Uneasy partners who need each other

Updated: 2014-08-01 07:28

By Andrew Moody (China Daily Europe)

|

|||||||||||

|

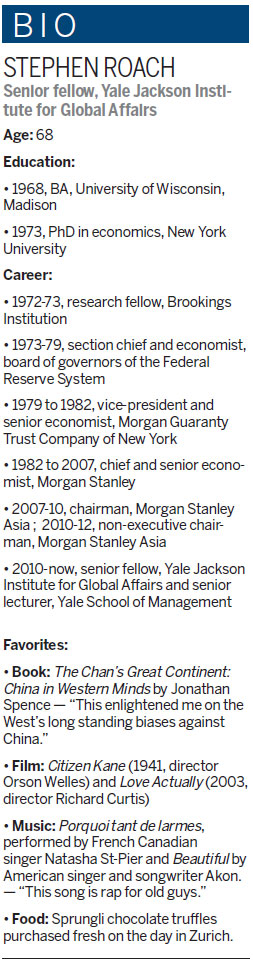

Stephen Roach, former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, says nobody in the Obama administration fully understands China. Hua Yu / For China Daily |

Of China and the US, only the former accepts need for change in relationship, says Roach

Stephen Roach says one of the problems with Sino-US relations is that nobody in the Obama administration fully understands China.

The former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia believes this makes the issues that arise between the world's two largest economies difficult to resolve.

"What concerns me is there is no real expert on China, its system, its economy and its people at high levels of the executive branch of the Obama administration," he says.

"Earlier administrations had Henry Kissinger and, although I am no fan of his, Hank Paulson (former US treasury secretary), also knew China very well."

Roach, 68, who is now senior fellow at the Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs at Yale University, was speaking in the Ritz-Carlton in Beijing after the launch of the Chinese edition of his latest book, Unbalanced: The Co-dependency of America and China, in which he puts Sino-US relations on the psychiatrist's couch.

"Well, I don't know. Maybe I am the first one to set himself up as a psychoanalyst of economies," he jokes.

He likens the relationship, however, to that of a bad marriage, where the two partners lose their individual identity and are subsumed within an often failing joint enterprise.

"Co-dependency is a term that comes from the study of human psychology where two individuals in a relationship become overly dependent on each other to provide them with a sense of who they are.

"These relationships are not sustainable. They create problems between those involved and in many cases lead to a break-up."

Few are as well qualified to make such judgments as Roach, who has high-level connections in both Beijing and Washington and has seen the relationship first hand in a 30-year career with one of America's leading investment banks.

He is close to former US secretary of state Hillary Clinton and financially backed her campaign to become the Democratic Party's presidential nominee in 2008. He believes if she were to stand again and become president, it could be good for Sino-US relations.

"She is a smart woman. She has certainly thought a lot about China. It is presumptuous to say that Hillary Clinton is going to be president next time. Who knows what is going to happen between now and then? I think she would certainly be better at drawing together a team of inside experts to grapple with China."

Roach, who was brought up in Beverly Hills which has given him a lifelong passion for movies, got to know China well himself in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis in 1997 when there were concerns its economy might be the next domino to fall.

"I was head of Morgan Stanley's highly-ranked global economic team. And I must tell you that despite our No 1 ranking, we had one of the worst forecasting records (in relation to the crisis). It was personally humiliating for me."

He challenged himself to visit China twice a month in the second half of 1997.

"It became clear to me that not only was China not going to succumb to the crisis but also that it would emerge as the new economic leader of Asia and play an important role in driving the global economy for years to come."

It was then also that he began analyzing the Sino-US economic relationship and its co-dependency, which he argues in the book dates back to 1978.

It was the year that Deng Xiaoping set China on its reform and opening-up course when, according to Roach, its economy was "on the brink of collapse".

Meanwhile, the United States economy was mired in "stagflation" and needed a new growth model.

"Out of necessity both countries came together and formed a marriage of convenience. The United States needed cheap Chinese goods to make it happen. China needed foreign consumption in order to become the ultimate production machine.

"Chinese savings then became a support for America's growth model which needed Chinese demand for its treasuries (US Treasury Bills)."

Roach says the problem with this co-dependency was that it was pushed "too hard for far too long" until cracks began to appear.

"Both economies started to feel the weight of imbalances and frictions that raised sustainability issues of their own."

He argues in the book that 2007 was the next pivotal year in the relationship.

It was Wen Jiabao, then Chinese premier, who warned the Chinese economy was "unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and ultimately unstable" in what has since been referred to as "The Four Uns".

"He was bold enough to make the criticism while the economy was strong and in surplus. It was also a pivotal year in the United States since in the second half we had the first manifestations of the sub-prime crisis that nearly brought the entire financial system to failure."

Roach says that 2013 was the third significant date in the relationship when it became clear that China had fully taken on board the dangers of co-dependency while the United States was still largely in denial.

He contrasts the whole series of economic rebalancing measures set out in the Party's Third Plenum last October against the political paralysis in the United States in its failure to agree a new federal budget.

"A month after the Third Plenum we shut our government down for 16 days. So of the two co-dependent partners, only one accepts the need for change."

This situation where only one partner to the relationship accepts the need to change is part of the "unbalanced" nature of the two country's relations that provides the title of Roach's book.

The author argues in the book that the relationships between the key individuals on both sides, particularly between former Federal Reserve Bank chairman Alan Greenspan and China's reforming premier Zhu Rongji and, more latterly, Wen and Greenspan's successor Ben Bernanke, have been intriguing. His book devotes a couple of chapters to this.

"Despite coming from different systems, the problems they had to grasp with were in many ways similar. They were also people who knew each other and therefore had an understanding of each other's issues."

One issue that has provided a distraction for policymakers has been the financial crisis.

Does Roach believe that the global economy is beginning to move away at last from the disaster that befell it six years ago?

"I think the problem is that we are moving so slowly that it still looms larger in the rear view mirror than we would like.

"The US is widely viewed as the engine of the developed world but it is not much of an engine if it can produce only zero growth, as it did in the first half of this year."

Roach is interested in the debate prompted by French economist Thomas Piketty's book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which he is one of the few to have read cover to cover, if the recent Amazon survey is to be believed.

"I like the book. It is perhaps too long and covers too much but there is a lot of valuable data and god insights that give you pause for thought.

"I think he perhaps views himself more as a challenge to the economic orthodoxy than he actually is."

As for China, which he has visited four times already this year, he is confident about the current economic reforms.

"Last year was the first time in modern Chinese history when the tertiary or service sector was larger than the secondary one," he says.

"Services require 30 percent more workers per unit of output than manufacturing so China can grow at 7 percent and no longer 10 percent to absorb all its labor. I think this is a very important shift in China's development."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily European Weekly 08/01/2014 page32)

Today's Top News

London hottest property for Chinese investors

Liberia shuts schools over Ebola

China's men no match for women?

Thai junta sets plan for fast rail links to China

Carnage at UN school as Israel pounds Gaza Strip

Abbas declares Gaza 'disaster area'

US House approves lawsuit against Obama

3 people killed, deputies wounded in NC shootout

Hot Topics

Lunar probe , China growth forecasts, Emission rules get tougher, China seen through 'colored lens', International board,

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|