China in a box, music included

Updated: 2015-03-13 08:12

By Jessica Rapp(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

How combining Swiss and Chinese culture gives you something not far removed from an expensive iPhone

"In Switzerland they had brotherly love, they had 500 years of democracy and peace, and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock." So says Harry Lime in the film The Third Man. Alongside the famous cuckoo clock, he might easily have added the Swiss music box.

When Ningyi Zhang, an antique dealer in Beijing, began hauling Swiss music boxes to China he suspected there would be no shortage of interest. After all, these ornate furniture-sized instruments were great conversation pieces. Their delicate melodies and elaborate construction attract wealthy collectors eager for foreign items and to join the nation's nouveaux riches.

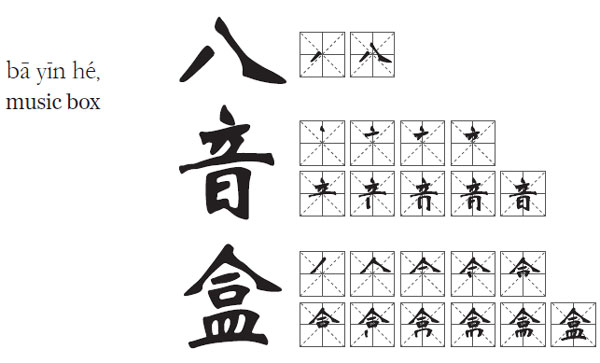

Zhang, despite little to no experience in musicology, was rightly convinced China's luxury consumers were ready for the music box (八音盒 bā yīn hé, or eight note box, named after the octatonic scale common in Western music as opposed to China's pentatonic scale). He acquired more than 70 within a few years.

"People are really charmed that these music boxes work without electricity in a world where everything is electronic," Zhang says. "People are very attracted to things that work with gears, springs and levers. This is something purely mechanical that can also store great music."

Zhang's music boxes are decorated with etched wood and dancing porcelain figurines, and some are even coin-operated. In 19th century Europe, train stations, pharmacies and amusement parks would all have had one, generating revenue thanks to passersby who fancied jamming to polkas and waltzes. Zhang's music boxes had all the fashionable tunes, manifested through the mechanical plucking of violins, the ringing of bells and the beat of small drums.

There is one that plays the Chinese folk song Mo Li Hua (茉莉花), or Jasmine Flower. Watch CCTV's English channel for about an hour and you will probably hear it somewhere. This is where the story gets very interesting. Once Zhang thought he knew all there was to know about 19th century Swiss artisan manufacturing culture, he acquired a Chinese-themed music box that was auctioned about the same time The New York Times published an article that cast light on its fascinating history.

Zhang knew this much: Chinese-themed music boxes were made in small quantities in the Jura Valley of Switzerland toward the end of the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) for export to a few Chinese aristocrats. Interest in music boxes from that time followed an obsession with mechanical objects, namely elaborate watches and clocks, which had been a feature of the Qing era. Emperor Qianlong (乾隆皇帝) notoriously had one of the largest clock collections in the world, many still on display in the Forbidden City in Beijing today. These luxurious time pieces, often gilded and set with gemstones, were given to imperial families or traded for porcelain and tea. However, little is known about who, specifically, owned these music boxes.

They were customized for China in almost every aspect, much in the same way Apple has marketed a gold version of its iPhone 5s specifically for wealthy Chinese consumers. No waltzes or polkas this time. Instead, Chinese listeners were granted a number of their own folk songs collected by Frederic "Fritz" Bovet, a member of a Swiss watch-making family, on his travels throughout Asia during the mid-1800s. Bovet recorded 10 melodies in China, which included Mo Li Hua and Shi Ba Mo (十八摸), also known as Eighteen Touches or Erotic Massage, a bawdy brothel song that was banned in China along with brothels.

"Shi Ba Mo is a bit of a naughty song, and one has to wonder where the Swiss musicologist collected his tunes," Zhang jokes. But regardless of Bovet's personal wanderings, these songs in their form and their significance could have been lost if they were not documented in the music box, and for a person who eventually came to possess the music boxes. And, no, it was not a Chinese aristocrat.

The New York Times article, penned by American music history professor W. Anthony Sheppard, revealed to Zhang what makes the music box so valuable. Fast forward to the early 1900s, and Zhang's music box was, Sheppard suggests, sitting in the home of Italian baron Eduardo Fassini-Camossi. Sheppard tells us that the baron, an amateur composer, had probably picked up the music box at a "loot auction" held to sell off items pillaged during the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), during which Fassini-Camossi had served.

One guest at the baron's house was Italian composer Giacomo Puccini. And a version of Mo Li Hua was even appropriated into Turandot, Puccini's 1926 opera, apparently the result of Fassini-Camossi playing the superior composer the 18th century song from his music box. Mo Li Hua was one of the only tunes that survived from pre-1930s China, and in various forms at that. By the time it made it into Puccini's opera, the song had gone through a number of revisions by "intellectuals who had a very specific and nationalistic mindset and wanted to create music for New China", Zhang says. In what he describes as a chaotic time, the melody briefly became the national anthem in 1896.

Shi Ba Mo, on the other hand, was virtually erased from official memory in China.

The appearance of Mo Li Hua in Puccini's unfinished final work helped solve the mystery surrounding the origins of the music featured in the composer's earlier opera Madama Butterfly. Set in Japan, Madama Butterfly had long been thought to contain Japanese songs. During an unexpected encounter with the music box at the Murtogh D. Guinness Collection of mechanical musical instruments in the Morris Museum in New Jersey, Sheppard discovered otherwise. Here he found that Mo Li Hua and Shi Ba Mo sounded undoubtedly similar to the "tinkling" notes in Puccini's Madama Butterfly. Bovet's thorough transcription helped confirm his suspicions.

"Other surviving Swiss music boxes from the period include these melodies," Sheppard wrote in a column for the Institute for Advanced Study. "However, the Guinness box crucially preserves its original tune sheet, listing the song titles in nonstandard transliteration and in Chinese characters. Thus, the Guinness box serves as something like a Rosetta Stone for this historical project."

And so Zhang's music box, formerly part of the Guinness collection, having planted a seed in Western musical culture, has returned to China and has been listed at about 3 million yuan ($478,000; 436,000 euros) at auction.

Zhang supposes he will hold on to the music box so it can be appreciated a little longer. He has two more on the way, but he has no idea what songs they have in them or what stories they hold.

As for future collectors or possessors of the Chinese music box, he guesses few of them will know much more about their history, but that should not stop a collector. After all, it did not stop Emperor Qianlong.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

|

Chinese-themed music boxes were made in small quantities in the Jura Valley of Switzerland toward the end of the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) for export to a few Chinese aristocrats. Provided to China Daily |

|

Both the inside and outside of these mechanical music boxes are a source of great beauty and happiness for collectors. Photos provided to China Daily |

(China Daily European Weekly 03/13/2015 page27)

Today's Top News

China likely to ease again if inflation falls: insider

Reproach for wrongful convictions

China's two universities make top 50

Astronauts return from space station

Italian court upholds Berlusconi's acquittal

UK companies seek new opportunities in China

CNR, CSR merger passes overseas antitrust scrutiny

Official urges Dalai Lama to forsake evil ways

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|