It's all smiles until you say it wrong

Updated: 2015-07-17 09:06

By Ginger Huang(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Dongbei dialect: The language of Chinese comedy, and just a little bit scary

Dongbeihua, apart from being the most common dialect in Northeast China, is the unofficial language of Chinese comedy.

For decades, comedians have used the dialect to rule the stage of the annual Spring Festival Gala, which airs at Chinese New Year, aided by the fact the dialect has a unique ability to make even the most mundane daily conversation sound comical.

Despite its effect, learning some Dongbeihua can help in everyday life, as a great many of its key elements have seeped into popular usage in the form of slang.

Before we get down to specific words and phrases, the first thing to remember when speaking Dongbeihua is to have the right attitude: Don't speak delicately. Anything resembling politeness, hesitation or gentleness will completely shatter the performance. The dialect is for the rash, warm-hearted and straightforward people of Dongbei. Be loud, intrusive, impolite and jovial. If not, your Dongbeihua just won't sound authentic.

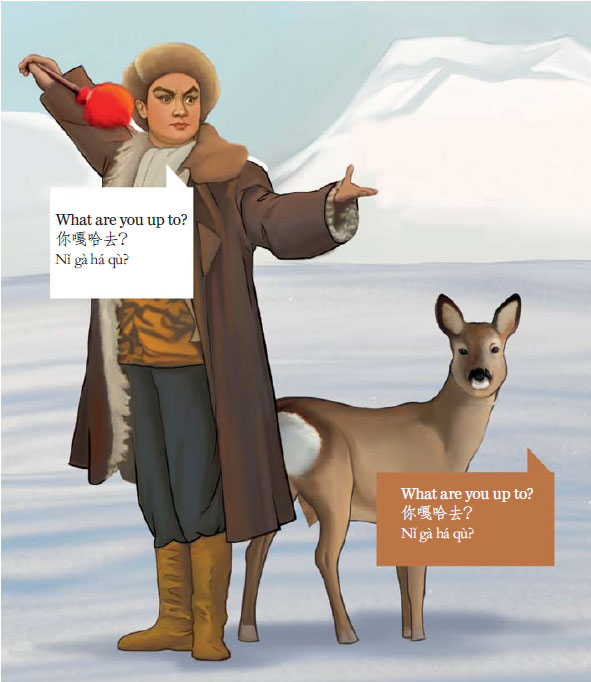

Now, the most basic greeting in Dongbeihua is:

What are you up to?

你嘎哈去?

Nǐ gà há qù?

Pronounce the vowels with your mouth by opening it unnecessarily wide - more so than when speaking Mandarin - and emphasize and prolong the há. To reply, simply throw the question back:

I'm not up to anything. What are you up to?

我不嘎哈。你嘎哈去?

Wǒ bù gà há. Nǐ gà há qù?

Another Dongbei phrase that has earned national popularity is the exclamation: "Oh, good heavens," or "哎呀妈呀," which translates as, "Ouch, mother." The standard Mandarin pronunciation is āiya māya, but in Dongbeihua the tones are similar to áiya máya. The emphasis is on the first character, ái.

Make sure the phrase bursts forth with great force because, ever straightforward, Dongbei folk are always genuinely surprised. Use it when you feel an ordinary exclamation just won't do.

Although Dongbeihua varies a little from province to province, there are some common rules you can follow. In some cases, the consonants zh, ch and sh in Mandarin are spoken as z, s and z, but in other places it is the opposite, so keep an ear out. The consonant r is invariably replaced with y. Here are two examples:

I'm from Dongbei.

我是东北人。

Wǒ sì Dōngběiyín, compared with the standard Mandarin's Wǒ shì Dōngběirén.

I want to eat meat.

我要吃肉。

Wǒ yào cī yòu, compared with Wǒ yào chī ròu.

In Dongbeihua, verbs often have a unique vividness. For example, to say "stay in" in Dongbeihua is "猫" or māo, as in to hide like a cat. So, you would say:

I'm not going anywhere for the holiday, just staying in.

放假我哪都不去,就猫家里。

Fàngjià wǒ nǎr dōu bù qù, jiù māo jiālǐ.

The most frequently used verb in Dongbeihua is undoubtedly 整 or zhěng. Its use is almost indefinable because it can be used in place of do, get or make, ballooning into an even wider range of meanings.

Get me two bottles of beer.

给我整两瓶啤酒。

Gěi wǒ zhěng liǎng píng píjiǔ.

