Aggrieved companies 'should go to court'

Updated: 2014-09-05 07:29

By Andrew Moody(China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

Expert says anti-monopoly law is modeled on EU legislation; not targeted at foreign firms

Wang Xiaoye, one of China's leading experts on anti-monopoly law, says foreign companies that feel wrongly accused of anti-competitive behavior need to take their cases to Chinese courts.

Chinese anti-trust investigators have descended on Microsoft, Mercedes, Audi, BMW and Japanese auto part makers in a wave of high-profile cases over recent weeks.

|

Wang Xiaoye says the competition law was vital for the transformation of the Chinese economy. Zou Hong / China Daily |

Most so far have been prepared to accept fines from the authorities, rather than to appeal their cases in the courts, and some have expressed fears privately that they will not get a fair hearing.

"If they feel confident that everything they have done is right and they have not violated the law then I do hope they bring their cases to the courts," she says.

"I think it is very important that for the law to operate properly these cases are tested in the courts. The law is new here and we need test cases."

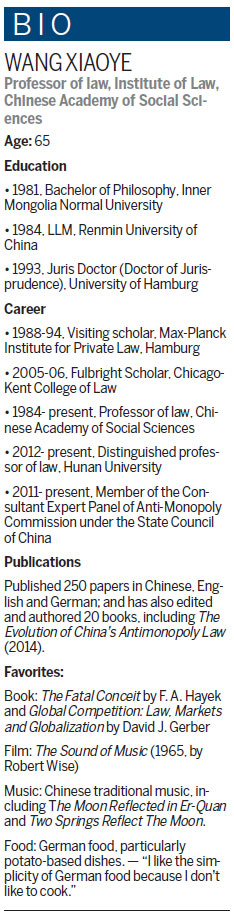

The 65-year-old professor of law at the Institute of Law at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing, is perhaps China's foremost expert on competition law.

She was involved in the drafting process of China's anti-trust laws, which came into force in 2008 and which companies are now falling foul of.

Since investigators descended on the headquarters of Mercedes in Shanghai last month, heralding a series of other probes, she has been at the center of a media frenzy.

She has been in demand from business TV channels, the Wall Street Journal and others seeking her perspective.

"There have been so many cases on monopoly law I am always doing interviews these days" she says.

Wang was speaking over pu'er tea in the relative retreat of her modest apartment near Panjiayuan flea market in Beijing's Chaoyang district, which she shares with her husband Tao Zhenghua, also a law professor, and her 91-year-old mother.

She says she has been frustrated in the past by foreign companies backing away from confrontation, particularly when the Chinese Ministry of Commerce blocked Coca-Cola's planned $2.4 billion (1.8 billion euros) takeover of Chinese juice maker Huiyuan in 2009.

"At the time I hoped very much it would go to court. Both the parties did not want to do this. If they had gone to court a decision could have been made as to whether the ministry was correct."

Foreign business organizations in China have expressed concern about recent moves. The European Chamber of Commerce in China said in a statement that "tactics are being used to impel companies to accept punishments and remedies without full hearings".

Wang, who is clearly passionate about her subject, is keen to get across that there is nothing alien or unique about Chinese competition law, which came into force six years ago.

She says it is largely modeled on European Union law and is less draconian than in other jurisdictions, particularly the United States, where offenders can go to jail and often do, since it is a violation of criminal law. Like in the EU, China's anti-monopoly law is just civil.

"People have this idea the Chinese authorities are operating in a vacuum. Yet the Chinese anti-monopoly agencies are often going to Europe and America and attending seminars and conferences. Chinese officials are always at the American Bar Association Antitrust Law spring conference."

She also says the recent "dawn raids" on company premises are also the same practices followed in other jurisdictions.

"If you told a company you were going at 2:30 pm tomorrow afternoon they might try and hide evidence of any anti-trust behavior. What has happened in China recently is normal practice everywhere," she says.

Wang was born in Zhangjiakou in Hebei province but was brought up in Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Her father worked for the local government and her mother was an auditor.

Just before she was about to graduate from high school, she was caught up in the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) and was sent to the countryside to work on a farm.

"I didn't complain. There were about 20 students like me all living, working and eating together. The farmers were very friendly toward us, although it was a very hard life."

Later, after working in a brick factory in the region's capital Hohhot, she was one of the first generation to go back to university, beginning a philosophy degree at Inner Mongolia Normal University at 30, when by then she already had two boys.

Her husband had studied law at the same university and she studied for law examinations soon after graduating before going to do a master's degree in law at Renmin University of China in Beijing.

It was a move to Germany in the late-1980s that led to her specializing in competition law when she did a doctorate at the University of Hamburg under the supervision of Ernst-Joachim Mestmacker, one of Europe's leading authorities in anti-trust law. She was there for six years and has since produced books and papers in German.

"Going to study in Germany was a key step in my life. It enabled me to understand the legal systems of developed market economies. It also allowed me to pioneer the study and research of anti-monopoly law in Chinese academic circles."

As a result she was the only legal academic involved in drafting China's anti-monopoly laws when the process began in 1994, although others subsequently become involved too.

"Competition law was vital for the transformation of the Chinese economy. When it was a planned economy, everyone and everything belonged to the government so these issues weren't relevant.

"Without laws, companies would just collude. It is far easier for a television manufacturer to agree the price of a television with a rival manufacturer than to compete with it but it would be against the interest of the consumer. It was therefore essential for China to have monopoly legislation in place."

Wang says the rise of China will be a game changer for how monopolies are policed globally.

In the EU, companies are often fined up to 10 percent of their global turnover for infringements.

In China the fines imposed tend to be only on China turnover or on the sales of a particular product line. The National Development and Reform Commission, one of China's main anti-monopoly regulators, fined 10 Japanese car part manufacturers, including Sumitomo Electric, 6 percent of their China revenues on Aug 20.

"You can't have a situation where a company is fined up to 10 percent of global revenues in every jurisdiction since there is only so much of their global turnover to go round," she says.

"I think the emergence of a large market like China will change how monopolies are controlled and other jurisdictions will begin to impose fines on revenues within their own areas."

Wang, who has made presentations on competition law before the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress on two occasions, denies any suggestion that the recent cases mean foreign companies are being specifically targeted by the Chinese authorities.

"Until recently most of the high-profile cases have only involved Chinese companies. Nationality is not important at all. What is at issue is the violation of monopoly law."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 09/05/2014 page32)

Today's Top News

NATO to offer tailored support to Ukraine

Babies bob about in water at US's first baby spa

News website staff face extortion probe

China's meeting on 13th five-yr plan

Number of visitors to China drops

Export of mooncakes on the rise

Putin outlines ceasefire plan for Ukraine crisis

China paves way for sports investors

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|