Where oceans, mountains and honey meet

Updated: 2015-05-15 08:46

By Riazat Butt(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

British author tells the story of the resilient China-Pakistan friendship

Yellow Crane Tower in Wuhan, Hebei province, is one of the most famous towers in China. Its design and picturesque scenery is a magnet for tourists, and its history and symbolism have inspired famous Chinese poets including Li Bai (AD 701-762), who wrote verses when he bade farewell to his friend and colleague Meng Haoran.

The distinctive building, together with Li's verses, have left a lasting impression on British author Andrew Small, who visited Yellow Crane Tower in 1998 and recited the poem, in full, upon seeing it.

|

British author Andrew Small's first book, The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia's New Geopolitics, analyses the resilient friendship between the two countries. Wang Jing / China Daily |

"I was an English teacher at the Civil Aviation Academy in Guangzhou and the students were from all over China. I was given poems I should recite when I went to their favorite spot in their hometown. My Chinese was a lot better back then; it's OK now."

He then proceeds to declaim Li's verses in Chinese, from memory, amid the well-watered gardens of the Shangri-La Hotel in Beijing:

"Gu ren xi ci / Huang He Lou,

yan hua san yue / xia Yangzhou.

gu fan yuan ying / bi kong jin,

wei jian Changjiang / tian ji liu."

The translation:

My old friend's said goodbye to the west, here at Yellow Crane Tower. In the third month's cloud of willow blossoms, he's going down to Yangzhou. The lonely sail is a distant shadow, on the edge of a blue emptiness. All I see is the Yangtze River flow to the far horizon.

He says: "You do the walk with your hands behind your back, your head bowed; you go to these spots and recite these poems. Given how China looks now, the ability to recall the China of a different age is quite nice."

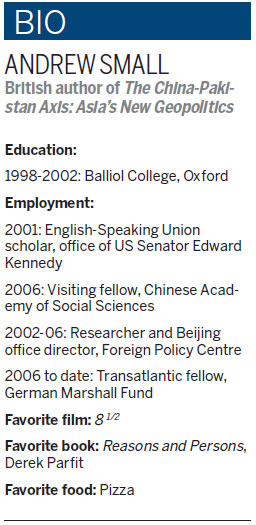

His first visit to China, 17 years ago, was the beginning of an enduring fascination with the Middle Kingdom. Small is now a transatlantic fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States and specializes in China's relationship with the United States, the European Union and its policy in South and Southwest Asia.

His first book, The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia's New Geopolitics, was published this year and pores over the resilient friendship between the two countries. The book's timing is fortuitous. President Xi Jinping visited Pakistan in April and announced a $46 billion (41 billion euros) investment program as part of China's One Belt, One Road initiative, which will tie the country closer together with other countries in Asia, as well as East Africa, the Middle East and Europe.

"It was very difficult to write this book," Small says. "Nobody had written anything serious about the China-Pakistan relationship for a long time, not since the 1970s."

"After university I started working on China foreign policy issues when I was working at the Foreign Policy Centre," he says of the London think tank. "I wasn't originally working on China, but it was when China started taking off as a global power."

China and Iran are the two countries that have most absorbed him over the years. Their culture, history, literature and politics intrigue him. He needed exposure and engagement with a country in order to understand it.

"Guangzhou at the time was chaotic, a bit of a mess of a city. Shanghai and Beijing had all the money and Guangzhou was a mad, unplanned sort of place. It took some getting used to, but I became rather fond of it. You can eat the best food in Guangzhou than anywhere else in China. That's still the case."

There was a sense of China being a growing power when he was first in the country, he says. On returning in 2003, to live and work in Beijing, that feeling was at its peak.

"China had been in the World Trade Organization for a few years. GDP had crossed a certain threshold. Everyone was in this massive process of adjustment, both internally and externally. The expat community was relatively small. Previously people came for cultural or political reasons. Then people saw the future and wanted to know how China was going to change the world."

Pakistan entered the frame when, in 2008, US President Barack Obama came to power. There was a push on the US side, Small says, to make Afghanistan and Pakistan the focal point for the US-China relationship. There were those in Washington who thought Pakistan was an area where China and the US should share interests.

"There had previously been cooperation, in the 70s and 80s. It was almost like, 'Can we get the old gang back together?'" And then Small realized that there was little written on the China-Pakistan relationship.

"There were so many myths and false rumors, and part of the effort was to disentangle these. For instance, are there really 10,000 Chinese soldiers in northern Pakistan? No. It was difficult, more so than any other area I had worked on. It's a very close relationship; it's a very protected relationship. Pakistan was the case where they (China) were the most cautious. Lots of areas are sensitive, and that's why nobody had been able to write about it, so there was a lot of note comparing and flitting between the US, India, China and Pakistan.

"In Pakistan this kind of information is not publicly available so I had to have extended visits. I had to travel around more than I did in China because here I already had networks and contacts. I was coming out to China five times a year."

The book has received positive reviews in the US and Pakistan, although Small concedes that the threshold for non-hostile books about the South Asian state is very low. "I've not had the chance to test the book out on people in China but being paired with China is very helpful, full stop. This parallel, important relationship, having it laid out, is very advantageous, even if you point out some of the tensions."

China is spending a vast amount of money in Pakistan, more than twice the amount of all foreign direct investment Pakistan has received since 2008, and more than the US, its largest donor, has given since 2002. It is 18 percent of Pakistan's GDP and is greater than the GDP of more than 100 countries. Pakistani officials say that some projects will be completed in a few years, and others could take up to 15 years.

The investment targets the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and combines energy and transport projects. It begins in Gwadar, in southwest Pakistan, and ends in Kashgar, in China's Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. The building programs could create tens of thousands of jobs in both countries, as well as inject life into Pakistan's erratic economy. Better road and rail connections also mean easier trade routes for China.

Xi, who had never visited Pakistan before last month, said in an article published before he arrived in Islamabad: "I feel as if I am going to visit the home of my own brother." He also said the two nations' friendship was "higher than mountains, deeper than oceans and sweeter than honey".

Of the $46 billion investment program, Small says: "There is a lot riding on these projects. This is the frontline of One Belt, One Road. There is a strategic reason to do it; there is a domestic imperative. It has been the Pakistanis pushing for this (investment), but the Chinese want to do this. There is a lot that can happen on the Pakistani side - militancy, corruption and politics - but even then there is an ability to do the mega projects. The things they (China) want to make happen have happened."

riazat@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 05/15/2015 page32)

Today's Top News

Xi to give Modi a hometown welcome

Li invites Cameron to visit China

Putin, Kerry pledge to get ties back on track

China set to delay maiden flight of C919 commercial jet

Ten panda poachers caught in Southwest China

Beijing concerned by Pentagon plan

Xi's trip highlights China's resolve to safeguard peace

China, Russia start search for remains of Soviet Union soldiers

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|