The heroes time forgot

Updated: 2015-05-15 08:39

By Joseph Catanzaro, Zhou Wa and Liu Xiaoli(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

As the world marks the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, Chinese valor in a tragedy at sea is recalled

Shen A'gui stares vacantly up at the ceiling above his bed, hands fluttering weakly like broken birds on the bunched up blankets.

They are the hands of a fisherman, each scar and callous a footnote for a life spent hauling oars and nets in the stony seas off China's southeast coast. They are the hands of a man who saved lives at a time when the world was gripped by war and so many others were taking them.

Standing at the bedside, Shen's friend Xu Guoquan, 67, shakes his head.

"He's 92 years old and he's sick with a fever," Xu says.

"He hasn't spoken in two weeks."

The old fisherman has been many things in his long life. He is a father with grown children; he is a grandfather; he was a husband; and now he is a widower.

He is also the last living link to an incredible act of selfless courage, the only surviving Chinese participant of a daring rescue in which hundreds of British servicemen were saved from almost certain death in 1942.

"I don't know if he remembers," Xu says. "He is the last."

Suddenly, a paper-thin voice rustles in the cupboard-sized apartment where Shen's sickbed rests on the concrete floor.

"I was scared," Shen whispers. "I was only 19. The Japanese were shooting. Hou'ao beach that is where we rescued the foreigners."

Shen's voice and memory unlimber. He has not forgotten the day when the war came to his home on the Dongji Islands, and a humble group of Chinese fishermen became heroes.

As the world this year commemorates the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II, China is preparing to mark the conclusion of what it calls the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression.

A bloody chapter in the wider conflict that engulfed the world, Western and Chinese historians have only recently begun to shine a light on how China's fight against imperial Japan played a crucial role in the greater Allied victory.

Professor Rana Mitter, director of Oxford University China Centre and author of the book China's War with Japan 1937-45: The Struggle for Survival is among those working to broaden the historical narrative.

During the Cold War, Western nations and China both forgot the significance of their wartime alliance against Japan, he says.

"Various things that China did changed the path of the war," Mitter says. "Most noticeably the decision to continue resistance after (Japan invaded China in) 1937, when they could well have surrendered and done a deal with the Japanese. Over the course of the war, at their height they (China) were holding down 500,000 Japanese on the Chinese mainland."

Those Japanese troops, tied down fighting Chinese soldiers, could not be deployed in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Theater, a handicap that may well have changed the outcome of key battles.

China's resistance also prevented Japan from pushing into new fronts that could have had a significant impact on the war in Europe, Mitter says.

A Japanese incursion into British India would have threatened a source of manpower and resources vital to the fight against Nazi Germany. A push into Russia, an ally that proved crucial in Adolf Hitler's eventual defeat, would have seen the already beleaguered Soviet Red Army fighting on two fronts.

Mitter says Japan planned to conquer China in three months. Almost five years after the initial invasion, when Pearl Harbor was bombed, Japan was still "stuck in the Chinese quagmire".

But China paid a heavy price for its refusal to surrender. By the time the guns finally fell silent in 1945, an estimated 15 million Chinese soldiers and civilians had been killed, according to Mitter. To put this slaughter into context, the fighting in China is estimated to have accounted for 90 percent of all casualties in the Pacific Theater.

"These were major contributions that don't tend to be remembered very much in the West," Mitter says.

Conversely, Mitter says, China was only able to stay in the fight because of the supplies and support it received from its Western allies, in particular Great Britain and the United States, which were also engaging Japanese troops elsewhere who could have been thrown against China.

"Without the Chinese contribution, it's much harder to see an Allied victory in Asia during the war," he says. "But without the British and American contribution, it's also much harder to see a Chinese victory."

Even less well known are the human tales of camaraderie and common cause between locals and foreigners in China during the war.

In Shenyang in the country's northeast, Chinese locals suffered and endured alongside captured British, American and Australian troops in the concentration camps. In Guizhou, in China's southwest, foreign doctors working for the Red Cross helped save the lives of many thousands of Chinese soldiers and civilians.

In the western, central and southern provinces, British and Australian commandos trained and fought side by side with Chinese guerrilla forces on clandestine missions. During the infamous Burma campaigns, Chinese soldiers marched in lockstep with other Allied contingents in the battle against the Japanese war machine. And in various locations across war-torn China, where the bootheel of imperial Japanese occupation rested heavy, locals like Shen staged a number of daring rescues and breakouts in an effort to save foreign prisoners of war.

"This is really a story about both sides helping each other, and I hope that's the view that becomes more lodged in the historical consciousness," Mitter says.

They may be the forgotten allies on the forgotten front, but seven decades on, there are those in China who still remember.

On the docks of Qingbang Island, one of four wave-battered rocks that make up the Dongji Island chain, Liang Yijuan walks slowly among the fishmongers and women mending nets.

