School for thought

Updated: 2015-08-28 08:28

By Zhang Zhouxiang and Zhang Chunyan(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

BBC experiment triggers debate on UK and chinese education methods

Over the past three decades, China has witnessed extraordinary economic growth, which has generated interest across the world. Chinese education is considered one of the important factors behind that development.

With Chinese students often dominating international exams and education rankings, supporters say that the Chinese education system is world-class, producing respectful students who work hard in the face of fierce competition.

|

The five Chinese teachers featured in the BBC documentary, Are Our Kids Tough Enough? Chinese School. Provided to China Daily |

However, critics say the Chinese style of education is confined too strictly to absolute obedience. While Chinese students gain good exam scores, they don't always shine in scientific research as much as their Western peers, they say.

It has also been reported that China is introducing British-style elements into its education system because Chinese parents find it more creative.

A three-part BBC documentary, Are Our Kids Tough Enough? Chinese School, which was broadcast on Aug 4, 11 and 18, has reignited a heated debate across the globe, especially in China and Britain.

In the program, five Chinese teachers took responsibility for educating 50 students for four weeks at Bohunt School in Hampshire, southern England. Learning together in one classroom, the students, of mixed abilities, were put through a Chinese-style education system.

For four weeks, they wore typical Chinese school uniform and started the school day at 7 am. Once a week, there was a pledge to the two national flags. Lessons were focused on note-taking and repetition. Group exercises were undertaken, and students had to clean their own classrooms.

In the first two episodes, many teenagers found it difficult to adapt to the Chinese methods. The teachers were also not prepared for the stark differences between Chinese and British students. The teachers complained that classes were "chaotic".

After all kinds of ups and downs for Chinese teachers and British students, in tests at the end of the period, overall the students studying the Chinese method achieved marks about 10 percent higher in math and science compared with the rest of their year group, who continued to be taught by their regular teachers in the English manner.

Eventually some of the students accepted the Chinese style and reluctantly bid farewell to the Chinese teachers, even bursting into tears.

The program received high audience numbers. The first episode was watched by 1.8 million viewers, 8.6 percent of that night's total UK viewing audience.

It became a major topic on social media for over three weeks in both China and Britain.

Sam Bagnall, executive producer of the BBC documentary, says the program exceeded the producers' expectations as it triggered fierce debate on the different education systems among media and netizens.

According to the BBC: "This series was made to examine the significant differences between the Chinese and the British approaches to education. ... For several years some of the East Asian countries have beaten the UK on core subjects in international league tables, and we wanted to explore if their approach could be transferred to the UK classroom."

Discipline and hard work were the two main differences highlighted in the series.

According to a Twitter user: "British education has gone soft. Teachers are abused and students have no discipline. ... The public see it but the politicians don't." That comment received 5,693 "likes".

"I believe they (Chinese teachers) are right. The children are the products of three or four generations of people who have been supported by the welfare state in one form or another," another user says, receiving 3,116 "likes".

Some British people say the "Chinese school" doubled the time spent in class for only a 10-percent increase in results, emphasizing the importance of happiness and independent thinking to students.

However, Chu Yin, a Chinese citizen who is familiar with Chinese and Western education systems, writes in an article in Yanzhao Metropolis Daily, published in Hebei province, that the Western basic education system completes the process of social stratification unconsciously and gradually through the relaxed study progress.

"Western education looks very loose and happy, no pressures. Even some Chinese parents and children admire it," Chu writes, adding that Western children from rich families normally put more effort into study by going to private schools, something children from ordinary backgrounds can't do.

The Chinese education system gives people more opportunity to join the elite through discipline and hard work, Chu says.

Charles Law, an English teacher points out: "It's confusing to be told you are perfectly OK when the reality is that you need to improve to compete with your peers. Short term you might feel better. Long term you won't progress. It is far better to instil determination and perhaps set a long-term target (6 months) and make the necessary improvements."

Even with the huge differences that were shown in the program, many British netizens and viewers claim that the documentary reminded them of past school-days, as the discipline and some of the Chinese methods were present in the British education system decades ago, and still are at the private schools.

"That's not the 'traditional Chinese method'; it's the 'traditional method'. It's how I learned decades ago, and guess what? It worked. 'Discovery learning', or whatever you want to call it, hasn't reinvented the wheel," one netizen named Alfred Greengrass said during one British online debate, winning him 1,198 "likes".

