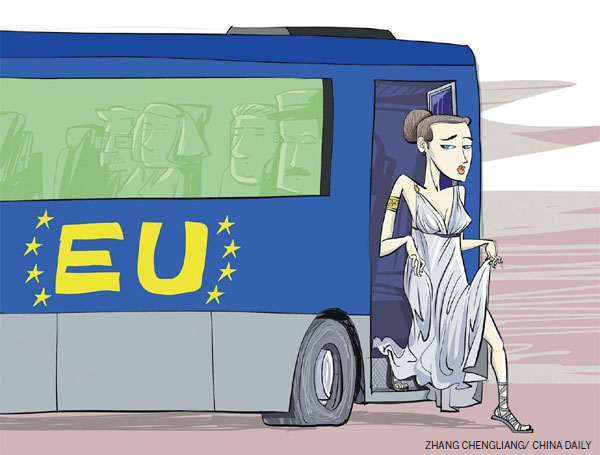

For the EU, the endgame is nigh

Updated: 2015-03-27 07:29

By Giles Chance(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Greece may be forced to leave the euro and return to the drachma after a large devaluation

As China has grown, its economic and geopolitical perspective has become global. Today, Europe is vitally important to China. The richer western European countries are major customers for Chinese exporters, and Europe as a whole and the United States are the major markets for Chinese goods. China holds a substantial portion of its large foreign reserves in debt issued by European countries. Since 2009, China has invested heavily in Greek infrastructure. Recently, China has started to initiate a new Silk Road that would provide a Chinese entry point into European markets from the southeast, through Greece and Belgrade, supplementing its free trade agreement with Switzerland and its container shipments through the Dutch port of Rotterdam.

But while the US recovers, the European crisis continues. The collapse of the euro, seemingly impossible a few years ago, is no longer unthinkable. Syriza's victory in the Greek elections in January brought the despair of Europe's large economic underclass into the elegant, richly furnished council chambers of Brussels and Frankfurt, from where Europe is governed. You can print money by pressing a button on a computer, but no one has invented a computer game that banishes poverty and unemployment. Since 2011, the European Central Bank has done what it takes to keep the euro system together. But the European central bank can only buy time for Europe's politicians to establish mechanisms that strengthen the euro's fundamentals. There is a limit to what a Central Bank, even one led by a governor as farsighted and decisive as Mario Draghi, can do.

Sadly, the time he has bought for fundamental economic restructuring has been largely wasted. The political standoff between Greece and the European Union, led by Germany, is stealing headlines and taking attention away from the key underlying issue. This is that economic failure is creating desperation, which is destroying Europe's social fabric and cohesion. In Spain, the extremist party Podemos, which was set up less than 15 months ago, is leading the national polls and could win the country's next election, to be held this year. In France, which finds itself unable to introduce unpopular but essential fundamental reforms, an election held today would probably be won by the right-wing extremist party led by the charismatic Marie le Pen. In most parts of Europe, the spirit of cooperation and progress that has supported the ideal of European economic and political integration since 1945 is being undermined by economic and social decline.

Part of the problem derives from the financial crash of 2008 and the response to it. The problems caused by the crash only started to show up in Europe in 2009 and 2010, as economic recession cut national income from taxation, and European banks were eventually forced to admit their losses. Sticking plaster was applied to the wound, stemming the flow of blood, but failing to address the underlying problems. Slowly, European banks wrote off some of their losses and raised new capital, while the European Central Bank provided a cushion of cheap money that could provide only temporary relief. Cheap money brought ultra-low interest rates, lifting the value of real estate, stocks and other assets. The asset-owning wealthy benefit. But the suffering of the young, unemployed and the struggling middle-class majority, who own few assets, increases. Greater social inequality and a sense of unfairness are felt by many Europeans, including young people who have never had a full-time job, workers on low incomes, and people who lost their jobs during the recession and are still unemployed. These people are the natural supporters of political movements such as Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece that promise fundamental change in the established order. One has only to study Europe's history of the past century to recognize familiar symptoms of social dislocation that led earlier to extremism and eventually to war.

The problem for the euro also derives from the fact that the EU is not a full union. The European countries in the union and in the euro currency system have not made a permanent transfer of national sovereignty to Brussels at the center, although they have given up control over their money supplies and interest rates as well as much of their legal systems. When things are good, everyone supports the idea of monetary and social union, but when the economic weather turns nasty, each country worries about its own problems, and independence from the European straitjacket may become an attractive exit route. The United Kingdom, which belongs to the EU but not the euro currency union, has been promised a referendum on continued EU membership by its Prime Minister David Cameron. This is a way for him to put off the fundamental split over Europe within his own party, the Conservatives, until after the next British election in May. If Cameron remains prime minister, and probably even if he does not, the British will get their vote on membership of the EU, and they may vote to leave it.

What about Greece? Here, the impoverished majority has made a bet that Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, will be forced to give way to Greek demands for debt forgiveness in order to preserve the euro system. They have probably miscalculated, because Merkel's unassailable position within Germany rests on her ability to appear as conservative as most Germans, while at the same time often pursuing liberal and adventurous policies. Merkel knows that Germans feel deeply that they have contributed enough to Greece, and that they are not in the mood to change loan agreements that were approved by the Greek Parliament. Syriza's effort to renegotiate by holding a gun to the head of the EU will probably fail. If it does, then Greece, which cannot raise money on the capital markets without external support, will be forced to leave the euro and return to the drachma after a large devaluation. The Greek banking system will immediately become insolvent, and the country will collapse into a financial and economic crisis that will make its current problems appear as nothing.

But even if Greece succeeds, against the odds, in agreeing on terms with Germany and the rest of the EU, the European system as it now stands is doomed, because the lives of people in many European countries are getting worse. Within the euro, only the Netherlands can match German efficiency and productivity. In a fixed currency system with only one interest rate, this means for most euro countries that the currency becomes increasingly overvalued, their economies become increasingly uncompetitive and poverty and unemployment spread wider. We are seeing the first signs that growing social strains that follow from economic failure will break up at least part of the euro system.

Europe's crisis is an opportunity for China, whose deep pockets will allow it to carry the losses it would suffer from a Greek exit from the euro. China could also benefit from closer partnerships with European countries like Greece that find it an important partner in their moment of need.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily European Weekly 03/27/2015 page10)

Today's Top News

Voice recordings show one pilot locked out cockpit

Geely to invest $372m on new London Taxi facility

Netherlands' PM to meet with Xi

Italian vineyards see a glass that's half full in China

Moscow says US security strategy 'anti-Russia'

Cockpit voice recorder of crashed airliner found, probe under way

Queen approves new coin for birth of second baby of Prince William

House passes resolution urging Obama to send arms to Ukraine

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|