The 86-year-old retired fisherman has a face cured by decades of salt spray and hard weather. It crinkles when he smiles. He pauses by the water's edge and stares out at the sea.

One October morning when Liang was 13 years old, he stood on this same spot and scanned the horizon for any sign of his parents. They and another 196 locals in 46 sampan boats had hurriedly cast off from the docks early in the day, called out to sea by a noise like thunder and a rising column of smoke.

It was Oct 1, 1942, and the Japanese transport ship Lisbon Maru had just been torpedoed by a US submarine about three nautical miles off the coast of Qingbang.

Unknown to the Americans aboard the USS Grouper, in addition to 700 Japanese troops, below decks the holds of the Lisbon Maru were crammed with almost 2,000 British servicemen taken prisoner after the fall of Hong Kong. As the ship sank, the ranking Japanese officer gave the order to secure the hatches and leave the captives to their fate.

The POWs who managed to break out were met with deadly machine-gun fire.

Shen and Liang's parents were part of the rag-tag Chinese fishing fleet that arrived at the scene.

Despite being fired upon initially by the Japanese, the fishermen decided to risk all to save the foreigners.

Eventually, almost 400 British soldiers were rescued from the sea and Japanese gunfire.

Dr Tony Banham is the author of the book The Sinking of the Lisbon Maru: Britain's Forgotten Wartime Tragedy. The British death toll would have been much higher if the Chinese fishermen had not placed themselves in danger to pull off the rescue, he says.

"In many cases, the fishermen pulled the British from the water right under the noses of the Japanese. They could have been shot. Some survivors believe the Japanese only joined in the rescue efforts because they saw what the Chinese had done and realized that some of the prisoners would now survive (to tell the tale)."

Liang remembers the moment his parent's fishing boat tied up at the docks carrying a load of emaciated British soldiers.

"It was a bit strange," he says. "I had never seen a foreigner before."

Despite having very little, each fishing family took a few of the escaped POWs into their homes, fed them and in some cases clothed them.

But Liang says the certainty that the Japanese would return hung ominously over the islands.

When three of the British soldiers indicated they wanted to hide, it was 13-year-old Liang who helped them, taking them up into the jungle to a cave that in the old times had been used as a shelter for children during pirate raids.

"I used to play in that cave, and I suggested we hide the soldiers there," he remembers.

It was lucky he did, he says, because the next day the Japanese returned in force.

Liang smiles an old man's smile at the memory of a young man's bravado.

"I wasn't afraid," he says.

He now realizes he should have been.

A few thousand kilometers away from where Liang's home clings to the cliffs on Qingbang, Tang Qiude, 57, burns paper and incense in front of a tomb outside the village of Lao'ou, a backwater township on the southern Chinese island of Hainan.

Every year on Tomb Sweeping Day, the festival when Chinese people honor their dead, Tang carefully places offerings of wine and food at the gravesite near his farm and lets off strings of firecrackers to scare away evil spirits. He has done this for the past 20 years, taking over the ritual when his father died.

It is the traditional Chinese way of caring for ancestors, but the men buried here are not Chinese, and they are not blood relations.

The tomb bears the English inscription "Lest we forget".

It is the final resting place of two soldiers from the Australian Gull Force contingent.

"My son and my grandchildren will do the same and take care of them one day," Tang says.

For the farmer, it is a debt of honor that must be paid.

Locals say the Australians were among a group of men who escaped from the nearby Basuo POW camp. Once free, they chose to fight side by side with the Chinese resistance.

Fu Tianxiang, now 82, remembers meeting the Australians in 1943 when he was 8 years old.

"I was so curious about foreigners, so when I heard that there were two of them in our village I rushed to see them," he says.

"They were in bad shape."

"The Japanese came here frequently to search for the escaped Australian POWs and threatened to kill all the villagers if anyone tried to hide them. Everyone kept the secret."

"They lived here until they died of disease."

Dr Karl James, a senior historian at the Australian War Memorial, says China remains the "unappreciated fourth ally" of World War II, and much of its contribution has been overlooked, a fate shared by Allied forces deployed on the Chinese front.

Among the ranks of the forgotten is British Military Mission 204.

In the mission, made up of a number of contingents that secretly trekked into China via the Burma Road from 1942 onward, about 180 British and Australian commandos were deployed to western and central China to train local troops in guerilla fighting tactics.

"They were called the Surprising Battalion," James says of the Allies' Chinese counterparts.

But it was an uneasy alliance.

"There were problems with communication, language and cultural awareness," James says.

The bulk of Allied troops in China between 1944 and 1945 were a force of 27,000 US troops, nearly 18,000 of them from the US Army Air Forces. Mitter says there were culture clashes.

"There is camaraderie, but I wouldn't want to say it's an uncomplicated story of everyone simply mucking in together: There are tensions as well during that time."