Cat Smith, a British student, says in the UK's Open University online debate on the subject: "I think British students and state schools can learn a lot from the Chinese system." She added that her school has a lot in common with the Chinese system.

"In my experience, as I have attended many schools, it is the private schools that have these traditional rules in place to show respect to those above you and which have very set rules in place that do not tolerate any disrespect or behavioral problems," Smith says.

Joanna Dodd, director of a London-based PR group, has two adopted Chinese daughters both going to King's Rochester, an independent school in the south of England. The two girls, Wan Mae Dodd and Mei Dodd, are 13 and 10 respectively.

"Our school expects very good behavior: be on time for class; don't run in corridors, put your hand up to ask a question, hand your homework in on time, don't talk when the teacher is speaking to the class, mobile phones switched off during the school day," one sister says, citing the strict disciplinary requirements of the school.

"You can also get detention during or after school or may have to come in on a Saturday."

Besides comparing education systems in the two nations, more viewers, experts and teaching practitioners focused on the documentary itself, calling it a reality show and questioning the idea of reaching any conclusion from a simple one-month experiment.

The BBC took six months to select qualified Chinese teachers, Chinese media reported. The teachers had to have five years teaching experience in China covering English, mathematics, science or social sciences. They also had to be able to teach in English. And the five teachers were told by the BBC that they need to teach in a strict and very typical Chinese way.

But actually only Zou Hailian and Li Aiyun, two of the five, were recruited directly from the Chinese mainland, and the other three have lived in the UK for a long period. This led the audience to start asking: Are the teachers all using the current Chinese method?

Wang Xuming, a former spokesman for the Chinese Ministry of Education and now president of Language and Culture Press, says: "It (the BBC series) is an entertainment program, and the five teachers do not represent the majority of teachers in China.

"The five teachers are excellent in certain aspects, and their 'Chinese style', which includes penalties for disobedient students and harsh scolding for their faults, exists among some Chinese teachers, but definitely not all," he says, pointing out that some of details in the documentary, like the male teacher Zou scolding a student for "embarrassing the school", are no longer practiced by the majority of teachers in China.

He is echoed by Li Jun, associate professor of education policy at the University of Hong Kong, who says: "It must be noted that China is a huge country that does not lack diversity.

"The Chinese style in the documentary may be partly true in some cram schools for the key exam in China, the gaokao, the national college entrance exam, but not in most others," Li says. "No doubt that it (the program) is biased, incomplete and of course misleading."

Many Chinese netizens commented on China's Twitter-like platform, Sina Weibo, saying that although China's education is criticized for lacking independent and creative thinking, actually its basic education system is strong and has improved in recent years.

"The Chinese approach to education is not confined to absolute obedience, because teachers also encourage students' potential," says Zhang Qi, a 22-year-old student who has studied in China and Britain.

Some viewers rejected the premise that British schools should be labeled "without discipline", and didn't think the behavior of some of the students in the documentary was typical.

Iona Fleming, a British student, says in an online debate on the subject, that Bohunt students' behavior was not typical of British teenagers. "I would just like to say that not all British teenagers would behave this badly."

Some netizens point out that careful scrutiny revealed that all the students that acted disruptively in front of the cameras wore small microphones on their collars, while most others did not.

That aroused suspicion among viewers that the series might be more of an entertainment show instead of a serious documentary.

Jo Morgan, an experienced math teacher in the UK, says: "Education is not entertainment, and the editors were very manipulative."

For Christopher King, chairman of the Headmasters' Conference and principal of Leicester Grammar School, it was not a good idea to do the experiment without providing ample description or training in advance. In the UK, teachers and students usually exchange views in order to find the best way of education, he says in an interview with Chinese news websiteSina.com, adding that any teacher coming from overseas needs be given details about the system to make his or her teaching efficient.

King also says that Chinese teachers have a lot to teach UK students, but with the prerequisite that the two sides have ample communication and understand each other.

Dai Xiaowei, a Chinese producer who works for a TV station, says the BBC program uses a typical BBC style of narrative method. It pays attention to balance of the two sides, but what they want to compare is all shown and edited in this program.

The BBC's Bagnall says it was a formatted documentary in which they designed various scenarios, and the audience was aware of this. They then used documentary shots to record what happened. He says that the documentary is real and fully recorded.

Cameras were set up to capture the experiment and to "give a true representation of how the students reacted to the Chinese teaching style", the BBC adds in a statement.

