."

Dominic Johnson-Hill, an Englishman who sold souvenir Beijing T-shirts, says people started selling cheap snacks such as kebabs and stinky tofu on the street from about 2010. The authorities have closed many of these unlicensed locations in recent years.

"That meant it turned from a creative street into a food street - unpleasant and noisy," Johnson-Hill says.

He had moved to Nanluoguxiang with his family in 2003, and in 2006 founded his Plastered 8 store.

The opening of a subway station at the end of 2012 proved to be another turning point, he says, drawing more people to the narrow alleyway and driving rents up even more.

Non-Chinese are attracted to secluded places, he says, and when they become more and more crowded, they go somewhere else. In fact, some of his regular customers started buying his T-shirts online because they did not want to jostle through crowds at Nanluoguxiang, he says.

Wang Haiyan, who with her husband opened a bar called Passby in 1999, says that before 2008 many of their customers were regulars, and many were lovers of literature and art. But now most are everyday tourists. In the early days, about 70 percent of customers were Europeans, but now only about 30 percent are non-Chinese, she says.

She hopes that as fewer people come, those who want to make easy money will be squeezed out of the market, rents will return to what she considers a reasonable level and creative types will be drawn back to the area.

"It's like restoring an ecosystem. It's anyone's guess about how long it will take, but I am confident things will come right if we do the right thing and persist with it."

Apart from tourists who may pay a quick visit, there are those keen on taking a look at the way of life in a traditional Beijing alleyway. A visitor who gave her name only as Wang says she is interested in architecture and rents a bicycle so she can tour Nanluoguxiang's ancient residences and chat with the locals.

More than 30 ancient residences of well-known people such as nobility and cabinet ministers, before and during the early 20th century, are well marked. Among them is the name of China's last empress, Wanrong, the empress consort of Puyi, the last emperor of China. Only three are open to visitors, the rest being mainly vacant.

Xu says there are plans to develop comprehensive tours that take in surrounding cultural sites in the alleys.

Liu Simin, vice-president of the tourism branch of the Chinese Society for Futures Studies, says it is inappropriate to develop a residential alley into a commercial street because it will gradually lose its essence - culture.

"Many well-known people used to live here. It represents Beijing's typical culture, and you can see the local residents' lifestyle. It is culture first and foremost that draws tourists here."

Liu acknowledges that early on what really attracted people to Nanluoguxiang were its cafes, bars and arts and crafts stores. Many of those who visited nearby Houhai gradually shifted their attention to Nanluoguxiang, and similar stores opened.

"Many Chinese prefer a blend of Chinese and Western because they want to enjoy the leisurely lifestyle the West offers. In one sense you can see that as creative, but you see it spreading all over the country."

The famous cafes along the Seine in Paris are scattered rather than squeezed into a narrow alley, he says, and Parisians are proud of their cafe culture and would not open a teahouse there just because many Chinese travelers visit the place.

xulin@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 07/15/2016 page19)

Today's Top News

Live: Truck attack kills over 80 in Nice

Li slams attack in France, expresses condolence

May stuns political world by appointing Boris Johnson

Li calls Sino-Mongolia ties 'best ever'

Russian, Chinese officials discuss space cooperation

25 killed, 50 injured as trains collide in Italy

EU called on to fulfill WTO promises

Ruling inherently biased and unjust 'piece of paper'

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|