But on the island of Qingbang in 1942, Liang says the solidarity ran both ways.

Knowing that to do anything else would risk the lives of the fishermen and their families, all but the three British escapees Liang had hidden surrendered themselves to the Japanese.

"The Japanese came many times looking for the (three hidden) soldiers," Liang remembers. "They captured some villagers and pointed guns at their heads and asked where the UK soldiers were hiding. No one told them anything. When the Japanese left I went to the cave and told the British soldiers it was safe. When they came to our house they started crying. One of them sat me on his lap. I think he was trying to tell me he was thankful. He gave me the thumbs up."

The servicemen left Liang a harmonica as a gift, but his family was so poor he had to sell it to buy a bag of rice.

Passed between guerrilla fighting groups, the three POWs were smuggled across China to British forces operating in the country's west. They were repatriated to the UK.

On the biggest of the Dongji Island chain, Miaozi, Liang's daughter Liang Yindi, 48, is one of several locals who take care of a small museum dedicated to the sinking of the Lisbon Maru. Visitors are few and far between, but she sweeps the floors and dusts diligently, all the same.

"It is important for people to remember there is a link between the people here and the UK, for people to know that 70 years ago there were Chinese fishermen who were brave and warm hearted," she says.

Ten years ago though, she says, the island did receive some visitors. It was a small group of elderly British veterans who had survived the sinking of the Lisbon Maru.

To this day Liang is unsure, but he thinks one of the old men was among the three he helped save.

"We hugged and we cried," he says. "I had never forgotten them. I will always remember those nice men."

Banham says he only knows of one British veteran from the sinking who is still alive today. Similarly, Shen is believed to be the last of their rescuers.

Lying in his sickbed 70 years on, Shen says he never expected or wanted accolades for doing the right thing. He too met with one of the returning veterans in 2005. The embrace they shared was reward enough.

"It is better to save one life than to build a temple to the gods," he says.

Contact the writers through josephcatanzaro@chinadaily.com.cn

|

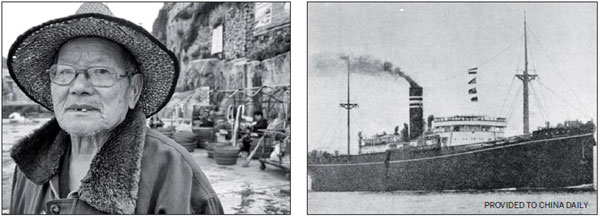

Shen A'gui, 92, who is believed to be the last living fishermen to have participated in the Lisbon Maru rescue, at his home in Zhoushan, Zhejiang province. Photos by Joseph Catanzaro / China Daily |

|

Left: Liang Yijuan, 86, on the docks of Qingbang Island. He was a boy when he hid British POWs in a cave. Right: The Lisbon Maru, which sank off the coast of Qingbang Island after it was torpedoed by a US submarine on Oct 1, 1942. |

|

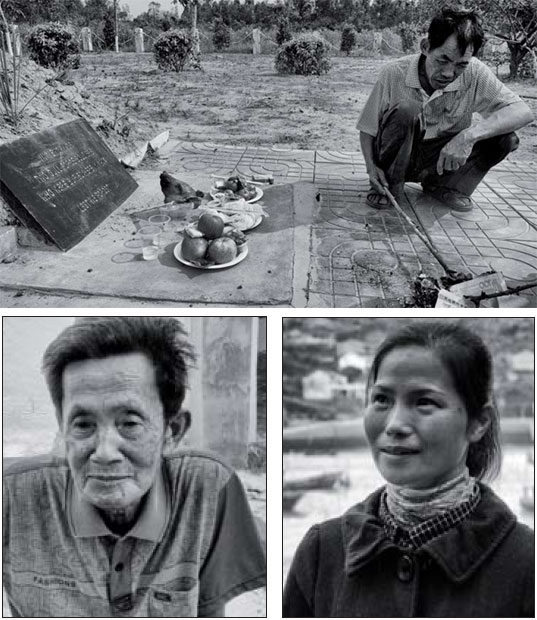

Clockwise from top: Tang Qiude sweeps the Australians' tomb; Liang Yindi, 48, takes care of a small museum dedicated to the sinking of the Lisbon Maru; and Fu Tianxiang, a villager in Lao'ou, who witnessed Australian soldiers at the village seven decades ago. Photos by Liu Xiaoli and Joseph Catanzaro / China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 05/15/2015 page1)

Today's Top News

Xi to give Modi a hometown welcome

Li invites Cameron to visit China

Putin, Kerry pledge to get ties back on track

China set to delay maiden flight of C919 commercial jet

Ten panda poachers caught in Southwest China

Beijing concerned by Pentagon plan

Xi's trip highlights China's resolve to safeguard peace

China, Russia start search for remains of Soviet Union soldiers

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|