You just don't understand what I'm talking about!

怎么跟你就是整不明白呢!

Zěnme gēn nǐ jiù shì zhěng bù míngbai ne!

Dongbei people seldom use an adjective without adding an adverb to intensify it. The most common adverb is 贼啦 or zéilā, which literally means stealthily smart. In Dongbeihua, you apply it before every suitable adjective for emphasis.

This restaurant is insanely good.

这馆子贼啦好吃。

Zhè guǎnzi zéilā hǎochī.

As well as being known for their warm-heartedness, Dongbei people are also famous for their pride and their short tempers. This point is best demonstrated if you type "Dongbeiren" into the Baidu search engine. The most searched items that automatically come up will be something like "Dongbeiren are all living Lei Feng" (东北人都是活雷锋, which refers to Lei Feng, the mid-20th century of selflessness) and "Dongbeiren picking fights" (东北人打架).

The Dongbei personality seems to perfectly embody both aspects, and it is no wonder Dongbeihua is rich in derogatory terms.

The most used derogative is show-off, 嘚瑟 or dèse, which means to squander money. It is used to chide someone for behaving vainly or irrationally, but only mildly and with an ironic tone. Sometimes it is simply used to tell someone to have a swell time or to indulge themselves.

You just got paid, and you have already squandered it all.

刚发的工资,没两天就被你嘚瑟光了。

Gāng fā de gōngzī, méi liǎngtiān jiù bèi nǐ dēse guāng le.

To say "cheat" or "dupe", use hūyou (忽悠). After Chinese comedian Zhao Benshan used it once during the Spring Festival Gala, the word became so popular that people are now not even aware of its Dongbei roots.

My grandma was duped by an insurance salesman.

我奶奶被一个卖保险的忽悠得团团转。

Wǒ nǎinai bèi yīgè mài bǎoxiǎn de hūyou tuán tuán zhuàn.

It is also used as a noun in the word dàhūyou (大忽悠), meaning a person who is a big cheater.

As for derogatory adjectives, there are a number of useful ones: To describe something shabby or ugly, use kēchen (磕碜); to say someone is stupid, use biāo (彪) or hǔ (虎); and to say something is dirty, use máitai (埋汰).

Your handwriting is really ugly.

你写的字太磕碜了吧。

Nǐ xiě de zì tài kēchen le ba.

You forgot your ID card when taking the train? You idiot!

坐火车忘了带身份证?你彪啊!

Zuò huǒchēwàng le dàishēn fèn zhèng? Nǐ biāo a!

This room is so dirty.

这屋子真埋汰。

Zhè wūzi zhēn máitai.

Last, but perhaps most important, if you are a first-timer to Dongbei, you need to learn to speak properly to avoid getting into trouble. It is said online that 60 percent of fights in Dongbei are started because someone did not respond properly to the bulky, tattooed, hot-blooded Dongbei man when he asked: "Why are you looking at me?" (你瞅啥?Nǐ chǒu shá?)

It is common sense that once asked this question in Dongbei, you have to be careful with your choice of words. It means the questioner is not only annoyed by your stare, but already considers it a challenge and is squaring himself up for a fight. If you remain oblivious of this and respond naturally with, "What's wrong with looking at you?" (Chǒu nǐ zǎdì? 瞅你咋地?), you might be in for trouble.

The next thing you might hear is: "Come on, buddy, let's have a good chat." (Guòlái, gēmenr, zánliǎ làolào. 过来,哥们儿,咱俩唠唠。) This is an official declaration of war.

Even if you err on the side of caution - "I'm not looking at anything, bro" (Gē, wǒ méi chǒu shá, 哥,我没瞅啥)" - things could end the same, as this too sounds like an insult to the Dongbei ear.

To stay safe, remember that Dongbeihua can be funny or scary. It is just a way to express yourself fully and with confidence.

There is a thin line between being funny and starting a fight in any language, as any class clown will tell you, but the Dongbei dialect has a lot to offer for the satirical and emotional among you, so give it a go, and remember not to stare at beefy Dongbei people.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily European Weekly 07/17/2015 page27)

Today's Top News

China, World Bank pledge $50m for poor

Industries should be on digital Silk Road to expand market

'Occupy Central' leaders to stand trial

Europe moves to restore funding to Greece after bailout vote

MH17 final report to be published in October

ECB raises Greek bank funding as Europe backs new loan

Greek parliament approves debt deal and reforms

British boy with eczema wins support from Chinese Internet users

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|