Despite the various opinions and disputes on the program, some education experts note that the BBC documentary should be seen as an attempt to build a bridge between Eastern and Western-style education and an opportunity to start a broader discussion on different education systems. In particular, it should prompt people from both countries to ask what good education is all about, and what standards should be followed to determine the quality of education.

And one common point emerges: Cultural and country differences really matter, and the two countries can learn from each other's strong points to offset their own weaknesses.

Kathryn James, deputy general secretary of the UK National Association of Head Teachers, says: "It is always helpful for school leaders to learn from different systems, and the best teachers are continually questioning how best to teach their students.

Bohunt's Strowger says: "We took part in the program, and together with research we've done in Sweden, the Netherlands and the United States, as well as with a number of major companies, it provides fresh input on how we might improve the education we provide.

"The results of the program show that, when applied here in the UK, the Chinese approach to teaching can help the most academic students do well in tests," he says.

Chinese experts note that being exam-oriented is a serious flaw with the Chinese education system.

"Academic achievement has been used too often, too long and almost everywhere in reality as the only indicator for the evaluation of the performance of students, teachers and schools. But the real mission of education and schooling is of course much broader than this," says Li Jun with the University of Hong Kong.

"Chinese education used to have many soft components, such as diversity, individuality, morality, humanity and spirituality," Li says. "Chinese education should re-discover and re-embrace this soft heritage, and encourage innovative and alternative ways of teaching and learning."

Strowger adds: "An education is about so much more than only doing well in the exam hall. It is to create well-rounded individuals who can succeed in the classroom, in the world of work and throughout life."

Sun Jin, an associate professor of international and comparative education at Beijing Normal University, who is now a visiting scholar in Germany, says: "What China can learn from the UK and the West as a whole is to encourage its students to be more creative, independent and gain more social responsibility."

"The UK needs to promote the authority of teachers so as to make teaching more efficient and better exploit the potential of teachers," he says.

""China has long been learning from the West through various reforms and now a majority of its well-funded schools are adopting their ideas. The West, the UK included, is still arrogant and disdains using any idea from China. Actually both need to learn from each other."

Last year, at the launch of a China-UK exchange program for math teachers, Shen Yang, minister counselor at the Chinese embassy in London, said: "Through practical teaching and experience-sharing, teachers from both countries are trying to discover the differences between the two math education systems, raise standards and learn from each other."

David Thomas, who has worked as a head of math at a central London comprehensive school and as an adviser at the Department for Education, says: "Creativity is borne out of knowledge, not ignorance. Think of any great creative leap in any field. It will have been taken by a person with deep understanding of the traditions of their day - but who was able to challenge them in a meaningful way because of their knowledge. So it is because I want our children growing up able to challenge the status quo that I want to learn from Chinese teaching."

Contact the reporters at zhangzhouxiang@chinadaily.com.cn and zhangchunyan @chinadaily.com.cn

|

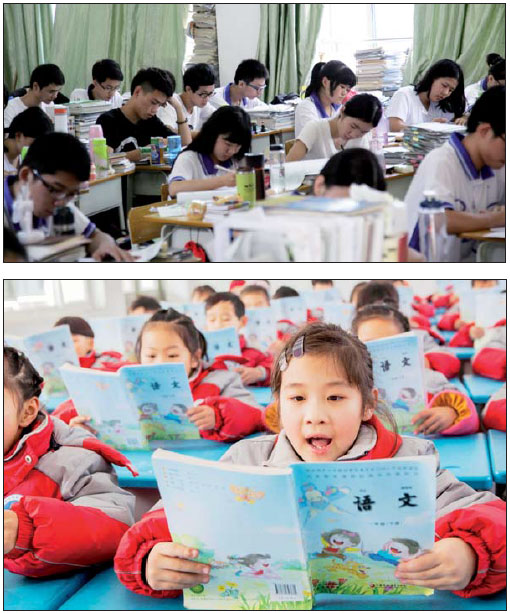

Top: Students prepare for gaokao, the national college entrance exam, in Guangdong province. Above: Primary students at class in Lianyungang, Jiangsu province. Photos provided to China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 08/28/2015 page1)

Today's Top News

Hungary scrambles to confront migrant influx

11 under investigation and 12 detained over Tianjin explosions

Up to 50 refugees found dead

in lorry in Austria

Net migration to UK hits record high

Suspect in Virginia TV shooting had history of workplace issues

Born in captivity, raised in freedom

Too hard to say goodbye to Tibet: China's Jane Goodall

Bank lowers lending rate to ease debts

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|